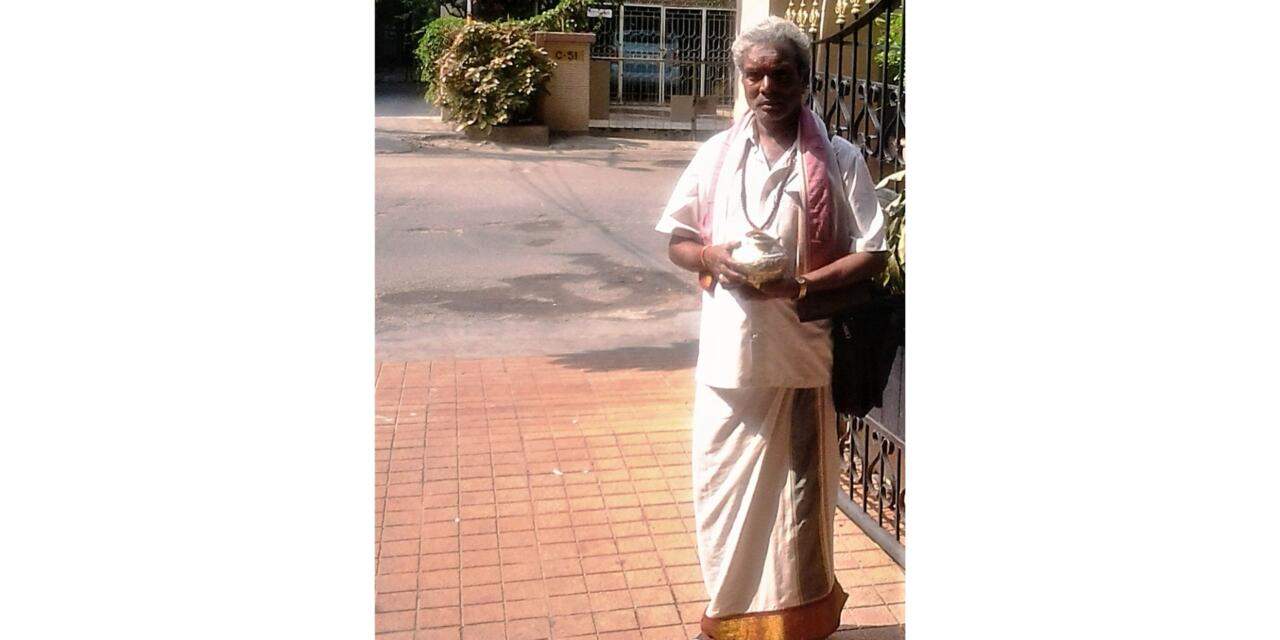

Attired in a crisp white dhoti with a red zari border, bleached white shirt and angavastram, one could mistake Krishna, a “Haridasu,” for a wandering pilgrim. He ambles along the silent city streets of Hyderabad, filling them with music that does not belong to this age. His voice carries the imprint of the past, of medieval balladeers that moved away from temples to recreate sonic sacred geographies as they meandered, incorporating local sights into free-flowing lyrical verses. Presently, his song entertains a now-invisible, anonymous public, residing in vertical buildings.

He is approximately 73 years old and originally hails from Mylapuram, Mehboobnagar District, but presently resides in the Shamshabad area of Hyderabad, Telangana. He identifies as being from the “Budiga Jangam” community, recognized by the Backward Classes Commission[1] as those “whose traditional occupation is begging.” The Budiga Jangams belong to the Scheduled Castes, a term officially designated by the Constitution of India to refer to those disadvantaged communities who have faced historical oppression, deprivation, exclusion and ostracization on account of their low social position in the existing caste, social and religious hierarchies in India. The traditional occupations of this community including hunting, seasonal agricultural labour, and garland making among others are decidedly under threat due to the combined effects of modernization, neo-liberal policies and globalization. It is believed that the term Budiga/Beda Jangam is used because they play certain traditional instruments such as sankham (conch-shell), nandiganta (cone and bell), tambura (stringed instrument) and baka which are musical instruments used for performing jangam kathalu (jangam stories).

It is unusual that Krishna refers to himself as a Haridasu, because Haridasus[2] are generally considered storytellers of “Harikathas”, a composite narrative form of the late 19th-early 20th century including drama, literature, science, dance, philosophical texts, poetry, dialogue and music, who received the extensive patronage of the Brahmin intellectual elite. The form provided the means to narrate stories and hagiographic myths of saints and provided multiple references to ancient epics and legends extracted from cultural memories of local regions. The social reformers and revivalists sought to build a cohesive Sanskritised[3] cultural identity to reflect the aspirations of the modern nation, free from the colonial yoke and shaped in the socio-political image of the upper castes. This enabled them to perform in “sabhas” (spaces as well as organizations involved in the promotion of fine arts) and other cultural venues meant for the elite. In the early part of the 20th century, Bhagavata Mela Natakams (dance dramas following Sanskritic and textual conventions with music, speech, dance and gestures) as well as “kathakalaksepams” were performed in the sabhas in Madras meant for religio-cultural education, apart from entertaining the audience and creating rasanubhava (experience of rasa or affect).[4] These were mainly performed by Brahmin troupes, trained in what is now understood as the Carnatic singing tradition.[5]

Standardization refers to the structuring and reorganizing of certain forms of singing, dancing and performing as “classical,” which included the elevation of certain compositions and composers over others in order to align with nationalistic sentiments and caste-based associations, pivotal to the nation-building exercise. The key paradox in this formulation was the simultaneous prohibition and reconstruction of elements within the very same art forms. The padam (the musical composition that accompanied dance recitals) as an art form was considered lower than the “kritis” and “kirttanais” (compositions written by renowned saint-performers during the Bhakti movement in praise of God) later performed by early 20th century upper caste musicians who developed the kutcheri (concert) format for the patrons or rasikas. Sanskritization denoted the linking of contemporary art and performance forms to what was perceived to belong to the ancient/medieval pasts and rooted in the presumed static and linear flow from the Golden (Sanskrit) Age. Its aim was to create the promise of unbroken performance traditions continuing from the past that sought to gain legitimacy from historical, written Sanskrit texts and their varied codifications.[6]

Krishna, however, performs verses as songs, but does not narrate episodes from the well-known epic tales. His performance is perhaps limited by practicality; the lack of multiple instruments and ensemble members could suggest that he cannot perform Harikathas in their entirety, even though the Haridasu is otherwise a sole exponent of the form.

Yet another member of the Budiga Jangam caste, Lakshmi, in a parallel conversation, scorned the usage of the term “Haridasu” to refer to Krishna and his fellow performers as in her opinion, they are mere “tandanana” (cymbal) performers. Without detracting from Krishna’s extensive learning, this may signify an aspiration for the Budiga Jangalu to be considered worthy of state recognition. Adopting the title of “Haridasu” could enable Budiga Jangalu to access institutional culture, since they have, over the previous centuries, remained at the periphery of cultural patronage. Conversely, it is possible that these performance traditions were subjected to co-option by the cultural and intellectual caste elite over the preceding centuries which repositioned communities of performers in a manner detrimental to their earlier status. Classicization involved the forging of purified “classical” traditions from the existing forms to serve the new nation as cultural propaganda. The nationalist movement’s re-ordering of cultural identity reflected a serious engagement with the notion of “purity” which sanitized many vernacular art and performance traditions of “sensuous”, “grotesque” or “lowly” elements and remained a tenuous space of contestation and eventual homogenization.[7] The concept of tradition juxtaposed with innovation and modernity in South Indian music and dance was the result of continuous negotiations between diverse class, caste, gender and religious assertions with differing power and authority.

The terms on which his profession is defined do no justice to the intensive training that Krishna attained through a lifetime of performing. As a child growing up in a Jangam household, each member of the family was taught “padyaalu” (verses) from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas and Itihasas (epics, local folk ballads, and histories).

For those who assume that “raga” (melodic forms) is only the preserve of classical music and its proponents, this is a reminder of the range of cultural interactions that took place between various art forms and practicing communities before the processes of standardization, classicization and Sanskritization regulated the cultural terrains of dance, drama and music and created false codifications of “high” and “low” forms during the early 20th century. The co-option of the sadir (courtesan dance) tradition by the Brahmin intellectuals around the turn of the 19th century demonstrates the reconfiguration of the practice into an “acceptable” art form as part of public sphere engagement.[8] This was done mainly for the puritanical middle class sabha audience, recently schooled in the “Classical Indian tradition”.

The connection between caste and musical traditions has a long history in the wider region of “South India”. T. K. V. Subramanian writes in his book Music as History in Tamil Nadu that the figure of the shaman musician (panan/panar), in the early part of the first millennium was as vital to the daily activities of the community as these artists’ societal positions were peripheral. The musician prepared battalions for war, communicated important public messages, mediated between lovers as well helped regulate everyday emotional interactions which Subramanian equates to the ‘sacrificial’ task of keeping chaos in order. However, they were seen as marginal figures, not belonging to the powerful social classes. With land granted to the Brahmans in the early medieval period due to their socio-religious position amidst burgeoning temple construction and agricultural development, artistic and performance activity came under the supervision of these communities and itinerant performers of yore fell into disfavour.

In continuation to describing skills received in a Jangam household, Krishna nostalgically describes his family’s contribution to the tolubommalatalu (shadow puppet plays) tradition, performed as one of the primary sources of entertainment in villages across Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Their performative functions also extended to the melukolpu (the singing of the first song of the day to wake up the deity). The family constituted a large group of thirty people or more, playing instruments such as tabla, harmonium and cymbals among other ritualistic accoutrements. This was a group fashioned in the manner of a “melam”: an ensemble with different people trained in different aspects of the performance. His mother introduced him to roles of female impersonation and he played characters such as Satyabhama, Rukmini and Jambavati with relative ease. “I had short hair and a reed-like voice then, didn’t I?” he quips, good-naturedly.

It was considered commonplace for performers from certain communities to travel to bigger cities, visiting houses to sing, playing musical instruments with human or animal accompaniments, in keeping with the extant performance traditions of agrarian communities in Andhra Pradesh/ Telangana. Krishna is one among many itinerant performers whose sole source of livelihood is imperiled due to existing employment and economic conditions. With the onset of neoliberal policies and an economy tipped to foreign capital, lower caste performers and cultural producers are increasingly subjected to socio-cultural and economic erasure. In light of their professions pitted against modern urban architextures, their testimonies and cultural performances speak the language of defiance and reclamation.

In response to the distress faced by crippled village economies, his family moved to the city to earn a better living. Many of his relatives built small houses in the outskirts of Hyderabad, Telangana in order to band together to support each other. Krishna travelled to work every Sunday and has since sung with the All India Radio, on the Vivid Bharati channel and has performed in Ravindra Bharati, one of the few large art and culture auditorium complexes in Hyderabad. He mentions with undisguised longing that he has never appeared on television.

He claims that his training enables him to condense 18 parvas of the Mahabharata into one “shloka” (verse composed in a specific meter), and six “khandas” (chapters) of the Ramayana into one “padyam” (verse). To many, this may sound like an ungrounded claim. However, he asserts that this device is essential to maintain an audience’s flagging enthusiasm for long performances due to dwindling attention spans.

The younger generations have learnt a portion of his large gift but have no interest in continuing this living performance tradition. Family meetings are generally woeful affairs where the future of the art is discussed by the elders but finds no takers. His four daughters are not invested in learning and reciting verses. He admits that the strains of music and drama that saturated his childhood home ensured that the learning process was osmotic, organic and unconsciously derived. He imbibed more than he could actively comprehend considering that active tutorship in music and performance was not the norm in his community. The present generations’ cultural education is severely hampered due to the diffuse migratory patterns of the performing family members who have relocated to different parts of the country.

Despite this, these performance practices have managed to remain in the hands of the Jangam community, who identify themselves with the new state of Telangana, but their art form is not considered among the class of performances belonging to the High traditions of performance. They are among many Scheduled Castes communities that seek redress from the state government for their chronic neglect and poverty. Krishna speaks of politicians from his home district who promised him a house, ration card and Aadhaar card (biometric identity card). He has never received any of these benefits. The Budiga Jangam community are mainly landless and presently work in a wide variety of sectors, including casual labor, agriculture, manufacturing, service, goods processing, domestic labour, mat-weaving, and livestock among many others.

The present Telangana government is invested in formulating a cultural identity that suits the demands and aspirations of the region. This includes focusing on festivals, performances, art and culture linked to the life, labour and cultural identities of its people, which best communicate the ideals on which the new state was created. Krishna hopes that his community, mostly concentrated in Telangana, will receive the state patronage and attention they deserve.

Curious to witness the result of this condensed wisdom, I ask Krishna to recite a couple of phrases from his vast repertoire. His voice cracks from the strain of singing to vacant balconies and he mentions that it is in need of an operation. He can barely manage to croak a few words of a song. So, we confine ourselves to the hues and tones of his recital. Krishna ends wistfully, “The Haridasu is always alone; he needs no accompaniments.”

Padyam:

Jagati payi maanava ee janmambu dorakadu

Dorikina purushuduku putrutaradu

Putrudu puttina paridhi manchidiraadu

Vachchina bhaagyambu vochchutaradu

bhagyashaali putra *word missing* (most probably koodika, according to the structure) chaikoodadu

koodina vitarana kalagutaradu

vitarana kaligina vela shantamaradu

shantam dorikina satyam aradu

satyamu dorikina harinama smarana haddu

Translation

Many of the padyas that he sings perhaps belong to the oral traditions of his own community. They seem to share many ideas in common with other knowledge traditions that circulate in different spaces. This poem uses the muktapada grastam as alankaram (embellishment) i.e. beginning the ensuing line with a concept introduced in the former and extending the range and scope of meaning. Telugu allows for displacement of words, as its grammatical structure does not follow the English mode of Subject-Verb- Object agreement. Therefore, even though there is continuity, a certain disorderliness in word pattern (familiar to Telugu poetry enthusiasts) may be visible.

O mortal, to be born as a human being on earth, is rare

To exist and further bear a child is rare,

For the child to understand its purpose and the span of its existence,

Is rarer still

The fortune that blesses the brave is fickle

The fortunate should not fear its leaving; for, when one has amassed fortune,

Being generous is rare

If, you were generous, could you be assured of peace?

Even if peace were possible, finding Truth is rare

When having found Truth, the path to his Name is the only goal.

Padyam

Anni daanamula kanna adhika daanam eedi?

Talli tandrulu kanna daivam edi?

Satyasheelam kanna jagatitapam edi?

Santosham kanna swargam edi?

Dayakanna mikilli dharmam edi?

Rrunam kanna eruguko sukham edi?

Sujana sampatti kanna chooda laabham edi?

Dharani apakeerthi kanna maranam edi?

Krodham kanna chaturam edi?

Anganaamani kanna raminche mani edi?

Rama!

This is a prime example in the poetry of the region that provides hidden reasoning in the question-answer format. This addresses Rama in the voice of the bhakta (“devotee”) while seeking knowledge. This also allows for wordplay, irony and recourse to common-sense “folk” wisdom that the communities explore in their performances. (Special thanks to Ms. Kanda Bhaskaram and Lt. Mrs. Sarada Manthena for their help with Telugu poetics and translation)

Translation

Of all forms of wealth, which is the highest?

(in the manner of singing, danam may also be “giving”/ being charitable i.e. of all the acts of giving, which is the most hallowed?)

Is there a greater God than one’s parents?

Can there be a higher austerity than truth and force of character?

Is there a heaven more desirable than a state of happiness?

Leaving aside compassion, is there a higher duty?

Know this: where is the happiness in seeking loans and favours?

Is there greater wealth than the possession of good qualities?

Isn’t Death preferred over harm to reputation?

Is there any cleverness in a show of rage?

Who is more worthy of respect above an exceptional woman?

Rama!

[1] Report of the Backward Classes Commission, 1970

[2] Rajagopal, V. “Traditional Intellectuals and Colonial Modernity: Life and Worldview of an Intellectual from the Telugu Region.” Social Scientist 44, no. 11/12 (2016): 77–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24890261.

[3] Srinivas, M.N. 1956. “Sanskritization and Westernization.” Far Eastern Quarterly 14 (4). (August)

[4] This performance involved elements of drama, humour, satire among others requiring diverse histrionic talents amounting to versatility on the part of the Harikatha exponent in addition to an intimate knowledge of bhakti lore and a large repertoire of devotional songs of diverse types.

[5] Amanda J. Weidman, Singing the Classical, Voicing the Modern: The Postcolonial Politics of Music in South India

[6] Matthew Harp Allen. “Standardize, Classicize, and Nationalize: The Scientific Work of the Music Academy of Madras, 1930–52.” Performing pasts: reinventing the arts in modern South India (2008): 90-129.

[7] This could also have been a response in keeping with the prevalent norms of colonial Victorian morality which classed Indian art and cultural production as “monstrous”, among other descriptions. See Partha Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters- A History of European Reactions to Indian Art, Clarendon Press, 1977.

[8] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230321809_2

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aprameya Manthena.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.