What we really need in this capitalist, power-driven, exploitative, consumerist world, according to social critic David Korten, is… new stories.

Flippant? Not necessarily.

If “new stories” means alternative ways to envisage living out our lives, then the very future of humanity may depend on them. As Korten argues in his book The Great Turning (2006), new stories can re-orient us toward a different set of values that prioritize equality, responsibility, and social justice.

Where to find these new stories? Arguably not only (or even mostly) from technology or science, but “from the imaginative resources of a society often expressed in non-utilitarian ways.”

That is, from the arts.

Creating New Stories Through the Arts

We, the authors of this piece, are in Cambodia on an arts-based service-learning project, funded by the Australian Government through its New Colombo Plan. By supporting Australian undergraduates to travel and study in the Indo-Pacific, the Plan offers students the chance to deepen their insight into other cultures, lives, and worldviews.

With that in mind, our project moves beyond learning about Cambodian music, dance, and theatre in a purely artistic sense. It examines how the arts may be leveraged for social improvement, in Cambodia and beyond.

In particular, it explores the capacity of the arts and artists to spawn “new stories”: social, cultural and political alternatives that move us closer to a world of social justice and equality.

The Arts as Pathways to Healing

One morning, we visited choreographer, director, dancer, and teacher Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and her group, the Sophiline Arts Ensemble, at their outdoor rehearsal space in Kandal province.

Through classical and contemporary dance, Shapiro and her ensemble explore issues of social relevance to their homeland and beyond.

One work in their repertoire is the dance-drama A Bend In The River, a collaboration between Shapiro and composer Him Sophy. The work retells an old folktale about a young girl, Kaley, who finds her family eaten by a crocodile and seeks to avenge them.

Kaley’s tale of coping with injustice resonated personally with Shapiro, whose father and two brothers were among the 1.7 million who died during the Khmer Rouge regime.

For composer Sophy too, the performing arts represent pathways to personal and social healing. His latest work-in-progress, A Requiem for Cambodia, addresses the trauma of the genocide, four decades after Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge.

Giving a Voice to the Oppressed

In contemporary Cambodia, where injustices and inequalities are still commonplace, the disadvantaged and disempowered often lack a voice. In addition to their role in personal and social healing, the performing arts offer a legitimate yet powerful way to break silences.

Every week at the National Museum in Phnom Penh, young performers of the traditional theatre form Yike recount the tale of Mak Therng – a farmer whose wife is abducted by the king’s son.

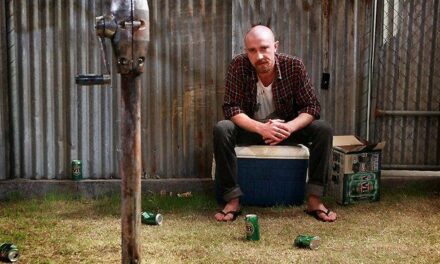

A scene from the Yike opera, Mak Therng, produced by Cambodian Living Arts. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. Catherine Grant, June 26, 2015, CC BY-NC-SA

In a country where corruption is rife and democracy a fluid concept, the work’s themes of power, authority, fairness, and justice are sensitive ones.

Most importantly, in the time-honored version of this old folk tale, the king defends the actions of his son. But in the present-day iteration, director Uy Ladavan chooses to discard the ending she learned more than 40 years ago. In her new story, the king sides with the farmer in his quest for justice.

Artistically, the difference is minor.

Socially, it is momentous: it offers a new vision for Cambodia, a vision wherein the vulnerable and disadvantaged feel able to stand up for their rights, and those with power assume fair responsibility for their actions.

Mak Therng bemoans the abduction of his wife. Scene from the Yike opera Mak Therng, produced by Cambodian Living Arts. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. Catherine Grant, June 26, 2015

When the philosopher Martha Nussbaum argued, in 2010, that the arts promote imagination, dialogue, ethical perspectives and “a notion of citizenship that goes far beyond simply voting in elections”, she surely was referring to the likes of this.

Social Change Through the Performing Arts

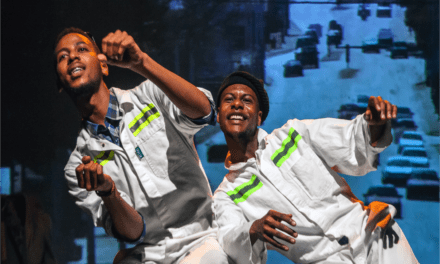

In Siem Riep, we met the New Cambodian Artists, an energetic group of female dancers aged 18 to 25 who explore Khmer classical dance in contemporary ways. In a country where gender disparity and gender-based violence are rife, the group both advocates for, and embodies female empowerment. The boundaries these young women are pushing are not only artistic but also decidedly social and political.

The New Cambodian Artists in rehearsal. Siem Riep, Cambodia. Left to right: Son Srey Nith, Khon Srey Nuch, Kong Seng Va. Matthew Harper, June 27, 2015

In many disrupted, disadvantaged, and disaffected places and situations around the globe – including Cambodia, but also Indigenous Australia, where the effects of Western colonization have lead to the massive loss of cultural practices – people are engaging in the process of rebuilding and re-imagining their present and future lives.

In this pursuit, the performing arts achieve far more than their often-cited utilitarian functions – developing transferable skills, building community capacity, generating income through tourism.

The performing arts also help us envisage new realities. They offer alternatives to the very way we live our lives. They empower disadvantaged and marginalized young people, who “discover that they, in fact, have talent, skills, imagination and the ability to influence their worlds through their artistic productions.”

By disrupting old stories and generating new ones, the performing arts help us transcend social, economic and political limits. As one scholar, John Clammer, has argued, it is through the arts that “the re-enchantment of the world might take place.”

From our vantage point in Cambodia, a country of vast challenges and equally vast possibilities, it is not difficult to see how this could be so.

This article first appeared on The Conversation on July 12, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Catherine Grant and Matthew Harper.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.