Polish stage director on his version of Dallapiccola’s Volo di notte and Il Prigioniero at the Colón.

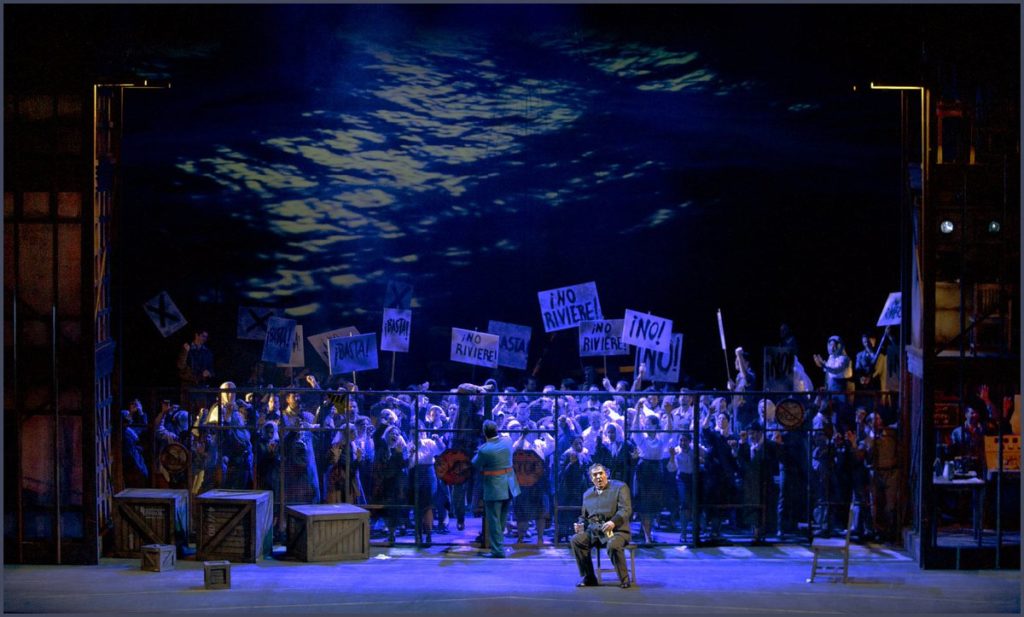

Last Fall, the Colón presented a Luigi Dallapiccola diptych including Volo di notte, based on Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Vol de nuit about doomed commercial night flights based at an Argentine airport in the 1930s, and Il Prigioniero, based on Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Torture by Hope. Polish stage director Michal Znaniecki took Dallapiccola’s critique of fascism and gave it a local twist, employing choreography and flying dancers as metaphors for the infamous angels of death of the Argentine military dictatorship.

In an interview with the Herald, Znaniecki spoke about his relationship with Argentine audiences, the globalization of productions nowadays and the meaning of freedom in any moment of time or any country.

You like to say that the viewer is not a monster that must be fought, but someone that it is necessary to conquer.

It’s always a pleasure to work for the audience, in and out of the subscription series, having the audience wanting to come, wanting to see and wanting to know. In Argentina, it’s very easy for me to delve into intellectual challenges about my connection and inspiration because I know that the audience will “read” it. I work in different theatres, different cultures — let’s say a production in Tel Aviv, in Warsaw and in Spain — so I have to think in terms of globalization on the stage just to come up with a different, easier way of communication. I trust Argentine audiences, they are very smart and they want to discover things. It’s like working with the Colón choir, we have this feeling that we know and trust each other, which is the most important thing.

The work you do is not a mass product though, to put it in terms of globalization. Considering how subjective art is, what do you take from the audience’s feedback in so many different cultures?

I’m an ex-assistant of maestro Umberto Eco, my professor from Bologna University, so of course, the opera aperta (open work) means the performance, the show begins in the head of the audience so I trust that they follow because they will build it based on what I deliver. So I always think what kind of knowledge, what kind of experiences and traditions my audience has. Even here, in Volo di notte o Il Prigioniero, I’m telling a Polish story about dictatorship, about torture and prisoners that I had in my family in Poland. Even if may seem far removed from the reality here, the Argentine artists working with me have told me, “No, this is our story.” So I’m just finding the way to relate the story onstage with the history of Argentine people. Working on this, I draw inspiration from my experience during Communism, all the oppression of my country because that is my experience but we are translating it into Argentine dictatorship times.

Do you want something to engage in the universal or the topical side of a work? Both these operas have transcended time.

It’s not that I want to personalize the operas. Volo di notte is set in Argentina but Il Prigioniero is a universal story that can occur anywhere. It’s the story of no freedom in every country, it can be Franco in Spain, it can be Stalin, Hitler or the Argentine junta. However, I would like to touch the history of Argentine audience. I want these works to hit home with every kind of viewer.

You say you’ve based this staging on your experience with Poland’s history. How do you bring that to the here and now?

My prisoner here is rather a political prisoner of a crazy situation of inflicted suffering, caught in a perpetual hell of torture and hope while the guards concoct this game of perversion letting him believe he stands a chance. I lost my two grandfathers in prison in the 1960s so this opera is very close to home and I’m happy that it can be read here as an experience that the audience can understand. Talking about yourself is easier but the audience must understand.

So you’re staging two 20th-century operas which touch on the horrors of fascism, you bring in communism and now we see the Argentine audience can filter it through its experience with the military dictatorship. Were you going for a multilayered work?

The amazing thing is that the libretto for Volo di notte is very existentialist and the opera is very strong musically, with big orchestration, reflecting the psychological turmoil to the point of a political manifest as the story of one man sacrificing the life of his workers. The music is spectacular, not at all small, every movement transcends, almost like saying this is not about one man, it’s about humanity. Il Prigioniero is obviously linked to dictatorships and you can set it in Mussolini’s time or in any time and place. It’s always about human beings and power, about how can they manipulate us. Which they can do even in times of peace.

Which should make it a more haunting discovery.

You know, it’s always surprising when you work and discover how current and real it feels in every country. Is this freedom we have now — because we have the money to go to the Colón Theatre and dine at good restaurants — is this really freedom? Every country and culture today can have they moment of “Oh my god!” I’m not trying to say that we live in globalization or a dictatorship of sorts, I’m just taking Dallapiccola up on his question: “Is this freedom we have now or are we already so manipulated by the powers that be and the media?” In the show, we use monitors and cameras to suggest that they are spying us all the time, like Orwell’s Big Brother.

You’re including choreography with acrobatics on stage.

The idea was to find the abstraction in the production so I could put the soldiers and police in a realistic way and talk about the angels of death, the angels of every dictatorship, of every historic situation. So we’ve added ballet dancers and acrobats hovering over the sets and the story. The idea was to bring out the abstraction in every dictatorship, except they’re flying, in a metaphor that can be easily understood.

This interview was originally posted on BuenosAiresHerald.com Reposted with permission. To read original interview, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by The Theatre Times.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.