More than ten years after Words without Borders presented its first issue of theater in translation, we’re back at it again. Much in the world has changed in the intervening decade, and in our current issue, we present five works of microtheater, a genre over a century in the making that has taken on new urgency at a moment of global economic and political upheaval.

Though recent events have made this issue ever more timely, the original idea to publish a second theater issue arose in 2015 when, invited to participate in the Center for the Humanities’ Translation Mellon Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research at the Graduate Center, CUNY, I found myself in the midst of a discussion with various participants about theater in translation. As the conversation became more and more animated, our discussion quickly led to the next logical question: why not publish a theater issue of WWB and work together to stage the works published in the magazine?

My colleagues and I began to discuss the possibilities in earnest. Yes, we all agreed the issue was a good idea, but could we make the issue more meaningful, more immediate? As luck would have it, WWB board chair Samantha Schnee had met Sarah Maitland of Goldsmiths, University of London, just weeks before. After a couple of initial conversations, Sarah suggested we consider an issue of microtheater: though its origins (as she explains in her introduction to our issue) stretch back over a century, it’s a form that has gained steam once more in light of the global financial crisis that began in 2008. The form was exciting and often topical. We were off to the races. At the time, I’m not sure any of us imagined 2016 would be such a politically tumultuous year on a global scale—impeachments, Brexit, Trump—but quite without our planning it, both the genre of microtheater and the themes to be found in our issue took on unexpected urgency.

Microtheater, as Sarah remarks in her introduction to our issue, is notable for its “capacity for instruction, for renovation and contemporaneity,” and its “immediacy of response to some of the most urgent questions of our time.” It should come as no surprise, then, that the five works we selected for our issue, from five different countries, capture the anxiety and uncertainty that define the zeitgeist.

José Ignacio Valenzuela’s Number Six and Roberto Athayde’s Visitors from on High, A Tragicomedy in Science Fiction transport us beyond our quotidian mundanity at the same time they examine the worries inherent to it. In Valenzuela’s Number Six, a distrustful woman debates whether she ought to allow a stranger whose car has broken down in the midst of a thunderstorm into her home. Athayde, meanwhile, presents us with outer space so that we might reflect on terrestrial concerns around man’s place in the world and in the universe at large.

In No Direction, Spanish playwrights Miguel Alcantud and Santiago Molero present us with a nameless man who appears to be kept in captivity by a woman, Ana, who insists he cannot be let out. In the cyclical conversation between the two, which almost resembles a call-and-response but serves to disorient rather than reinforce commonality, the man’s inability to fully comprehend his situation is mirrored in the audience’s similar struggle to make sense of a situation bereft of the typical structural markers of conventional narrative.

If Andrei Platonov’s Grandmother’s Little Hut and Jerzy Lutowski’s Love Thy Savior, Part Three adhere to more conventional narrative structure, their power lies in their use of historical precedent to comment on contemporary societal questions. In Platonov’s unfinished play from 1938, two young orphans seek out their promised land in the form of a hut where the grandmother of one lives. Lutowski, meanwhile, takes us to Inquisition-era Spain, where intolerance demands a bold choice of a young Jewish woman with little prospect of escaping the harrowing implications implicit in all of the options before her.

While the micro-plays we’ve published make their own statements and take their own stands, we also sought to further a cause that’s long been dear to us: championing the work of the “shadow heroes of literature,” as Paul Auster has appreciatively described translators. Because the world of theater translation was, in large part, mysterious to us, the magazine decided to publish two essays by working theater translators Paul Russell Garrett and William Gregory to shed light on the challenges particular to this very specialized form of literary translation. Their essays provide fascinating looks not simply into the work of the theater translator, but also into the dynamics of modern theater companies staging international works.

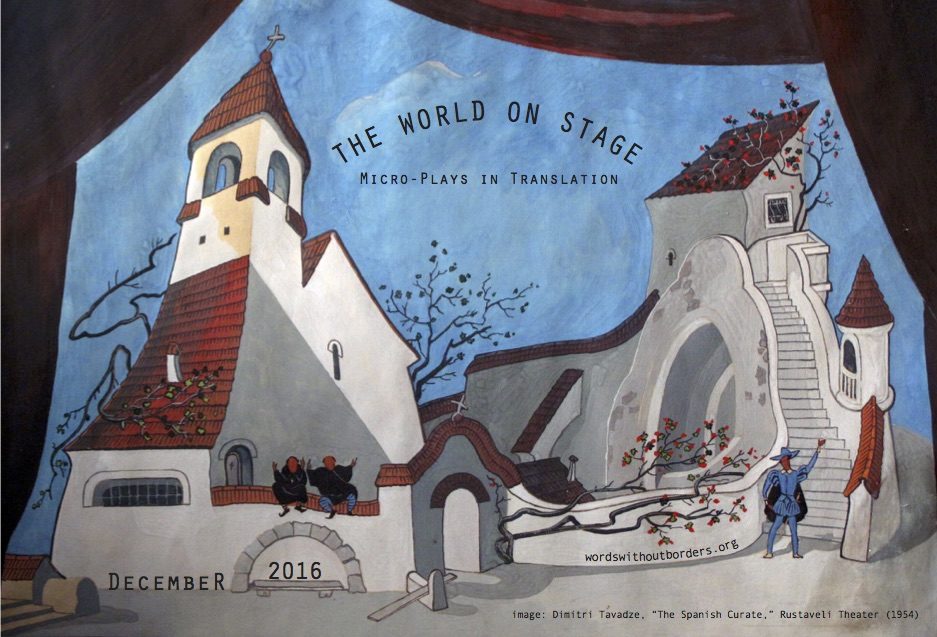

We had a chance to experience these dynamics firsthand as we endeavored to stage a reading of three pieces from the issue in New York together with our Sarah and our CUNY collaborators Debra Caplan and Cheryl Smith. On December 13, in collaboration with the Center for the Humanities’ Translation Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research at the Graduate Center, CUNY, Words Without Borders will present “The World on Stage: Readings from Micro-Plays in Translation” at the Martin E. Segal Theatre, hosted by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh. More information can be found here.

In these uncertain times, the works in WWB’s December issue remind us that we are hardly the first people to struggle against malicious intolerance used for political gain. Yet they also strike a hopeful note, reassuring us that artists have not abandoned their historical role in revealing the error of our ways and recognizing the value in our difference.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eric M. B. Becker.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.