Australian theatre-maker, Olivia Satchell, explores the subjectivity of risk, and how artists frame their understanding of this concept in relation to their work. Is it possible that the artist’s personal conception of risk has no value for an audience?

The current celebration of risk in theatre is misdirected.

In Australia, in recent years, there has been a significant creep of “risk” into the marketing jargon of performance. This is most evident in our more conservative main-stage companies, who herald the presence of independent (dare I say experimental or avant-garde) theatre-makers in a season by promoting their position on the “cutting edge”. It is also evident in the attitude of these companies towards new work, the risk of which is bankrolled by the programming of canonical texts.

But what do we mean when we talk about this risk?

This question was the starting point for a project I helped run throughout 2014 with Somersault Theatre Company. We received Australia Council for the Arts funding to create The Risk Factory, a program that worked with playwrights to use risk as a starting point in developing new work. Alongside this program, I spent the year interviewing Sydney-based artists about how they encountered risk in their own practice.

My interest in this subject stemmed from an instinct that risk is inherently subjective. It is a word that we believe we understand in general terms, which then mutates upon close inspection.

My personal understanding of risk is informed by my socioeconomic background, my nationality, my ethnicity, my occupation, my sexuality, and my gender. It must necessarily be different for every person because it is informed by these individual differences.

There are, however, generalities that can be made within these categories of identification. For example, every individual that identifies as a minority may face the risk of emotional, physical, or spiritual persecution.

Some more specific examples within these categories were brought to light in an anonymous online survey that I conducted. The most common response to ‘What is risk?’ was “love,” which was closely followed by moving overseas with no money, a physical activity’s potential for bodily harm, and the revelation of either an individual’s mental illness or their sexuality.

All of these understandings of risk are concerned with self-preservation. Is this concern applicable in theatre?

Belarus Free Theatre

A group for which it does seem important is the Belarus Free Theatre. Nikolai Khalezin and Natalia Koliada founded this company in 2005 to resist the authoritarian regime brought in with President Alexander Lukashenka. Their first production, Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis, focused on themes of depression and suicide, which were both taboos in state-controlled art. Free Theatre performances were held in private apartments, basements, and sometimes in the woods, and were constantly relocated due to the risk of police harassment. Their artists faced mass arrests, and Khalezin was forced into hiding in 2010. The risk of their art is most aptly summarised in Koliada’s Twitter biography:

“Founding Artistic Director of Belarus Free Theatre. Smuggled out from Belarus, the last dictatorship in Europe. London became a second home.”

This is a far cry from the conditions in which Australian theatre exists. We have ongoing issues with the tokenism of reconciliation and the reality of living conditions for indigenous Australians. Racism is vitriolic and rife, sometimes breaking out in sectarian clashes and mob violence. Our treatment of refugees is a source of collective shame. Art is not embraced or even wanted, by the majority, and the perniciousness of American surveillance is slowly encroaching on our shores.

But despite these issues, and our bubbling discontent at the incompetence of our politicians, we ultimately live in a democracy. Free speech is the norm.

What, then, can be risky about our theatre?

There is, of course, the potential for a critical and/or popular backlash in response to the portrayal of the issues that I have just outlined. One director spoke of the difficulty he experienced in predicting how the community would react to the portrayal of indigenous issues onstage. Another director, James Dalton, spoke of both his trepidation and commitment to Fregmonto Stokes’ Kill the PM, which was about four friends waiting in a dilapidated building in Sydney to assassinate the Prime Minister of Australia. This production was geared towards the gap between the ideal and the reality of democracy, which had significant implications for the steadily growing presence of government surveillance in our country.

These risks are concerned with socio-political content. What of stylistic elements?

“My Name is Truda Vitz”

A clue to this may be found if we return to the subjectivity of risk. This is the same for artists just as it is for everyone, but the key may be found in how artists frame their understanding of this concept in relation to their work. I can illustrate this best by giving an example from my own practice. Last year I performed in My Name is Truda Vitz, which was a solo work that I had written about my grandmother’s escape from Nazi persecution as a teenage girl. I have a terrible phobia about being onstage but was interested in performatively embodying the ripple effects of inter-generational trauma. The risk for me, here, was in the presentation of this work. However, if an actor had performed in my place the risk for them may well have come from a different source.

Importantly, it was unnecessary for the audience to be aware of the risk I was taking to encounter the work. My fear added nothing to the product.

Is it possible that the artist’s personal conception of risk has no value for an audience? What risk do we refer to then when we applaud it?

Let us return to the risks associated with producing new work. Griffin Theatre Company is the only main-stage producer of exclusively new Australian plays in the country. However, in recent years they have taken to programming a classic Australian play in each season. In the course of my interviews, it was suggested to me that this was a financial strategy to offset the potential loss they might face in producing more “cutting edge” new work.

What is the difference between these two commodities (the old and the new)?

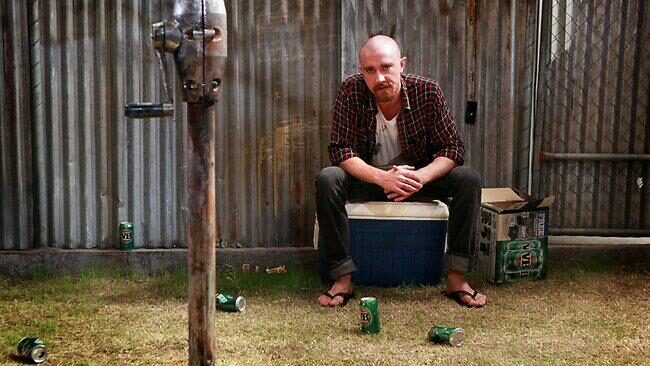

Griffin Theatre’s The Boys.

I believe the difference is that we know each edge of a classic text. We program a David Williamson, or an Arthur Miller or a Shakespeare or a modern adaptation of an ancient Greek because they are tried and true. We know they satisfy.

The edges, “cutting” or otherwise, of a new work are what we don’t know.

This brings us to the heart of the matter: our fear of the unknown and our fear of failure.

That these go hand-in-hand is illustrated by the belief that programming a known entity such as a canonical text will increase the chance of both critical and economic success.

This fits into the imperative of many main-stage companies, which is to achieve both stability and growth. The ideal is to create an identifiable aesthetic that is developed season by season, and which is sustained by an ever-increasing subscriber base. The threat posed by a new work, then, is understandable. Will you astound people more than you drive them away? Better to produce an old text in a new(ish) way than a new text that is a critical and/or popular failure, and which threatens the identity of your company.

A useful way to understand this conundrum is what Dalton referred to as the “tension of eyes.” This is the idea that greater exposure leads to an increased vulnerability to criticism.

This tension is as relevant for individual artists as it is for companies. We are addicted to narrative and will always read an individual play (or performance product) into an artist or company’s general aesthetic. This is inherent in our conception of a ‘body of work’. We look for identifying patterns to distinguish an individual from others in the same theatre ecosystem. The result of this is that there must always be a consideration of whether the risk you take will be read as a black spot in your body of work. What are you as an artist willing to potentially sacrifice?

Ultimately, the risk of failure is bracketed by the reality that “it’s just theatre.” Although artists might always be financially vulnerable and relegated to the professional fringe, the relative good fortune that we experience here in Australia – free speech, free healthcare, and a democratic government – should not be underestimated.

If Koliada and Khalezin are willing to risk their lives to make theatre, then surely it is our responsibility as artists to pursue and celebrate the unknown.

This was touched on by several figureheads in Sydney theatre. Anthea Williams, Literary Manager of Belvoir St Theatre, spoke of the importance of failing big and of the “death of a lukewarm reaction”. Tim Roseman, Artistic Director of Playwriting Australia and mentor for Somersault’s project, spoke of the imperative of exploring the unknown when expanding an audience’s “horizon of expectation.”

Playwright Suzie Miller

That this involves risk is evident in the media backlash experienced by playwright Suzie Miller for Transparency. Premiering at Ransom Theatre in Belfast in 2009, this work was about a child killer starting a new life after years in juvenile detention. A Sydney Morning Herald article from the same year took note of the accusations of mockery that Miller received from Denise Fergus, the mother of the murdered toddler, James Bugler. In response, Miller stated that the play was “neither pro-offender nor pro-victim” but instead designed to “find answers to difficult questions about what happens to children who commit terrible crimes.” When I spoke to Suzie she spoke of the need to start from a “position of openness” in her work and of her desire to write characters “in all their complexity” in order to show how they’ve become what they are. Tellingly, she was awarded the Kit Denton Fellowship for courageous writing in 2008 for this work.

I’ve come to the conclusion that one problem we experience as artists is how we frame our understanding of risk. More often than not we conflate it with the possibility of failure. The problem with this is that it locates our attention between ourselves and our work. What can I not do? What is too much of a risk for me because I do not believe I can pull it off? This is where we chance on solipsism. Instead, our focus should be turned outwards and located between our work and our audience. What is our work asking of the audience that they have not encountered before? How is it challenging them to lift their eyes beyond what they know?

Eugenio Barba writes in his introduction to Burning the House about the “impulses” which have collected together into his own unique method of theatre-making.

“These impulses were the rope which I grabbed to prevent myself from falling into an abyss of insanity. I gave names to these impulses. At times they became words which inflamed my imagination. I was a trapeze artist who oscillated in the air. I imposed a sense and rigor on this movement and I called it theatre. I didn’t dare to call it a circus. There the trapeze artist risks his life. In theatre, only my vanity was at stake.”

Olivia Satchell is a theatre-maker dedicated to developing and producing new Australian work. Her credits include Antigone (SUDS), Transformer by Jessica Redenbach (Griffin Theatre Company; Festival of New Writing), Heart Dot Com (multi-playwright project; Tap Gallery), Come and Join Me by Ellana Costa (Performance Space; Carriageworks), her one-woman show My Name is Truda Vitz (Somersault Theatre Company; Tap Gallery), and Twelfth Night (SCEGGS Darlinghurst). Satchell co-founded Somersault Theatre Company in 2013 and is undertaking her Masters of Directing for Performance at the Victorian College of the Arts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by The Theatre Times.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.