Located at the end of a long, narrow corridor, seating the audience near the stage and close to the actors, Trap Door Theatre fosters an intimate viewing experience. With a vintage and relaxed atmosphere, this theater beckons the audience to leave reality behind and enter into a dreamlike state. This particular viewing setting is especially suited to stage a play such as Princess Ivona, one that uses seeming absurdities to critique the faults of our existing outside world. Having read the play beforehand and noted its dark theme, I had prepared myself for a mentally intense night, but I was pleasantly surprised by a truly humorous and, ultimately, hopeful rendition of the play.

Polish playwright Witold Gombrowicz’s 1938 play Princess Ivona tells an intricate but sharp story about the intrinsic mechanism of the socio-political game for power and status. When Prince Phillip decides to marry a girl because of his “repulsion” for her, the unattractive and ordinary Ivona enters the royal family and becomes a variable that disrupts the established order. According to Gombrowicz, Ivona becomes a “decomposing agent” who exposes the hypocrisy and complicity thinly veiled by the glamor of the elite class. Ivona as a character remains silent throughout most of the show. Her silence is imposed by her oppressive environment, but, as the play proceeds, her silence becomes more of a conscious act of protest and subversion. The presence of Ivona brings out the secret insecurities lurking within each royal family member—Prince Phillip (Keith Surney), King Ignatius (Bill Gordon), Queen Ignatius (Manuela Rentea), Lord Chamberlain (Kevin Webb), etc. Threatened by Ivona’s presence and motivated by their personal shame, each member separately devises a murder plan and Ivona ultimately chokes to death on an extravagant plate of fish (pike) served alongside jewels.

Notably, director Jenny Beacraft makes a thoughtful decision to draw attention to Ivona’s only voiced line by having it repeated a total of four times: “it is a wheel…it goes round and round in circles, always, everybody, everything, all the time.” Such repetition–largely reminding us of the avant-garde theater approach–serves to formally register the message that history repeats the pattern in which a scapegoat is blamed to conceal the evils of power. Most importantly, this repetition carves out an emphasized moment for the audience to reflect and self-reflect, calling for fundamental changes in order to truly break free of the cyclical iteration.

Even so, Beacraft presents a “kinder” version of Princess Ivona. Because Gombrowicz utilizes absurdist comedy to expose the hypocrisy and brutality of the power game, he grounds the comedic elements in heavy and dark tones. Beacraft, on the other hand, makes a deliberate effort to temper the intensity and brutality underlying the royal family’s judgment and treatment of Ivona. The cruel intentions behind the sneering and disrespect directed at Ivona are countered by an overtly farcical and, at times, flamboyant acting style.

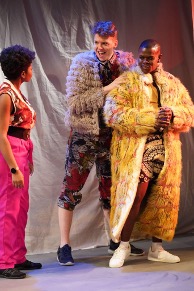

Cat Evans as Isobel, Gus Thomas as Simon, Keith Surney as Prince Phillip.

Beacraft is aware that Ivona’s internal feelings and reactions to the treatment from the royal family are reflective of the immediate feelings and reactions from the audience. Beacraft’s use of farce and flamboyance aims to safely insulate the audience from triggering aspects of the play such as its portrayal of the abuse of women–—so that instead of being taken aback, the audience is drawn to enter a state of “meditation on status, cruelty, and desire,” the central objective of this play in Beacraft’s vision. In this, the production provokes reflection on the wrongs of society and the nature of political games, but also importantly offers a sense of hope and the possibility for healing.

Instead of reducing Ivona to a passive symbol, Beacraft stages Ivona as a multi-dimensional character who experiences moments of genuine joy, laughter, and even tenderness. In staging the royal family members as overtly raucous and sometimes silly, Ivona in turn gains more personal agency.

Laura Nelson as Ivona. Photo courtesy of J. Michael Griggs and provided by Trap Door Theatre.

In one instance of the play, when the prince tries to force Ivona to speak, Ivona, instead of cowering in deference, playfully imitates the physicality and face of an insect, presenting an amusing spin on what would otherwise be a demoralizing moment. Laura Nelson, who plays Ivona, revealed to me that she initially thought that playing the largely silent Ivona would be the least taxing compared with other roles, however, she only discovered that her senses are often overloaded since she cannot utilize her voice, but also this requires her to be extra attentive to her physicality, subtle gestures and dynamic with other characters on stage.

Ivona’s strongest moment of personal agency comes at the end of the play. While the original script only states briefly that Ivona “(chokes)” without shedding additional light on the internal experience of Ivona before her death, in Beacraft’s version, the royal family gather around to observe Ivona caught in a slow-motion twist of agony (in picture). Her death is an emphasized yet punctuated moment. Her facial and physical expressions as she growls and squirms adds a dimension of her defiance to the royal family’s power scheme, unseen in the original script. Ivona’s agency culminates when uses all her strength to jump up and pull down the white curtains, revealing painted red X’s in red square frames posted on the wall. These very curtains are the ones that the royal family previously hid behind to scheme for her death. Ivona’s act of forcefully pulling these curtains serves as a larger metaphor for society that she is stripping away the concealment for the hypocrisy, manipulation and inequality within the existing social structure. The red X’s symbolize both the danger and secrecy of power, and, at the same time, the defiant negation of it. In this way, this final act visually prompts the audience to come to the realization of the true nature behind the masked glory and refinement of the class in power.

Ivona’s agony before death. Photo courtesy of J. Michael Griggs and provided by Trap Door Theatre.

Overall, with a brilliant cast (who are naturally funny) and wonderfully colorful stage designs, Jenny Beacraft’s Princess Ivona offers an unexpectedly tender—thus almost redemptive—rendition that both invites meditation upon and serves to counteract the brutality and darkness intrinsic to the original script. Making the royal family members farcical, ridiculous—almost goofy—characters exposes the irrationality–rather than the simple cruelty–of power. This hopeful mood and aesthetic facade, rather than diluting the gravity of the issues at hand, instead surprisingly lend power and layers to Ivona’s character and, in turn, to the piercing yet simultaneously healing effect of the play’s social critique.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Susanna Sun.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.