Author: Rathsaran Sireekan

Contemporary art’s desire to be “contemporary”, for many practitioners, interestingly comes with the impulse, or some may say necessity, to bring back the past to the “now.” Major trends in contemporary dance, Yvonne Hardt observed, have seen not only reconstruction of or reference to historical dance pieces, but also the conversion of the stage into a site for archiving dance performatively. But the nexus between the new and the old in performing arts is rarely considered in the context of globalization and postcolonial debates. This text wants to be part of a growing body of work aiming to fill this gap.

The colonial or semi-colonial [1] process of modernization, indeed, often results in local cultural traditions and art forms being annihilated or repressed and reduced to something “exotic.” It is a process that puts Western Weltanschauung at the center of the aesthetic universe. In this line of thinking, decolonization should mean a revival of the obliterated or those displaced as the “other” by the colonial or semi-colonial process of “othering.”

But this revival usually taken to be synonymous with the decolonization of contemporary performing arts is not always a straightforward process. First of all, in order for a tradition to make a comeback, it will have to pass the test and qualify the category of the “contemporary.” As Frederik Le Roy aptly suggests, the “contemporary” is more than a simple descriptive category of something produced contemporaneously or at the current moment, but “a performative category that rehearses ‘prior delimitations’” (Butler 11) about legitimate and illegitimate artistic practices. The contemporary regulates the field.” [2] For practitioners in the globalized art world, being deemed “contemporary” is a pre-requisite of their practices’ ability and opportunity to orbit various international performing arts festival circuits across the globe. But one may ask what is the “contemporary”? [3]

Secondly, the relationship between decolonization and the revival of a local tradition is a complicated one. This is because the process of decolonization itself pivots on a set of Enlightenment values—of reason, science, skepticism, individualism, humanism and egalitarianism—while local traditions are, more often than not, heavily enmeshed in non-democratic ideologies which were to be repressed or eradicated, ceremoniously or structurally, by the colonial or semi-colonial process of modernization.

Furthermore, both the colonial or semi-colonial processes of modernization and decolonization projects are similarly informed by Enlightenment thought. This fact makes it not so easy to discern if an attempt to innovate by bringing local traditions back to the contemporary performing space reinstates colonial processes of modernization, or rather departs from it.

The practice of Thai contemporary performing artist Pichet Klunchun, who is no stranger to Belgian podium art spaces and festivals, allows for a nuanced discussion of the intriguing entanglements of decolonization and the revival of tradition in the contemporary context. As his practice travels to different festivals across the world, a glimpse at how the artist finds the language of the “contemporary” in his renewal of khon —a centuries-old Thai classical art of masked dance, impacted by the semi-colonial process of modernization in Siam/Thailand—will perhaps give us a sense of what the “contemporary” in the global context of performing arts is and if that can be qualified as a move towards decolonization.

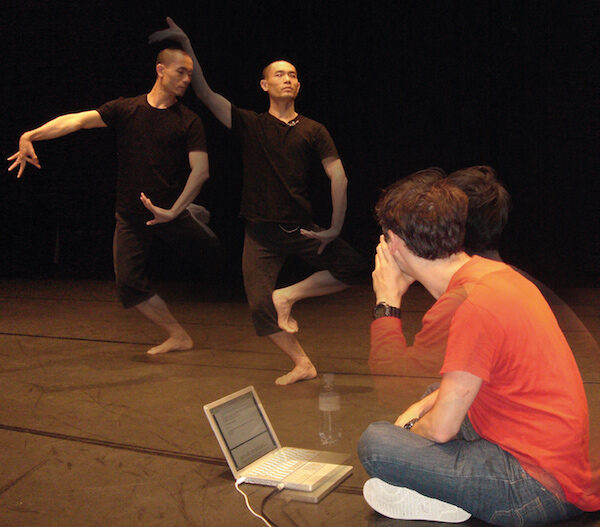

Belgium itself has welcomed Klunchun on several occasions, including his internationally acclaimed collaboration with Jérôme Bel Made in Thailand at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts (KFDA) in 2005. It was Frie Leysen, the founder and then-director of the KFDA who spotted this intercultural collaboration (which had premiered earlier in Bangkok) and invited them. The KFDA immediately invited Klunchun back in 2006 where he performed I am a Demon. His collaboration with Bel was then reproduced at the Kaai Theatre in 2011 with a different title: Pichet Klunchun and Myself. At the first edition of the ASEM Cultural Festival at Bozar in 2018, Klunchun brought back I am a Demon to the Belgian and international public. And this year in May, he will collaborate, yet again at the Kaai Theatre, with Taiwanese artist Chen Wu-Kang on a show called Behalf.

The epic and power

Asked during one of the interviews I had with him what his practice is in a nutshell, Klunchun answered: “My practice is about posing questions.” In the habit of shaking up the status quo, his works have demonstrated a clear trajectory of critical thinking of Thai culture, Thai dance, with the body and the techniques that come with it, with my career as an artist and with ‘me’ at different stages of life.”

From the narrative he provided, this critical thinking came with his first encounter with the West and its modern and contemporary dance. Particularly when he received funding from the Asian Cultural Council, an American non-profit, in 2001 to travel to the US and participate in a cultural exchange program in New York and at UCLA and Duke University. It was also the first time for him to meet and work with “real” dancers. (“Real” in the sense that they can make a living out of their dancing career, especially when there are infrastructures, either social or institutional, which support not only their livelihood but also their identity and legitimacy as dancers.) This intercultural encounter where differences give way to self-reflection “Western dance is informed by logic whereas Thai dance is fueled by faith and beliefs.” Such a realization pushed him to question what in Thai dance is beliefs and what in it is techniques. This critical thinking of Thai classical dance inspired him to create I am a Demon (2004-5) — his first solo show that has led some people to think that he has the intent of destroying the traditional art of khon.

As with his other pieces that were to follow until 2013 [4], I am a Demon presents a highly technical body of a well-trained khon dancer. But instead of being clad in the usual glittering and passionate-colored elaborate khon attire topped with either a headpiece, Klunchun only wears a body-conscious top and loose training pants—both of which are to be stripped off as the show moves on, leaving him to perform this sacred art almost naked: just his bare body and the underpants. This is unprecedented for an art form so closely attached to the royal court culture. For fans of contemporary performing arts, the choice for much simpler and more comfortable clothes can only be a common sense. But bringing back a faith-bound art—inseparably entangled with the centuries-old royal court culture of the absolute-monarchy of Siam, now Thailand—to the contemporary stage nearly naked means more than an act of anti-anachronism.

Speaking at the Aksra Theatre in Bangkok in 2015, Klunchun explained to the Thai public why he does away with the khon attire:

“We [Thai dancers] believe that Thai performing arts originate from Nataraja or Nagaraja (king of the nagas), the Lord of Dance, a devotee to the Hindu god Shiva. Then, it was passed on to Bharata Muni before being passed down to the mortal world. We also believe that practitioners of Thai performing arts are protected by these great masters who serve as guardians. Therefore, performing artists are special persons and this is a sacred art. Believing that we are special, we are very concerned with anyone tampering with our head. You can’t put your shoes on your head because you’d say it’s improper. But who says it’s improper. [Placing a shoe he requested an audience member to throw onto the stage on his head] It’s culture. The danger of “culture” is when “culture” means judging things without reasons. [Pointing to the walls of the Aksra Theatre covered with seas of friezes of elaborately clad absaras (female angels), he announced:] These things on the walls here are considered “culture”. We don’t count it as “Thai dance” because they are adorned with clothes and headgear [which themselves are the embodiment of a specific set of beliefs.]…Therefore, let’s strip away the clothes so that there is only the bare body. Without clothes, what remains is human. There are no longer devas (“angels” in Hindu). What is hidden in the movements of our national art? What do these curves mean? What were the choreographers thinking? [A series of drawings of abstracted representation of the body doing Thai dance then was projected onto the screen.] All that is left in the end are lines. Take away the bark, and there remains the heartwood.”

Focusing on the human body, the artist, by stripping away the usual khon gear, wields the power of reason and extracts beliefs out of the art of khon—a tradition of dance that is solely dedicated to the performance of Ramakien—the Thai appropriation of the Indian Ramayana. “Rama”— the reincarnation of god Vishnu and the protagonist of the epic whose narrative has buttressed power structures and relations in the Siam/Thai culture and society for centuries—is the source where the artist’s country’s current dynasty draws the names of its monarchs from.

But instead of perpetuating the inseparability between the art of khon and the beliefs embedded in the epic Ramakien, Klunchun in I am a Demon, first, shifts the focus onto the body of an individual dancer. Second, the artist deconstructs the coherence of the spectacle on stage into different strands of narrative pertaining to how the performing body the audience is witnessing became a khon dancer in the first place. These “innovations” represent, at once, a humanistic turn, an even more democratic interpretation of the khon art form [5] and a critique of modernity that comes with such humanistic/democratic take on the traditional art form. The show starts with the artist drawing attention to his body by stretching and straightening it up as if to prepare it for a performance. He then seizes the fat flap at each side of his waist as if trying to get rid of them or put them in order—a way to acknowledge that this imperfection makes the current body on stage a human body as opposed to those of the godly reincarnations in the Ramakien.

But the show takes yet another surprising turn, when the stage, instead of witnessing a full-length technical demonstration of the heavily trained khon body, is filled with the voice of the artist’s teacher being interviewed about why he gave the role of the “demon” (yak)—and not the different reincarnations of the gods (phra) or the monkeys (ling)—to Klunchun. A Thai woman’s voice translates what Pichet’s teacher has said into English: “he has the right body for the yak which suits his characteristics. His body wouldn’t allow him to make a good phra or ling.” Then a Singaporean male voice interviewing the artist’s teacher emerges, followed by a Western male voice doing the same. These are then translated into English by the same Thai woman. After that, Klunchun starts striking some khon postures along with his teacher’s instructions, unpacking the ontological coherence of the spectacle of the dance itself as a given. Then, the picture of him and his teacher fills the backdrop of the stage. The show ends with the Singaporean male voice asking if it’s true that he has transformed the traditional beauty into something a contemporary audience can appreciate. His reply in the recording is that he is not into the conservatism whose followers think whatever outside the prototype of the traditional masterplans is wrong and is not art. Instead, it is a “concept” that leads him to develop a piece of work. “If I know what that is, I will work towards it. I don’t just repeat what has been done before time after time.

It is obvious from the above that in order to bring khon as an art form back to the present, the contemporary—be it Thai contemporary or international contemporary at large, which will have to be further discussed—Klunchun “modernizes” khon with the penetrating power of reason, the key product of Western Enlightenment. Other aspects of modernization in the piece include the quintessentially modernist technique of abstraction—when he reduces everything in khon postures to mere lines—and modernist thinking in his definition of “art” as the ability to innovate, to “make it new”—as opposed to the Eastern understanding of “artistry” as the ability to emulate as closely as possible what the masters have achieved. And especially when his notion of innovation is intertwined with the modernist legacy of conceptualism in art. Along with the shift from rituals and beliefs, informed by deism and feudalism, to a more humanistic and democratic interpretation of the body of khon dancers, these are all clear markers of Westernization/modernization. But do they automatically subsume Klunchun’s practice under the same semi-colonial process of modernization which Siam during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries underwent? If that is the case, should his practice automatically be considered re-affirmative of the supremacy of Eurocentrism and thus rendering the non-West to always be the belated followers in this unidirectional and progressive linearity of time. And if it is really belated, how do we explain the fact that Klunchun has continuously been enthusiastically welcomed by curators of numerous international performing art festivals across the world? What does this have to say about the “contemporary” especially in relation to Western modernity in the context of globalization and postcolonial debates? The fact that modernization characterizes the “contemporary” in Klunchun’s practice makes it difficult for some people to wholeheartedly claim that his art represents a trajectory which seeks to decolonize. However, as pointed out in the beginning, since both modernization and decolonization similarly rely on Enlightenment thought, the question to ask is if a practice informed by Westernization/modernization can be considered to be decolonizing as well? Is modernization essentially an antithesis of decolonization?

Two speeds

When I asked the artist at the ASEM Cultural Festival (which is dedicated to linking Europe and Asia together) taking place at Bozar in 2018 why, out of numerous items in his repertoire, he specifically decided to bring this old piece, created more than a decade ago, to the Festival. He replied:

“I want to convey [to the European audience] that this traditional relationship between a teacher and his or her student which I had with my teacher is disappearing from Asian societies. I am talking about the way of teaching and learning dance that has more to do with passing down the spirituality that comes with practicing and nurturing the art than just learning the techniques, the choreographies to get the Fine Arts degree as young dance students these days do. When dance has entered the official educational system, it has pushed people and spirituality out of itself.”

Multi-faceted as any good piece of art is, although Klunchun’s I am a Demon is technically informed by Enlightenment thought and modernist artistic legacy, the piece’s key concept targets the impact of Westernization/modernization particularly on dance education in his home country and region.

For Klunchun it is fair to say that, in the context of Southeast Asia, the “contemporary” originates in the West and over time has spread to other regions including Southeast Asia. His is definitely a historicist understanding of the “contemporary,” of time as linear progress, but that, for him, does not seem to prevent his practice from traveling the world:

“I think it is inevitable to admit that we acquire contemporary art and culture from the West, but what I think makes curators of international festivals invite me to take part in their shows is probably the local specificity of the place I come from. I think they want to know what is the context of “contemporaneity” in Thai society and how it has evolved. Generally, I think that they are in search of new artforms which reflect locally-specific issues. So in terms of the creative process, we are not interested at all in what curators or festivals may want. We only work on the issue that we want to work on and speak about.”

Firmly placing his explanation of the “contemporary” in the historicist conceptualization of time as unidirectional and progressive linearity, Klunchun’s understanding of the contemporary unequivocally reveals an overlapping two-speed “contemporary.” He provided that “although critical thinking and institutional critique has been around for a while in the West, for Thai audience it is still electrifying and new for the audience at home.” (At the moment of the interviews and the writing of this article, Thailand is still an undemocratic country under a military government. This makes it not easy for the artist to do his critical thinking on stage in his own country, but he still feels he has the right to express his opinion.) And indeed, for some people, the dichotomy between the local and the global may sound like a new round of exoticization of what is displaced as the “other” by the colonial or semi-colonial process of othering. But as the artist pointed out, the fact that his works travel does not prevent them from directly engaging with the needs of people at home regardless of whether or not curators in the West would deem his practice or issues being tackled dated:

“In order for one’s practice to travel across the world, it is unavoidable to adopt the Western method. But instead of focusing on what the audience in the West would like to see, I apply the Western methods to think about issues at home—a kind of thinking that makes myself and my audience understand their culture and the power structures that operate within it better.”

Furthermore, for an artist who brings the centuries-old khon art form to the world, “contemporariness” does not lie in the practice’s style or technique. “A lot of contemporary works make use of classical ballet. In fact, ‘contemporariness,’ for me, can be embodied in any form, but the crux of the matter is the issue your practice is addressing and (re)presenting: that makes a work contemporary.”

In this particular empirical evidence based on Klunchun’s practice, it might be possible to ask back why the state of “belatedness”—the fact that it engages with Enlightenment worldviews originated from the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe—is approached with such skepticism in the critical discourse in the field of contemporary performing arts. To attempt to respond to the critique that “belatedness” prevents an artist’s practice “to expand their field of influence and recognition beyond regional borders,” [6] the trajectory of Klunchun’s practice beckons to us to ask why it is necessary to be “influential”. Who and what defines “influential”? Does this notion of “influence” in fact embody the expansionist ideology of (neo)colonialism in the contemporary? Can this critique of, and obsession with “belatedness” inflicted on such a non-Western practice as Klunchun’s be seen as another round not only of exoticization but, importantly, of deprivation of rights to democracy and human rights of the colonized denied by the colonialists during the nineteenth century and reclaimed during the second half of the twentieth century at the height of the wave of decolonization?

Pure culture?

It is undeniable that modernization/Westernization informs Klunchun’s practice. But, at a closer look, one cannot help but noting that I am a Demon, despite its fundamental reliance on Enlightenment values and modernist artistic legacies, deploys a technique that also makes it very “contemporary”. Hardt has observed that “…making the dance stage a site for archiving dance performatively ha[s] become major trends in contemporary dance.” Klunchun’s mobilization of dialogical “performance” between different voices in I am a Demon does just that, hence deserving a consideration of being “contemporary”. Klunchun’s method of archiving his own dance on stage puts an emphasis on the historicity and performativity of the practice being archived. It lays bare and heightens the constructedness [7] of khon as an art form and the coherence of the artist’s own subjectivity as a khon dancer.

Literally setting two dance traditions in conversation with each other, Pichet Klunchun and Myself, Hardt argues, makes transparent that Bel’s contemporary dance style is as culturally and ethnically marked as Klunchun’s Thai khon dance [8]. The intercultural piece shows that a conceptually driven choreographic endeavor like Bel’s demands as much explanation with regard to codes as does a culturally distant dance form like khon. The piece, in the tradition of Joann Kealiinohomoku, according to Hardt, exposes contemporary European dance as a particular form of “ethnic” dance—[9] a deconstructive trajectory which, in the tradition of Dipesh Chakrabarty, results in a provincialization of Europe.

Other choreographic works by Klunchun which seek to question the coherence, influence, and superiority of the West include Chui Chai (2010)—which explores, however without being judgmental as the culture for Klunchun is never pure, how the Thai society has been transformed by its appropriation of Western values. Another of such pieces is Tamkai or Hunting the Chicken (2013) which calls into question the notion of beauty in both Western and Thai dance aesthetics.

A glimpse at Klunchun’s works raises important questions about what kind of requirements a non-Western practice has to fulfill in order to be included in the boundary of the “contemporary.” In the particular case of this Thai artist whose works orbit the globe, bringing a traditional art form enmeshed in a feudalistic court culture to the “contemporary” means subjecting the performing body to go through a modernization/Westernization process. Yet, far from resting complacently with the coherence and indisputability of a subjectivity informed by European humanism, Klunchun shows an acute awareness of the constructedness of such a category. Through the act of archiving and dialogical interchange, he turns the “performance” on stage into “performativity”; the former presupposes a stable identity of the performer while the latter posits no coherent subject behind the “performance, reducing it into a mere series of recitations which brings about a temporary effect of an identity.

The paradox of the artist’s practice lies in the fact that as soon as he seems to confirm the legacy of European Enlightenment, he is also vigorously seeking to decenter the West, decolonizing its knowledge, taste, legitimacy and influence. Belgian fans who are looking forward to his new collaboration with Taiwanese artist Chen Wu-kang at the Kaai theatre this upcoming May are told to expect a series of improvisations which delegates the power of decision about what is happening on stage to the audience. This once again confirms the paradox in relation to the nexus between modernization and decolonization in his practice. In this new show, inasmuch as he will be mobilizing the democratic strategy of participation which can be traced back to the Enlightenment, he will also be decentering the Western Romantic/modernist notion of the “artist” as a genius who places himself/herself at the center of the creation and the creative process.

One could say that on one side of the coin, Klunchun seems to be an advocate of Jürgen Habermas who sees the “contemporary” as an unfinished project of modernity. Others looking at the other side of the same coin could say his practice resembles that of the postmodernists/poststructuralists like Foucault and Deleuze whose works seek to critique modernity. A consideration of Klunchun’s practice indeed reveals not only the uncanny proximity but coexistence between modernization/Westernization and decolonization—a dichotomy which itself rests on a historicist idea of time as a linear trajectory: that modernization took place first; then followed decolonization. Despite Klunchun’s own historicist understanding of the “contemporary”, the fact that the above analysis shows the coexistence between modernist and postmodernist traits as well as modernization and decolonization in his practice may impel us to rethink our understanding of the “contemporary”, especially in relation to non-Western practices, as a space and time where divergent temporalities and geopolitical realities coalesce. If this understanding of the “contemporary” holds true, perhaps the act of designating something “anachronistic” or “obsolete” may no longer be legitimate as it reinstates the imbalanced power relations which buttress and propagate Eurocentrism. In declaring a revival of a traditional art form “obsolete” while it, in fact, benefits people at home or/and people with comparable experience elsewhere in the world, one has to rethink for whom the “contemporary” is and who decides if something goes into obsolescence.

[1] As Thailand was never officially colonized. Jackson, Peter. (2004). The Performative State: Semi-coloniality and the Tyranny of Images in Modern Thailand. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 19(2), 219-253.

[2] Le Roy, Frederik. (2016). Contemporaneities. On the Entangled Now of Performance. Documenta, 2016(2), p. 17.

[3] Hardt, Yvonne. (2011). Staging the Ethnographic of Dance History: Contemporary Dance and Its Play with Tradition. Dance Research Journal, Summer 2011; 43, 1, p. 27-28.

[4] Black and White (2011) is the last work that deploys the dancing technique of khon whereas Tam Kai (2013) is the first work not to rely on the khon art form.

[5] According to Klunchun, khon began as a dance performed in religious rites and accompanied only by sacred songs without any narratives during the Ayutthaya period (1350-1767). Then in the early Rattanakosin era (1782-1851), the art form began to be performed with the narrative of Ramakien. In the reign of Rama VI or King Vajiravudh which lasted from 1910 to 1925, khon was dramatically Westernized and democratized: male and female characters of the Ramakien performing khon no longer had to wear masks, giving a greater visibility to each dancer’s individual face while the characters playing monkeys and demons remained masked as they were not humans. Sexual and gender distinction between male and female characters became more observed and pronounced. With more narrative songs composed for the performance, khon began to be performed in theatre instead of outdoors. (Siam had its first theatre in this reign.)

[6] Barba, Fabián. (2016). The Local Prejudice of Contemporary Dance. Documenta, 2016(2), p. 57.

[7] he emphasis on the constructedness of the art form, in turn, brings back Klunchun’s emphasis that ‘khon itself, like culture, is never pure as Thai conservatives would like to believe’ as it has appropriated both Indian Hinduism from the outset of its presence in Siam and Westernization during the reign of Rama VI.

[8] Hardt, 33.

[9] Hardt, 34.

This article originally appeared in e-tcetera.be on May 7, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rathsaran Sireekan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.