Seuls

Written, Directed, and Performed by Wajdi Mouawad

The Wilma Theater, Philadelphia Nov. 29-Dec 11, 2016

Lebanese-Canadian theater artist Wajdi Mouawad frames Seuls, his one-man show about the shoals of cultural assimilation, within the protracted adolescence that is graduate school. Harwan, his depressed and isolated protagonist, is thirty-five, devoid of nourishing personal relationships, and fifteen hundred pages into a doctoral dissertation on the concept of the “sociology of the imaginary” in the solo performances of his idol and fellow Québécois, the acclaimed theater director Robert Lepage.

We meet Harwan wearing nothing but his underwear and eyeglasses. He enters without fanfare as audience members are still jabbering and sheepishly delivers a preamble to what might be an insufficiently prepared oral defense. He is interested, he announces, in eminently worthwhile if potentially insoluble questions regarding “our ability to live together and put up with our differences,” but admits that he has not to date managed to arrive at any any answers. The narrative of his dissertation, like that of his life, lacks a satisfying conclusion.

Borrowing liberally from the facts of his own biography, Mouawad creates an internally riven protagonist whose family fled civil war in their native Lebanon when he was a young child, and who now finds himself feeling nostalgic not so much for a homeland as for a fantasy of the more fulfilled version of himself he might have become had he not been forced to emigrate. Harwan recalls passing his days in Lebanon counting the stars in the night sky and painting, projects he gave up long ago in favor of the pursuit of tenure, a goal that seems less and less desirable the closer he comes to achieving it. The carceral ambiance of his apartment is enhanced by the fact that his temperamental old rotary telephone has a mind of its own; Harwan is perpetually dialing out, missing calls and much-needed connections with emissaries from the outside world. “Seuls” can be translated as “the alone ones,” “the lonely ones,” “the singles,” (or bachelors), “the only ones.” And Harwan is all of these.

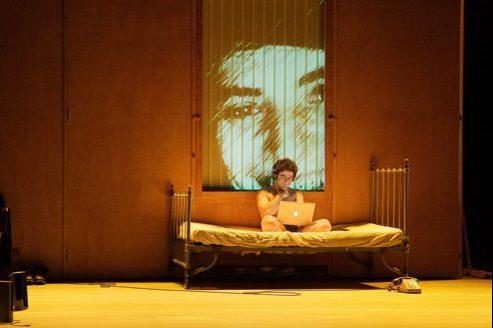

Seuls, Written, Directed, and Performed by Wajdi Mouawad. The Wilma Theater, Philadelphia. Photo credit Thibaut Baron

One of the inbound voices that periodically pierces our protagonist’s solitude is that of Professor Rusenski, who calls early in the play with some bad news, the stuff of every Ph.D. candidate’s nightmares: Harwan’s dissertation advisor has died unexpectedly, which means that in order to receive his degree he will have to complete his research many months ahead of schedule.

A key component of this research is a long-anticipated face-to-face interview with the man himself, Robert Lepage. Professor Rusenski suggests that Harwan simply asks to move the meeting up, an audacious request that, Harwan insists, would be “like asking to meet with the Pope tomorrow.” But request it he does, even though it means traveling to Saint Petersburg shortly after his father has had a stroke and fallen into a coma. Before leaving town, Harwan stops by the hospital for a wrenching one-way bedside chat. According to a nurse, Harwan can help his father by speaking to him in his mother-tongue, Arabic, a language that hasn’t come easily to him in many years. This basic, frustrating barrier between them turns out to be the tip of an iceberg, prompting a twenty-minute monologue that is more despairing soliloquy than earnest attempt to connect with a man who, to hear Harwan tell it, has never respected him. More importantly, Harwan resents his father for depriving him of the life he might have led in the Middle East. With his life grinding inexorably closer to abject misery and failure and thoughts of suicide crowding in, Harwan can’t help but fetishize the road(s) not taken. As in Mouawad’s modern tragedy Scorched, which played at the Wilma in 2009, the past overwhelms, foreclosing the possibilities of the future.

If being an immigrant is something like being an “eternal student,” Harwan’s comprehensive examination on disorientation comes when he gets to Saint Petersburg. Lepage has departed unexpectedly for San Francisco, so the trip has been a waste of time. Then, when he opens up his suitcase and finds not his own personal effects but a stock of art supplies, all the rules of the play change—Harwan begins to paint, and as he covers more of both himself and the startlingly expandable set, the experience starts to feel more hallucinatory than real. Surrounded by violent, vivid, full-body footprints of himself that recall Yves Klein’s anthropometry paintings, Harwan hears voices explaining that there has been an accident, that he is the one lying unconscious in a hospital bed, not his father, and we in the audience are abruptly forced to reassess nearly everything that has come before. Just as his last ties to reality appear to be stretched to the point of snapping, Harwan hears another voice, that of Professor Rusenski, apparently the most devoted dissertation advisor the world has ever known. In combing through the scribbled notes Harwan left behind before falling into a coma, Rusenski came upon Harwan’s long-coveted conclusion. In Lepage’s solo performances, as in life, limitations and possibilities are not, Harwan has finally grasped, opposed to one another. The limit is the portal, a beginning.

Peter Brook wrote, “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across and empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.” Though Mouawad’s solo swells considerably beyond such austerity, his subject is still a man traversing an empty space, its contours initially as confoundingly indistinct as his own. In recent years, Lepage has become the object of considerable scorn for costly, maximalist theatrical endeavors such as his 2013 Ring cycle at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, which starred a ninety-thousand pound, glitch-prone automated set, unaffectionately nicknamed “the machine.” Despite their own susceptibilities to the seductions of excess, Mouawad and Harwan are stunning as minimalists. Mouawad is interested in the pith, not the rind. And in turning to making art rather than simply studying it, Harwan is at last able to take control of the way he moves through both his outer and inner worlds, to embrace limits, and to be free.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.