Before the war, in what now feels like another lifetime but in reality is just over a year ago, I was in Kyiv, premiering Dash Arts show Songs for Babyn Yar. One evening, our Ukrainian partners handed me an English translation of Anastasia Kosodii and Natalka Vorozhbit’s play Crimea 5am in the hope that we might be able to stage it in the UK.

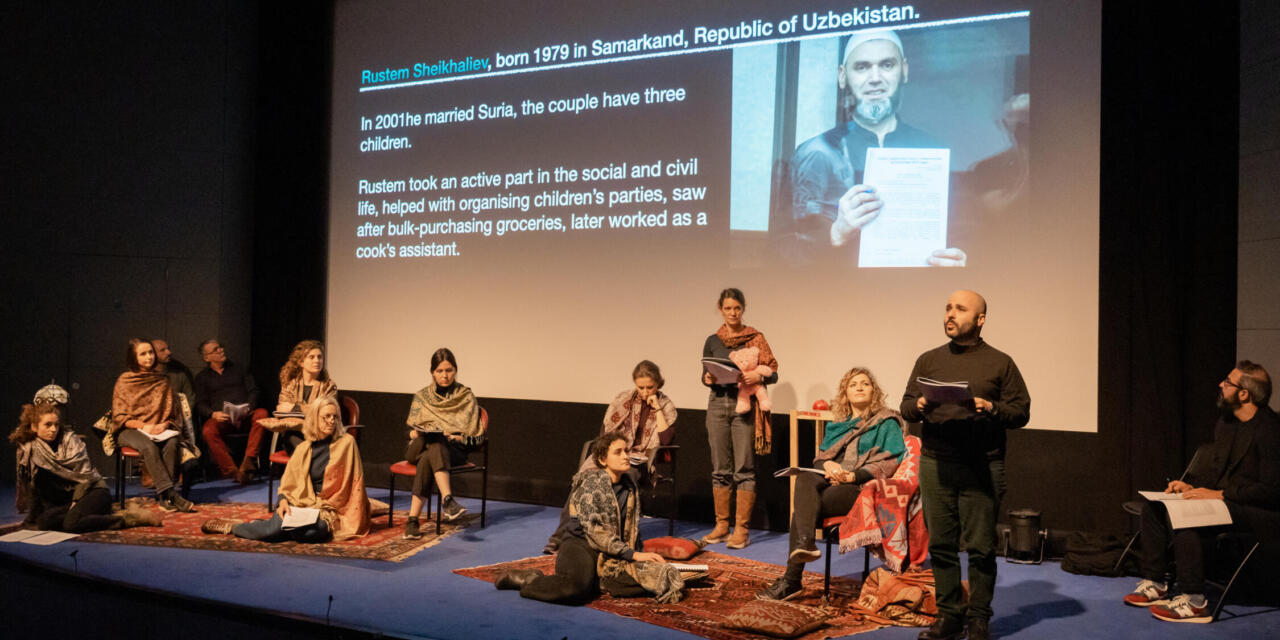

It’s a fascinating complicated piece of theatre, drawn from hours of interviews with the wives of political prisoners in Russian-occupied Crimea, and woven together into a series of chapters which tell the stories of the lives of 10 families today. It features over 40 spoken roles plus a television which also has a speaking role! It’s really not a traditional play.

The writers even acknowledge this in their preface to the text: “It will not resemble a classical stage production, and will be performed as a series of readings without dramatic realism or theatrical techniques. The play will be read by actors and so-called invited moderators, namely artists, civil activists, politicians and public thinkers…. The overall context for the performance should make it abundantly clear that what is presented on stage is not dramatic fiction, but the actual state of affairs in temporarily occupied Crimea.”

I was up for the challenge. The war delayed everything but didn’t repress our desire to make the show happen in London and to tell the stories of what is still happening to Crimean Tatars. In fact, it made the production and its potential impact on audiences more important than ever. Crimea 5am attempts to draw together art and activism, to create a piece of work that is artistically meaningful and moving whilst also challenging how people see the world, shedding light on issues and politics where there is currently little attention. It speaks directly to the heart of Dash’s existence and core beliefs.

So I set off to cast our show – reducing and sharing the 40 roles across 13 individuals, and removing the TV from the script! Crimean Tatars are Turkic speaking peoples and are Sunni Muslim. I was keen to ensure that our cast comprised individuals who hailed from beyond Western Europe and was thrilled to be able to work with a properly international cast of professional actors originally from Ukraine, Turkey, Iraq, Tunisia, Sudan, Romania and Morocco. Their own accents and cultures brought so much texture and richness to the show. And then following Anastasia and Natalka’s request in the script, we reached out to non-actors, to 3 journalists and activists to take the plunge in joining us. We formed a tight ensemble pretty speedily and the cast were so generous in supporting each other and making every member feel comfortable in sometimes difficult spaces.

Together we built our world for Crimea 5am.

I began by introducing a Crimean folk song, Ey, Güzel Qirim, into the room – bringing a musical taste of Crimea which the performers sung as we opened our performance. We learnt and recorded it through the week and the production’s sound designer, Maksym Demydenko wove the recording through the performance. It was beautiful and necessary way to bring Crimean culture and the Tatar language into our English-speaking rehearsal space.

As I had read the script which wove the individual interviews together rather than simply presenting transcripts of an individual woman talking directly to a journalist, I had a distinct experience I was watching a community of women sharing common stories with each other. I wanted to build a simple semblance of a home where these conversations of love and early married life could be shared. And crucially it would only be women within this home. The men, and we do hear from the imprisoned husbands and others, would be conjured up by their wife and only be seen by them. The men were invisible to everyone else. It was a simple and effective form of storytelling, reinforcing the fact that their husbands are now entirely out of plain sight, many of them with sentences of more than 15 years in Russian prisons.

Our projection designer Marie Blunck helped ensure that this reality was ever present – throughout the performance, we projected photographs of the families, their homes, arrests and documentation from the courts. And throughout the week, we had the wonderful privilege to meet on zoom and in real life Crimean Tatars, activists and journalists who are in direct contact with the families themselves. The play was written in 2020. At the time, the men were facing sentences and appealing against them. Now unfortunately almost all of them are serving absurdly long sentences in Russian penal colonies, thousands of miles from Crimea.

The playwright’s request that we avoid dramatic realism and the responsibility of handling verbatim text and representing real lives was constantly present in our conversations in the room. It affected decisions on accents and how to approach stage directions. Should one of our readers cry when the script notes that a voice trembles or they smile through tears? Should we attempt to understand why one of the Russian Investigators appears to ask a fairly innocuous question, free of malice, to a child? The answer to the first question was easier. My suggestion to our readers was that they never quite let go of themselves when they read the script so that they never fully became Elzara Suleimanova or Khalide Bekirova. This held them back emotionally from becoming these individuals but also enabled them to understand the text from their own perspective so that if they themselves were moved by reading the text, any emotion would feel natural. The answer to the second was slightly more nuanced. One of our non-actors felt very strongly that by the act of even exploring the intentions behind a Russian policeman’s words, we are in someways humanising them. These are people, they felt, who had a choice to become a Russian policeman, to perpetrate atrocities and crimes on innocent individuals. They should not be given the slightest opportunity to be recognized as a human being with emotions and even empathy. And yet…. in this context, in Crimea 5am, we were theatre makers attempting to understand others, to attempt to make sense of the world in order to share this understanding with others. The question of intention was to some degree necessary in order to be able to read the text.

This deep tension which is obviously at the heart of documentary theatre – the responsibility to be truthful, and “to present on stage not dramatic fiction, but the actual state of affairs” was most real for me during this conversation. I still haven’t resolved it – I remain absolutely certain that stories should be told and the way that I wish to tell those stories is through the experience of live theatre but I’m truly alive to the responsibilities of telling them with the respect, honesty and truth that they demand.

I look forward to continuing to have these challenging conversations and encounters with important political stories that need to be told.

Trailer film:

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Josephine Burton.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.