The lights dim. The curtains open. A world that did not exist a moment ago is conjured into existence before our very eyes. Lives are storied into being. Hopes, desires, and doubts manifest through a bodied design in space and time. As audience members, we bear collective witness to these processes of “becoming.” For a short while, we can live vicariously through others–shifting, experimenting, transforming. Pondering possibilities. Imagining how we can “become” differently.

Whether a play, a musical, a theatrical performance, physical theatre, community theatre, visual theatre, applied theatre, or intermedial theatre; whether in a theatre building or a building site; whether at heritage site or crossing multiple sites; whether inviting active audience participation or activating the invisible barrier of a “fourth wall;” theatre compels us to think about how we can story ourselves in/and our world(s) differently. As much as it is a process of making meaning, it is also a process of unmaking meaning. In the space between making and unmaking, being and becoming, worlds of possibilities unfold.

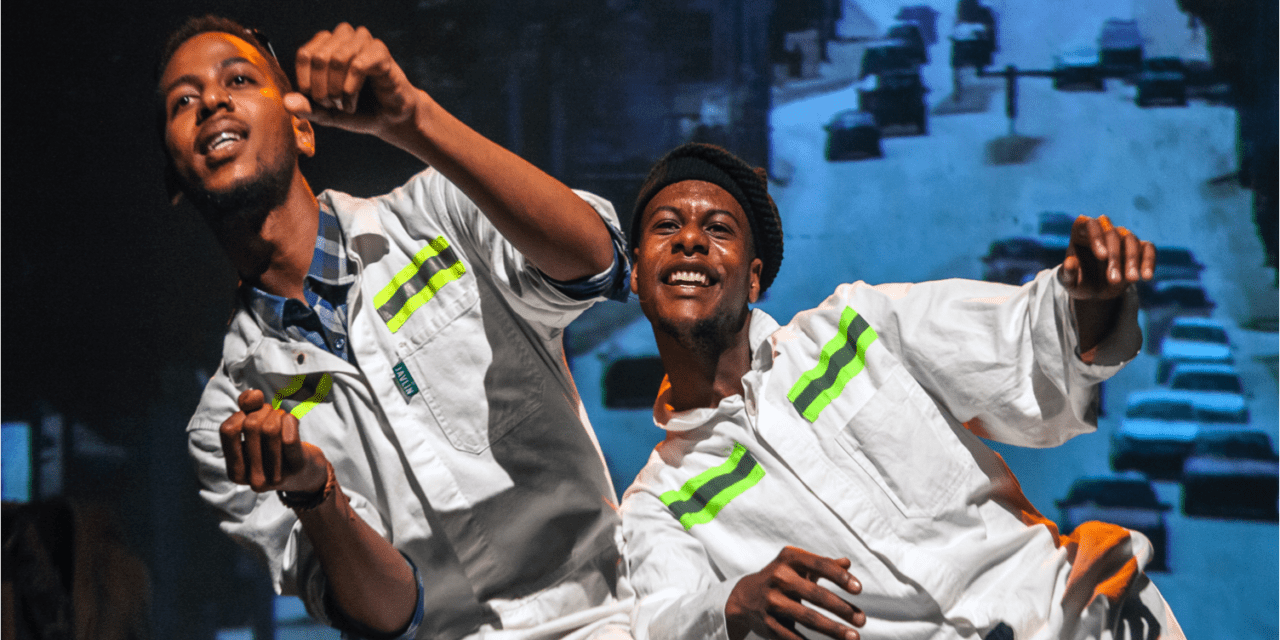

Chasing, choreographed by Nicola Haskins. Center: Chanel Muller and Mdu Nhlapo. Photo: Spiro Schoeman.

This holds for us human beings as much as for theatre. Theatre, as a performing art, is continuously shifting. As a performing art, it is often associated with staging plays or musicals. Yet, it has long transcended this same association through active interfaces with other live and performing arts, as well as through performative technologies. Not only do these interfaces question the parameters of theatre, the latter also brings into question the notions of liveness, immediacy, and relationality that are (were?) central to understandings of the nature of theatre. Concepts such as theatricality and performativity (whilst in themselves slippery) further extend notions of theatre (and performance) to a range of communicative processes, cultural and creative phenomena, as well as political encounters. What remains central through all these mutations, iterations, delineations and deliberations, are human experiences and behaviors. In a world of super-complexity that is ever-changing, we should perhaps be less concerned about the forms theatre may take, but rather about the purposes it may serve in exploring what it means to be human and how we can discover our own humanity through our interactions with others.

These ideas fuel World Theatre Day. Instituted in 1961 by the International Theatre Institute (ITI), it is celebrated annually on March 27. More than celebrating and promoting theatre in its varied forms across the globe, World Theatre Day has at its heart the ideal of theatre being central to a culture of peace. Each year, the ITI, invites a prominent figure in the broad domain of theatre to reflect on that exact theme. In 2018, the ITI made the decision to celebrate inclusivity and diversity by inviting five artists from each of the five UNESCO continents to author messages. Wèrê Wèrê Liking, from Côte d’Ivoire, represents Africa (read her message).

Barbe Bleue: A Story About Madness, directed by Gopala Davies. Center: Tina Redman and Cassius Davids. Photo: Gopala Davies.

Inasmuch as theatre holds potential for peacebuilding and resistance, it holds potential as a mechanism of hegemony and coercion. South African theatre is a prime example of both. Broadly speaking, the colonial context in South Africa (in particular form the late 1700’s onwards) saw to the development of a definite hierarchy of cultural and artistic discourses and practices that foregrounded the values, symbols, and perspectives of the dominant order and worked towards its advancement. This heritage, sidelining indigenous modes of theatre and performance and theatre in townships, formed the basis of the official South African theatre landscape into the 20th century. Protest theatre (emerging more vociferously as a genre in the late 1960’s) and theatre outside of mainstream spaces, harnessed theatre as a cultural and political weapon. Theatre in mainstream, government-funded spaces continued to affirm the storied ideas of power, dominance, and belonging–a toxic collision/collusion of nationalism, race, and class. There were, of course, notable exceptions. On the road to 1994, theatre continued to unmake historically dominant meanings related to its function and operations in South Africa. Theatre continued to imagine possibilities for new ways of relating and for negotiating new kinds of social contracts–and to ask us to join in these imaginings.

So strongly was the focus directed towards resistance to centuries of oppression, that the advent of democracy saw South African theatre at a momentary loss for words. What was imagined seemed to have manifested. Stories of apartheid, race, and liberation seemed to give way to stories of identity politics, women’s and gender rights, sexuality, HIV and AIDS, and reconciliation. The realities of our new democracy soon surfaced through the residue of colonialism and apartheid. In the face of continued injustices, racism, corruption and conflicts, theatre with renewed vigor, began to re-imagine the relationships between our histories, values, perceptions, and symbols. It started asking uncomfortable questions about how we position ourselves in relation to these. In doing so, it exposes what we are in the in the processes of our becoming. It reminds us that we have the capacity for compassion and compels us to imagine “how” we can “become” differently in the interests of social justice and responsible citizenship–in the interests of peace.

Theatre has a significant role in to play today negotiating pathways through the minefields of our current contexts. It has the potential to reveal, speak back to, and transform the ways in which we think about, and engage, with our contexts. Theatre offers a profoundly dialogic space in which to confront and navigate our differences, from which to build conceptual and emotional structures that facilitate the recognition of our shared humanity, the development of tolerance and communication, by which to create a more humane world. By witnessing how others story their lives and navigate their desires and doubts, theatre encourages us to unfold worlds of possibilities for ourselves and others. The repeated acts of witnessing that theatre encourage, allow us to make and unmake meanings and to access realizations that hide “in-between” this making and unmaking.

When your curtains open tomorrow morning, you can bring into existence a world that did not exist a moment ago – before our very eyes.

This article was first posted on www.up.ac.za/drama and reposted with full permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marié-Heleen Coetzee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.