In the 1950s, the National School of Drama was set up in India as a cultural organization entrusted with the task of preserving by means of showcasing and engaging in research in indigenous forms of Indian theatre. This move by the government betrays the need that was felt to prevent folk forms in drama from fading out. The threats that were perceived against these indigenous forms were from two directions. One was the result of the entry of Western forms like Realism, and the popularity of the proscenium theatre on the Indian stage. Against these Western forms, folk forms of drama appeared unrefined and technically limited. Moreover, in the present times, it is not difficult to see how the ‘cultural logic of late Capitalism’ is appropriating all local traditions in a Metanarrative of global culture. In India, this has become a trend where the only representation one sees of folk forms is in Bollywood cinema, which is also rare. Whether it’s the opening lines of the film Mangal Pandey sung in the Alha style, or Shyam Benegal’s Welcome to Sajjanpur that bases its plot on the premise of the bidesia story, people watching these films do not know enough about folk forms to be able to identify them. The other direction was that of the margi (Classical) against the desi (Folk). In the wake of National Revivalist theatre before and just after Independence, Sanskrit theatre was

In the wake of National Revivalist theatre before and just after Independence, Sanskrit theatre was recognized as being representative of Indian theatre, as a result of which many other theatrical forms and styles were forgotten. When A.K.Ramanujan (Ramanujan: 6-7): in totalks of the Sanskrit tradition in literature as being pan-Indian and folk traditions as being localized, he is giving into a setting up of a hierarchical structure in criticism that, in his own terms, distinguishes between the ‘Great’ and ‘Little’ traditions in India. In the context of theatre, this argument becomes even more problematic because unlike literature (kavya), drama (natya) is based on performance and as a form it derives its life force from a web of relationships between the written word, gestures, nat’s body and music. It is difficult, if not impossible to identify a pan-Indian theatrical form or style, because with every few miles, rhythms, tones, cultural signifiers change and they change theatre along with them. If one looks at folk forms like Baul, Tamasha, Dashavatar, Nautanki, Lavani etc, it is easy to notice that these forms do not adhere to all the principles of the Natyashastra, the seminal treatise on drama composed by Bharatamuni. There is partial acceptance, partial variation at times. Therefore, one can only imagine the rich variety of folk forms that exist in Indian theatre, ‘Bidesia’ being one of them.

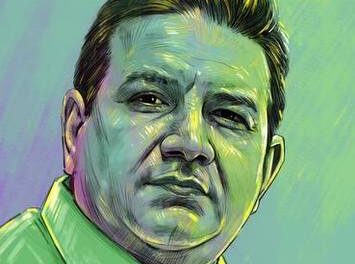

In modern Indian theatre, Bhikari Thakur (1887-1971), referred to as the ‘Shakespeare of Bhojpuri’ by Dr. Manoranjan Prasad Sinha for his immense popularity amongst his folk, is a major playwright and artist. He has to his credit twenty-nine books, consisting of famous plays like Bidesia, Beti-Viyog, Vidhva-Vilap, Ganga-Snan, Gabarghichor and Kaliyug- Prem, and songs and kirtans like Shiv-Vivah, Ramlila-Gaan, Budhshala ke Beyan, Shanka Samadhan etc. Thakur was born in Kutubpur in Saran district in Bihar to Shivakali Devi and Dalsingar Thakur. Belonging to a low caste (nayi or barber) and having lived his life in very poor conditions, Bhikari Thakur was illiterate but taught himself to read and memorize Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas whom he considered his literary guru. His theatrical style known as ‘Bidesia’, after his most famous play of the same title, uses folk idioms, music, and elements from folk forms like tamasha and nautanki. Bhikari Thakur, in his travels across Assam and Bengal, had been exposed to jatra, which, along with Ramlila and Raslila influence his dramatic form. In his plays, female parts were played by male actors, who wore false long hair and ornamented them. It has also been noted that Thakur was familiar with the popular Parsi theatre of that time. The stage in his theatre was always an improvised raised platform, with the audience sitting on all three sides. The lighting used consisted of locally available options like lalten and dhibri.

To a certain extent, his theatre also imbibes some principles of classical Sanskrit drama. For instance, every play begins with mangalacharan, which is considered essential to the beginning of anything auspicious. In the nandi, which comes at the opening of a Sanskrit play, prayers are dedicated to Ganpati and Saraswati, asking for blessings for the performance. In Sanskrit drama, the space of performance of natak is considered sacred and therefore prayers, elaborate gestures and the formal beginning of the drama. There is also the sutradhar, the narrator, a part that was often played by Thakur himself in many of his plays. In Bidesia, in the Prastavana or Prologue, there is a reference to the play as possessing a mixed form that is of folk and classical. In the nandi, which is replaced by the mangalacharan, prayers are offered, first in Sanskrit, then in bhajans and songs by the sutradhar. After the prayers, the play is introduced in its theme, drawing examples and parallels from Hindu mythology, the story of Ram being the most popular. The prologue focuses on the predicament of the wife, whose agony of separation is dealt with in detail and with sensitivity.

The play Bidesia has primarily five characters, namely Bidesi, Batohi, Sundari, Randi, and Devar. The play is named after the central character Bidesi, who represents the predicament of young village men, who are forced to migrate to foreign lands (bidesh) in search for better living. His wife, Sundari is a simple woman, devoted to her husband. When in bidesh, her husband meets and falls in love with another woman, typified as ‘randi’, referring to her socially unacceptable position. Batohi is a wise man of the village, one who is wont to traveling frequently, and so is a man of the world. He is the messenger who goes to town carrying the wife’s message. Another character is referred to as ‘devar’, a young man, who, in the absence of Sundari’s husband, tries to come close to her and exploit her sexually. Besides, there are other minor characters like Bidesi’s friend, samaji, and some village people. The Sutradhar comes after the mangalacharan, and introduces the prologue, which is mainly in song mode. The songs are set to folk rhythms like jatsari, lorikayan, sorathi, and verse forms like kabitta and chaubola.

The characters in Bidesia are types representing the general rather than the particular. The young man Bidesi stands for all those young men, who are left with no choices but to try their fortune in unknown places like Assam and Bengal. In this play, Bidesi goes to Kolkata, on the suggestions of his friends and based mainly on the promises of opportunities and better prospects there. His wife is a type for all women who are left behind in villages, sacrificing their marital life for the betterment of their family. Bhikari Thakur was very sensitive to the issues of women in their mostly passive and marginalized conditions as wives, daughters, and widows. In this play, through the innocent and sincere character of Sundari, Thakur has drawn attention to the helpless positions of such women who are financially dependent on men and therefore outside the domain of decision making. Also, these women are forced to part with their husbands so that the solitude and depression resulting from this separation become the reality they live with every day. Further, in the absence of their life partners, and in moments of sexual desire, the men find options of engaging in relations with other women.

Though these men are able to recreate a parallel life for themselves in towns, it is their wives who pine for a life that has been destroyed, back in their villages. While Thakur is sympathetic to the conditions of these women, he is also sensitive to the awkward position of the other women in the life of these men. The new woman he lives with is also sincere in her relationship and her position becomes compromised once the man returns to his village. In the end, Thakur offers a solution, which, though not very liberal, is in keeping with his vision of happy, extended families. In the end, the man and the two women along with the children he has in Kolkata, live together as a complete family. From a feminist ideological point of view, this may appear to be a convenient solution to a serious problem. However, one has to look at the immediate coordinates of time and place to understand that what Thakur is offering is a practical solution to a problem that is rampant in that region.

Thakur, in his plays, raised pertinent topical as well as universal issues concerning women, low-caste people and poor people living in villages. Bidesia draws attention to the problem of migration and its effects on the women who are left behind, Beti viyog, to the practice of mismatched marriages which are executed between young girls and aged men in exchange of money for the girl’s family, and Vidhva-Vilap to the helpless position of widows in their families.

The appeal of folk drama lies in its spontaneity, energy and the relevance of its subject matter. In Indian theatre, there is a rich variety of folk forms, undocumented and unexplored, which can make drama more meaningful in connecting with people. With the efforts of individuals like Habib Tanvir, and Ratan Thiyam, elements of regional performance traditions have been brought into the mainstream in their original flavour and strength. However, more needs to be done with regards to such forms like Bidesia in Bihar or Alha in Bundelkhand (U.P), which are still popular amongst people living there and have also traveled with the migrants to such distant places as the Fiji islands, Mauritius, Kenya, Uganda, Trinidad, British Guyana and to nearer countries like Nepal and Singapore. Bhojpuri is a language that spreads across Bihar, as well as parts of Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Amongst the regional languages spoken in North India, Bhojpuri has a wide reach. It is also spoken, written and read in fourteen countries across the world (Yadav: 3). Bhikari Thakur’s theatre spans the period from pre-independence, when he traveled to Bengal and was influence by the intellectual currents there, to post-independence Nehruvian India, which was still dealing with issues of caste, social ills and communal prejudices. His theatre is important for his vision of a progressive and peaceful society, where every individual has the right to live with self respect, his depiction of the problems of his folk, and for the mass appeal and reach of his plays, kirtans and songs. As a spontaneous performer-singer, dancer and actor, Thakur acted in his own plays and directed his productions. He was not just an immensely popular playwright, but an entertaining performer who constantly improvised in his productions. In folk theatre, with its flexible structure that provides space for improvisation and experimentation, the text is constantly rewritten in the hands of actors and musicians. The play ‘Bidesia’ is the most well known, and in its range of thematic concerns and depth of emotional sensitivity, probably the best representative of Thakur’s oeuvre. For the migrant people, not just from Bihar, but from all those underdeveloped parts of India, who leave their homelands and place their family relations at stake, this play would appear as a personal text of tribulations and trials they and their family members face every day, and speak to them in a language of emotions that is not dependent on translations.

Bhikari Thakur’s theatre spans the period from pre-independence, when he travelled to Bengal and was influenced by the intellectual currents there, to post-independence Nehruvian India, which was still dealing with issues of caste, social ills and communal prejudices. His theatre is important for his vision of a progressive and peaceful society, where every individual has the right to live with self-respect, his depiction of the problems of his folk, and for the mass appeal and reach of his plays, kirtans and songs. As a spontaneous performer-singer, dancer and actor, Thakur acted in his own plays and directed his productions. He was not just an immensely popular playwright, but an entertaining performer who constantly improvised in his productions. In folk theatre, with its flexible structure that provides space for improvisation and experimentation, the text is constantly rewritten in the hands of actors and musicians. The play ‘Bidesia’ is the most well known, and in its range of thematic concerns and depth of emotional sensitivity, probably the best representative of Thakur’s oeuvre. For the migrant people, not just from Bihar, but from all those underdeveloped parts of India, who leave their homelands and place their family relations at stake, this play would appear as a personal text of tribulations and trials they and their family members face every day, and speak to them in a language of emotions that is not dependent on translations.

References:

Ramanujan, A.K. Speaking of Siva. London: Penguin Books, 1973.

Yadav, Virendra Narayan (Ed.). Bhikari Thakur Rachnavali. Patna: Bihar-Rashtrabhasha-Parishad, 2005.

http://insightjnu.blogspot.com/2005/09/voices-bhikari-thakur-Shakespeare-of-20.html visited on 10 September 2010.

This article was originally posted on MuseIndia.com. Reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Namrata Chaturvedi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.