Nowadays it seems that it’s the fringe and Off-West End venues that are keeping the spirit of international theatre alive in London. Whereas much mainstream big-name theatre feels increasingly insular, the smaller players are embracing their freedom to experiment by staging work from beyond these shores. A great example is Sergio Blanco’s When You Pass Over My Tomb, translated and adapted by Daniel Goldman; it’s a brilliant meta-theatrical piece about death, loss, love and necrophilia. Like Thebes Land and The Rage of Narcissus — their previous collaborations at the Arcola Theatre — the show is a wonderfully bright mix of storytelling and autofiction.

What are the play’s basic ingredients? Easy. It’s a circular patch of shiny green grass, which could be a Swiss meadow or a London garden, and a bench with a couple of chairs. High above a life-sized dairy cow chews the cud; lower down there are screens which feature quotes about the dead. Three actors arrive and introduce themselves: they are the ghosts of Allel, Danny and Charlie, and they tell us how they died. Weird. Then they assume their characters for the evening: Allel is Me (basically the Franco-Uruguayan playwright and director Sergio Blanco), Danny is the Swiss Doctor Godwin and Charlie plays Khaled, an exiled Iranian medieval scholar.

The plot is taboo-busting and thought-provoking. Blanco, playwright and unreliable narrator, has decided to die with dignity at an assisted suicide centre run by Doctor Godwin in Geneva. He explains the difference between euthanasia (mercy killing by doctors of the terminally ill) and assisted suicide (administered by the patient themselves). As Blanco talks about the attraction of ending his days on the shores of Lake Geneva, he moves the action to Bethlem Hospital in London, a mental hospital where Khaled has been confined after being convicted of necrophilia. Intrigued by his case, Blanco decides to meet him and to donate his body to him after death.

The playwright, who warns us that he will not respect the difference between fact and fiction, argues that, for him, there is not much difference between donating his body to science and gifting it to Khaled, whose love play is described with great tenderness. There is something very compelling about imaging desire at the limits of the acceptable, taking the feeling of the erotic to a place of imagination where few are comfortable. By using the example of necrophilia, Blanco casts a fresh light on familiar subjects such as power relations in a couple, the issue of consent (here given freely, but rarely to those who disturb graves or handle dead bodies) and the contrast between warm flesh and cold bones. The fluid heat of desire meets the finality of the dead person in an act of self-sexuality, whose thrill surely includes its transgressive nature.

As three case studies of necrophiliacs from the past and present are discussed, the intricate mechanics of forbidden sexuality and the fact that such cases pervade world history come into the open. What’s missing is any really challenging material about how the relatives of the various disturbed corpses of the past must have felt, or the sheer horror of assaulting the bodies of newly dead young women. Necrophilia is shown just as solo sex. On the other hand, given that death must come to us all, there is something rather comforting about thinking about how the love of a body might defy the natural end of life, especially as Blanco’s tone is rather light and often charmingly unconfrontational.

Goldman’s translation of the text adapts the story to a London context, and it mixes hilarity with philosophy. There’s a wonderful lightness of touch in the writing which makes the meta-theatrical elements, the direct narration to the audience and the digressions, easy to follow. Although the tone is gentle and funny, especially at the start of the play, there are also pauses for deeper emotion: a story about a child’s death is particularly moving and the details of suicide and of the human body after death are strongly felt. Surreal and unusual incidents include an event which features Richard the Lionheart’s sword — really? Well, what do you expect unreliable storytellers?

What’s fascinating is not just the ease of Blanco’s writing, which integrates meta-theatrical devices with literary examples, which include Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the grave digging scene in Hamlet and the climax of Romeo and Juliet, as well references to terror attacks in Paris, the burning of Notre Dame cathedral and jokes about Adam and Eve (the apple which also features in Snow White). Despite its intellectual range, the play also, quite gradually, quietly suggests that we could all benefit from contemplating our final curtain, and that sexual desire is still the most disruptive and potentially most funny emotion any of us can feel.

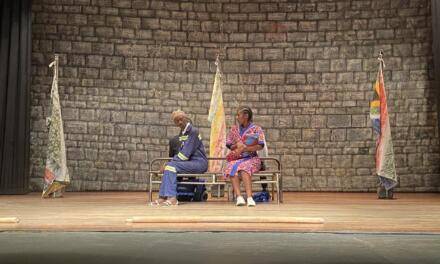

Co-produced with Flying Colours, this English-language premiere is superbly directed by Goldman, with design by Malena Arcucci and video by Richard Williamson, plus excellent performances by Allel Nedjari who gives Blanco both a self-centred confidence (undercut by the humour of his writing) and also suggests his uncertainty in the face of the unknowable. Danny Scheinmann’s Godwin is suitably efficient and correct, while Charlie MacGechan (cast deliberately as an actor who has no Iranian heritage) lends Khaled a slightly sinister sense of erotic transgression. All in all a beautifully chilling exercise in dark humour and meta-theatrical fantasy.

- When You Pass Over My Tomb is at the Arcola Theatre until 2 March.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.