Learn how to galvanize an enormous auditorium, tame an usherette and get the best seat in the house at Russia’s principal theater: discover all this and more in an interview with a former claque.

A claque (in French the word means “to clap”) is a person that generates the appearance of success and galvanizes an audience with their overwhelming applause and “Bravo!” types of cheers. Such a position still exists in large theatres today.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, such people were also used to disrupt a performance or heckle a performer. But, according to Konstantin Ilyushchenko, who worked as a claque in the Bolshoi Theater during the waning years of the USSR, today they only liven the audience’s reaction and support the performers.

How did it all begin?

It was the end of the 1980s and I was a young student. There were no computers and I wanted to have fun. I was fascinated by the theatre and once tried to mooch a ticket to the Bolshoi.

I was approached by a middle-aged man who asked me, “Want to come in?” He gave me a ticket and we went inside. He simply liked me – the audience there is mostly gay. I guess I was “picked up.” It turned out that he was one of the claques. We became friends rather quickly.

I had come to Moscow from the depths of Chechnya, so for me, all this cosmopolitan high society seemed magical. Being a part of it appeased my vanity. My new friend told me about the fouetté, the pas de trois, about theatre life and its personalities. He taught me who was good, who was bad. He said that Evgeny Svetlanov was a great conductor, while someone else was a complete non-entity. And I, a 17-year old, was sitting there thinking, “Yeah, that guy is indeed a non-entity.” My head was spinning. I came again. Then I was asked to clap. So I clapped.

Evgeny Svetlanov, chief conductor of the State Symphony Orchestra of the USSR, 1972. Photo Credit Oleg Makarov/RIA Novosti

Was there a signal for the applause?

Our objective was to galvanize the audience. We started applauding and everyone followed. Our work could be heard very clearly when the theatre held “meaningful” performances for military regiments, firemen, and workers – in other words for people who were half asleep.

We dispersed to the various corners of the auditorium and began clapping, knowing the specific places where there needed to be applause. If a ballerina did a fouetté, we clapped and shouted, “Bravo!”

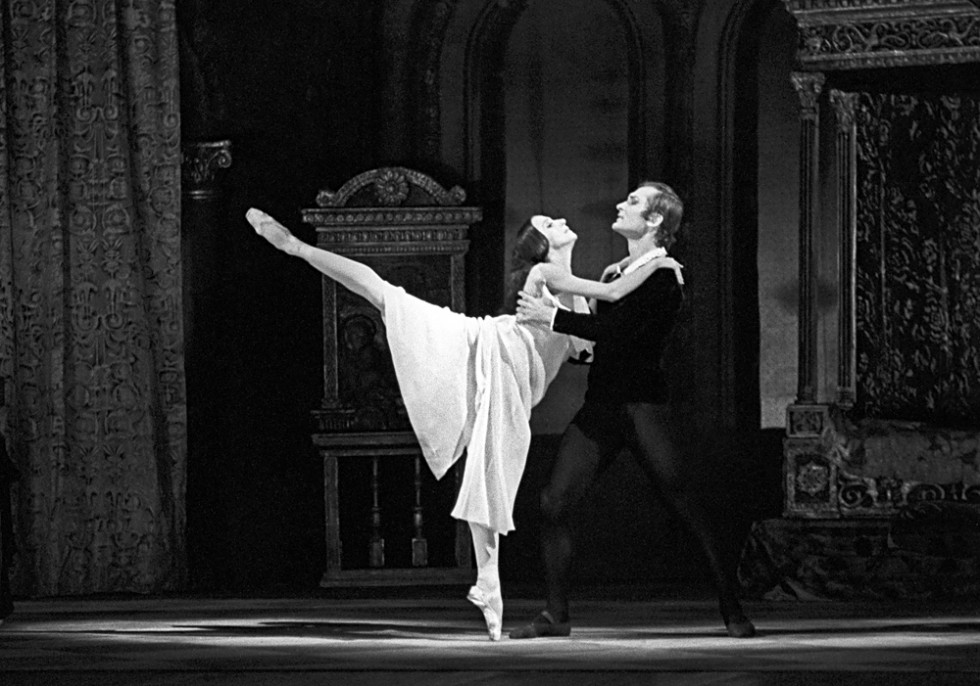

As far as I can remember, we applauded everyone. Back then the primas were Natalia Bessmertnova and Nina Ananiashvili. The principal male dancer then was the former Bolshoi artistic director Sergei Filin, who recently suffered an acid attack on his face. No one was ever booed – this was an invention of the movies.

The audience gives a standing ovation at the Bolshoi Theater, 1964. Photo Credit Yevgeny Kassin/TASS

Who began the claque activity?

This activity was initiated by the highest levels of the theatre’s administration. Back then the principal ballet master was Yuri Grigorovich. He was the one who gave us free passes. I was just a young boy whose aim was not to make money but just to be part of this magical world.

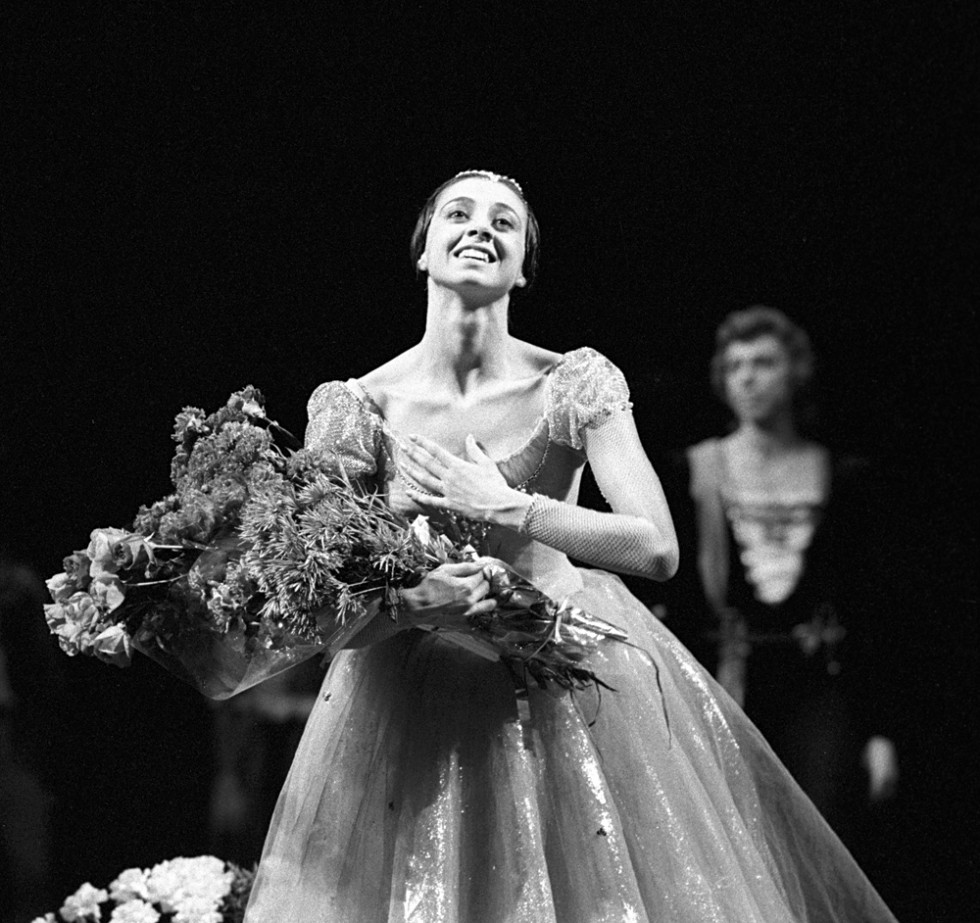

I asked my “mentors” why Grigorovich needed all this, or why Ananiashvili, who danced superbly without the claques, would. I was told that it was a tradition, that everyone wants success, that they want the public to scream and applaud in ecstasy after the performance, to give flowers and that after each fouetté they want to hear “Bravo!” at least three times.

I came to the theatre whenever I wanted to. I quickly formed a relationship with the usherette. This is how the scheme worked: I would always have old tickets, which I would show her, she’d rip them, I came in and during the intermission, I’d come up to her and give her one ruble for each person. It wasn’t a lot of money back then since the average salary was 120 rubles per month. I lived in a communal apartment, had many friends and there were times when I’d bring 10 friends with me.

Natalia Bessmertnova and Mikhail Lavrovsky in Sergey Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet at the Bolshoi Theater. The performance is filmed by German company Teleglob AG and USSR Television, 1976. Photo Credit Alexander Konkov/TASS

In other words, you weren’t paid?

No, I wasn’t. The agreement was that there was a ticket for me at the box office and it cost about 1.8 rubles. You could then sell it for 10-20 times more or even for foreign currency to a foreigner. I even had a certain business plan in my head, which unfortunately I never realized. At that moment foreign currency operations were still banned. And there were instances when I managed to sell the tickets to foreigners on the street.

There was always a sort of industry concerning the tickets. On Saturdays, at a certain time of day, they were sold at the box office. The people jammed their way in; it was actually called a “jam.” They would form a line and spend the night near the box office. Everyone would then be sold a limited number of tickets.

There were serious speculators behind this who would buy the tickets from the people and then resell them for incredible prices. Or they would exchange them in shops for goods. It was a time of complete shortage of everything from food to goods. I once witnessed how in one of the central food stores Bolshoi tickets were exchanged for Bird’s Milk pies.

But I didn’t get a chance to do all this. The Soviet Union ceased to exist and the whole theatrical scene changed drastically.

Nina Ananiashvili after Sergei Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet, 1988. Photo Credit Alexander Makarov/RIA Novosti

Were tickets sold to foreigners near the Bolshoi?

Many yes, right in front of the theatre. I enjoyed selling them in the courtyard of the Pushkin Museum. It is a famous museum, there are always many foreigners there and the place is beautiful.

Once I was taken to a police precinct. The police had seen that I was telling tourists something but could not understand what it was. I had had tickets in my pocket but managed to get rid of them. And my friend, who had been watching me from afar, picked them up. So no loss from this operation.

The Bolshoi Theater in central Moscow, 2016. Photo Credit Reuters

What about the claques? Who were these people?

I think that this was a marginal group of ballet enthusiasts. Usually, they were gay people without families, with average means. And it seemed that for them it was a true delight, thanks to which it was possible to live decently in those days without working anywhere else.

I remember one of them used to say: “I manage the Russian ballet. Some I reject, some I extoll.” I think they were just boasting but still, they believed that they were creating stars.

They could afford certain items that were considered luxurious in the Soviet Union: jeans, VCRs, Sony TVs, but not much else. They did not make money that 19th-century claques would risk their lives for.

One 19th-century claque wrote in their memoirs how his colleague threw himself to stop a runaway horse carriage carrying a prima ballerina. People shouted, “Are you crazy, you could have been trampled to death!” He responded: “My entire livelihood was almost destroyed!”

How many claques did the theatre have in the 1980s-1990s?

In total, the Bolshoi had about 10 such characters – three permanent ones and others like me – temporary students. We were on informal terms with all the stars. I once even heard how they told Nina Ananiashvili that she stretched her leg in the wrong way or that she got up in the wrong place. On the contrary, they also sang her praises. And she accepted it all in a calm and friendly manner. Perhaps it was also good for her.

The main stage of the Bolshoi Theater, 2016. Photo Credit AP

Did you sit in the theatre according to a certain pattern?

As a rule, we would sit up top in the fourth tier of the mezzanine. My favorite spot was near the railing as close as possible to the stage. It was practically impossible to see the decorations from there. But it was the best place to watch the dance. You could see every movement, the orchestra.

Back then the Bolshoi was not very comfortable for the audience. The parterre, yes, it was broad. But from the second row of boxes, you couldn’t see anything.

How long did you do this?

Almost until finishing my studies – more than three years. I remember this because I had seen three traditional Christmas performances of The Nutcracker at the Bolshoi. Then perestroika began and everything started to change – both in the life of the theatre and in mine.

This article was first published in Russia Beyond the Headlines. Reposted with permission of the author. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Oleg Krasnov - Russia Beyond Headlines.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.