Oliver Micevski (b. Skopje, Macedonia, 1980) is one of the most creative and intelligently perceptive Macedonian theatre directors and is the founder of Oliver Micevski’s Theatre Company / Budapest Contemporary Theatre. He has a BA in Theater Directing from the Faculty of Dramatic Arts, University Skopje, Macedonia, and a specialization in Ibsen at the Ibsen Center at the University of Oslo, Norway. Currently he is living and working in Budapest, Hungary. He is staging his theatre performances in European theatres – Skopje, Budapest, Cannes, Dublin and so forth. His most important theatre performances are Glass Menagerie, by Tennessee Williams; Vernissage, by Vaclav Havel; Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov; Edmond, by David Mamet; and Winter Solstice and Ant Street, by Roland Schimmelpfennig.

Ivanka Apostolova Baskar: Oliver, why did you decide to leave Macedonia? What kind of professional opportunities and challenges do you meet in Denmark, Norway and Hungary, and what possibilities for work and personal/professional development have you embraced in the domain of contemporary European theatre, away from Macedonia?

Oliver Micevski: At first, I didn’t want to leave Macedonia. I was quite happy there and was looking forward to contributing to Macedonian theatre and direct performances with actors from there. My master’s studies at the Center for Ibsen Studies at the University of Oslo should have been just a temporary getaway from Macedonia for the purpose of enriching my knowledge and obtaining deeper insight into the life and work of Henrik Ibsen, one of my favorite writers. But in the meantime, the artistic/theatrical scene in Macedonia went in the wrong direction. Suddenly, theatres were occupied by directors whose main quality was their connection to the government in power, first to the right-wing VMRO and then to the left-wing SDSM. I was neither willing nor interested in getting involved in their political games, so in the name of my artistic freedom I unfortunately never returned, and I began doing performances in a bit more civilized countries like Norway, Hungary, France, Denmark, and Germany.

I did a performance in Norway that got pretty positive feedback from the audience and the media alike, and it opened doors to further possibilities of working there. But somehow, with all the respect for the professionalism that I experienced in Norwegian theatre, I missed passion, a component I desperately need in order to create joyfully. Doing theatre there has certain aspects of industrial production. Yes, everything goes smoothly, no one is ever late for rehearsals. But . . . the magic was missing.

After Norway, I ended up in Budapest, Hungary, where I found this magic, established an English-language theatre and stayed for many years. It is exciting and rewarding to do theatre in Hungary, whose actors are among the best in Europe. It is no accident that Hungary has won so many Oscars, Golden Bears, Golden Lions, in recent years. The art sector there is made up of extremely talented people and, in a nutshell, Hungary is a quite fertile ground for doing theatre and art in general. And yes, Hungarians are crazy, very, very crazy, in some special, charming way. After having spent half a decade in Hungary, I felt the need to examine other horizons, and I did performances in France and Germany as well. It was good in France; however, the theatre scene is stuck in bureaucracy and you need to go a really long way to do theatre there. Luckily, I had full support from the city of Cannes and we did two fantastic performances there.

Based on my experience, Germany is the best place for theatre in Europe. Theatre in Germany is a real thing. Rehearsals are a matter of life and death. German actors see theatre as the most important thing in the world. I’m looking forward to my next performance in Germany!

IAB: Objectively speaking, what is your opinion of the contemporary Macedonian theatre scene with respect to the inner development of the next crucial sections: local playwriting, dramaturgy, inventive theatre directing methods, re-setting the education in drama and theatre, stage leading methods for actors/actresses, creating good festival strategies, initiating brave co-productions and theatre managing policies in the Republic of Macedonia?

OM: Macedonian theatre is in a state of clinical death. We must say this out loud and acknowledge it. Nothing important has happened in Macedonian theatre since the last century. Not a single Macedonian performance showed up at any of the important theatre festivals in the world: Edinburgh, Avignon . . . . It is pointless to talk about any awards. We don’t have any playwrights who are actual on theatre stages around Europe and the world. With a few exceptions of mostly local, Balkan exchanges, Macedonian actors are unknown in the wider scene. Broadway, West End, are just an unreachable dream. A deeper analysis is required to discover the reasons for this apocalyptic state. I guess the key issue is in the theatre education at our Faculty of Dramatic Arts and the private school ESRA. As our leading theatre scholar noted recently: Macedonian actors, directors etc. are educated for a theatre that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s enough to see who the heads of departments, professors, assistants in the Faculty of Dramatic Arts are: everything becomes immediately clear.

Many wrong steps have been taken in Macedonian theatre in recent years. Macedonian playwrights – both gone and living – were entirely ignored by local theatre leadership. Theatre directors of my generation were employed in theatres in Macedonia in order to be silenced and controlled, and it killed the fire in them, something I was sadly witnessing to. Now they are nearly unusable, vegetating and waiting for their monthly salary every first day of the month. Others were simply neglected because of their political incompatibility. As a result, we don’t see performances by Martin Kochovski (in my opinion, the best director of the younger generation in Macedonia); Ivan Popovski, the best director in Russia, hardly ever directs in Macedonia, and so on and so on . . .

Luckily, there are certain rays of light, of course. I primarily refer to the National Theatre Bitola, which managed to become immune, more or less, to changes of government and is still a leading force in Macedonian theatre thanks to the careful choices of directors working there. Their former leaders, Valentin Svetozarev and Blagoj Micevski, reached certain heights that were unknown for the rest of the theatres in Macedonia. I am afraid that their new leadership won’t be able to continue this progress over the long term because, as it seems to me, they are not autonomous and are not allowed to make independent decisions; they are instead executing the wishes of the current government. So, let’s see how capable they are of operating a theatre not pressured by politics.

IAB: In 2012 with several colleagues you founded the Theatre on the Roof, and in 2018 you transformed it into Oliver Micevski’s Theatre Company. You are also solo manager and house theatre director. What kind of theatre are you creating there, what kind of artistic necessity it is all about, and what kind of managing and program independence do you tend towards? In between, do you regularly collaborate with your Macedonian colleagues – actors/actresses, costume designers, set designers? In a certain manner, did you never end your relationship with Macedonian contemporary theatre?

OM: When I arrived in Budapest in 2012, there was a gap in the English theatre repertoire, which had a long tradition there before with the widely known Merlin Theatre. Together with a group of actors and some collaborators, we found a suitable venue on the rooftop of a building in the center of Budapest, so we founded Theatre on the Roof and began producing theatre performances in English. In Budapest, there are around 50 operating theatres, but none of them were offering English-language performances, with the exception of few improv theatre productions, and there was a huge demand for it because of the significant number of expats and international students. As a consequence, all our performances were fully attended, and we began to grow. After our building/roof was sold to an investor, we rebranded our theatre as Oliver Micevski’s Theatre Company, since my artistic language and approach had become a trademark of our work over the years. Recently, we founded an association besides Oliver Micevski’s Theatre Company called Budapest Contemporary Theatre, which serves as an umbrella platform for other independent companies in Budapest with a focus and interest in contemporary theatre.

I try to cooperate with Macedonian actors and stage designers wherever it is possible. With such collaborations, I fill up the emptiness in my soul created by the absence of my work in Macedonia. We had quite an exciting mutual working process with the Macedonian actress Sara Klimoska in the performances Hitler and Hitler and Winter Solstice, and purely enjoyable collaboration with the most renowned Macedonian contemporary multimedia artist, Zaneta Vangeli. We look forward to our future performance with the actress Natasa Petrovic in an upcoming leading role. It’s not easy to include Macedonians in the team, mostly because of distance and logistics, but I sincerely hope that this trend will continue and that I will still have the pleasure of doing a performance – at least partly – in my native language.

IAB: What was the first theatre performance that made Ms. Zaneta Vangeli (a Macedonian visual artist/set designer) your permanent artistic collaborator in visual dramaturgy (graphic design, costumes, set designs, theatre video)? What kind of collaborative, creative and mental chemistry is present and exchanged between the two of you? How do you see yourself collaborating with her?

OM: Zaneta Vangeli is a miracle. Probably the most refined pearl in the fine arts in Macedonia. I am honored to have her as a co-worker. We linked up during the preparations for the performance How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients, by Matei Visniec. Our plan was to do this performance in Drama Theatre in Skopje, but this project wasn’t suitable for Macedonia’s new government (former communists), and unfortunately, the performance never saw the light of day. Nevertheless, I invited her again to work on the stage/costume design for my next performance, Winter Solstice, by Roland Schimmelpfennig, in Cannes, France. It was a beautiful collaboration with artistically powerful results, so we continued to work together, on my next performance, Ant Street, too, and we plan to do more performances together in the future as well.

It was always a very smooth and creative process. We share similar systems of values. Our understanding of what is beautiful and what is not is pretty close as well. And, finally, we are both Christians, which makes our ideological path in life more or less the same and usually erupts in the shape of very potent artistic results.

IAB: How do Hungary and Denmark affect your sensibility as a human being and a theatre artist? Our own reality in everyday life and our surroundings – here and now – inevitably manifests the zeitgeist in this very moment of our lives and professions.

OM: The influence of Hungary, Denmark, Norway is inevitable, in both my private and my artistic lives. Luckily, Hungary shares many similarities with Macedonia, so I feel like Budapest is my second home. Also, my partner, Sara, is Hungarian, so I am kind of bound to accept Hungary, its traditions and way of life. Hungarians are masters of non-verbal communication, whereas they often fail in the verbal one. This is reflected in their theatre scene too. Hungarian verbal theatre is often outdated; there is not much worth seeing there, whereas in physical theatre, dance, ballet, they are masters onstage, probably among the best in the world. During my years of work in Hungary, I gained a lot of knowledge about physical theatre, and as time passes, my performances are inclined more and more towards body movements than towards spoken lines.

Norway and Denmark are a completely other reality where silence, simplicity and inner life play the main part. Given that they’re Protestant countries, the religious ideology of insisting on simplicity has shaped their understanding of life and art as well. Their architecture is rarely glamorous; their homes are super simple. The famous Nordic design (Ikea, H&M, Volvo, Skagen, etc.) and the movies of Lars Von Trier are identical examples of the Scandinavian way. This simplicity, minimalism, has affected the way I understand theatre and art of course, so minimalistic language is the most recognizable element of the theatre that I do now.

IAB: Why is minimalism part of your theatrical approach: what kind of freedom of visual-scenic-dramatic expressions does minimalism give you? How do you challenge the actors, and what do you expect from them? In between do you also lead workshops for professional actors, methodologically based on how they should act using the English language as their non-native language while acting in the English-speaking theatre performance? How do you challenge the audience, and what do you expect from the audience?

OM: Definitely, less is more. Furthermore, in the age we live in, people are overburdened with everyday attacks of all senses online, in TV, ads . . . which is why their attention can be caught more easily by minimalism. My performances work on a subliminal level. Usually, the audience is deeply affected, but they don’t know how it happened exactly, they can’t explain it rationally. When we work with actors and the other collaborators, we reach the final result through a process of condensation and purification. I worked on an adaptation of the novel Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov, in Budapest some years ago. We began with 500 pages of text of the original novel; we continued with 50 pages of adaptation; near the end, there were only a few pages of text left; and at the premier, we had no spoken words at all. Those 500 pages of the novel were still there somewhere, yet invisible.

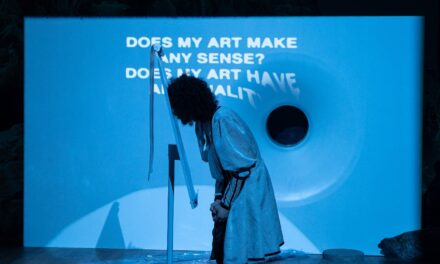

It was a similar case with the stage design for my latest performance, Ant Street, by Schimmelpfennig. With the stage and costume designer Zaneta Vangeli we began with grandiose ideas – flying horses; huge Castro, Che Guevara pictures; microphones – and slowly we began to reduce and sublimate, so at the end we arrived at the point where we agreed that one simple line, a rope, is enough for the entire performance. Anyway, the rope wasn’t comfortable for the actors, and it took all their energy and focus not to fall over, so a simple bench was our ultimate fix.

If we take a closer look at the most valuable films, plays, paintings or music of the past few years, nearly each of them was a minimalistic creation. I often see theatre performances around Europe. The best performances I have seen recently happened on an empty stage, no props, no costumes, no special effects . . . . We should have respect for the audience and their powers of imagination, and we should only give them hints or direction. Like this they are not lazy, and they can sense that they are co-workers in the process of creating. Perhaps this is the future of art. In art, as in life, things happen in a cyclical way. With postmodernism we have reached the peak of the cycle, so we will probably come closer and closer to the beginning, to the roots in both human and artistic terms.

IAB: As an artistic person, you are a creative ‘‘filter,’’ ‘‘converter,” ‘‘catharsist”; a ‘‘transformer’’ of ideas, impressions, concepts, scripts, plays . . . . How do you experience contemporary playwrights (Kostenko, Schimmelpfennig, Mamet) compared with the authors of classical modern works (Ibsen, T. Williams, Nabokov, Havel, etc.)? How do you recognize the play, the author; what kind of spiritual vibration is happening between you and the play/author and recognition for further theatre staging?

OM: It is very hard to find a good play and a good playwright nowadays. I assume that this is the main reason why theatres endlessly return to new stagings of old classics, and why we repeatedly see a new Shakespeare, Chekhov, Euripides, etc., in repertoires. Even in the history of theatre, the number of significant playwrights and plays was always very limited. Luckily, our age has given us numerous treasures in Roland Schimmelpfennig, David Mamet and Jon Fosse, who are still alive and rocking. My last performances are based on the plays of Schimmelpfennig, the most important living author in Europe (in the world, maybe) these days. He succeeds in bringing new ways in theatre, new forms, new ways of thinking that are suitable for the age we live in, very urban, often brutal, but also pretty poetic, gentle and genuine, of course. We developed a very nice relationship with Schimmelpfennig while I was working on his plays, so I believe that it’s a friendship that will grow and last.

I believe – as it usually happens – that when I am older, I will return to the classics, but for now, I am hungry for new plays, new writers, and I think this won’t change in the next years.

IAB: In this period with your new theatre performance, Ant Street, you are realizing a brilliantly conceptualized strategy for international premieres (tactics similar to film premiere formats) – a good festival strategy. Those are excellent directions/ways for opening up new possibilities, spreading European visibility and firming up international establishments. After Ant Street, what are your plans and projects for the second half of 2019 and for 2020?

OM: We just finished our tour with Ant Street. We had performances in Budapest, Cannes, Dublin . . . and as the cherry on top, Ant Street was selected as a part of CPH Stage, the most important theatre festival in Denmark, so we had a remarkable presentation in Copenhagen as our closer for this season.

My plans for 2019/2020 include a new performance by Schimmelpfennig in Budapest, one in Macedonia the next year, and my first show in the USA.

IAB: Thank you very much, dear Oliver Micevski, and good luck in your stage bravery.

—Skopje/Budapest, 2019

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.