Alberto Conejero’s trajectory as a playwright has been rooted in telling the stories that have lain in the margins, side-lined or erased. He has a remarkable capacity to address that which others have ignored or seen as insignificant. In La piedra oscura/The Dark Stone (2013), Conejero envisaged the final 24 hours of Rafael Rodríguez Rapún, a member of Federico García Lorca’s touring student theatre company La Barraca as well as the celebrated playwright’s former lover, held in a Nationalist prison in 1937 following his capture by Rebel forces. Centring on ideas of legacy, agency, and forgiveness, the play examined the spectre of Lorca that hovers over Rodríguez Rapún – the celebrated writer’s name cannot be uttered in a climate of political fear and social chaos. La geometría del trigo/The Geometry of Wheat (2019) takes as its starting point a whispered tale told to Conejero by his mother: a story of exile, of silence, of lives frustrated and dreams thwarted. El mar. Visión de unos niños que no lo han visto nunca/The Sea. Vision of some children who have never seen it (2022 and still touring) turns to the tale of a schoolteacher murdered by Rebel soldiers at the opening of the Civil War whose values inspired the children he taught. Conejero’s is a theatre forged in forgotten lives.

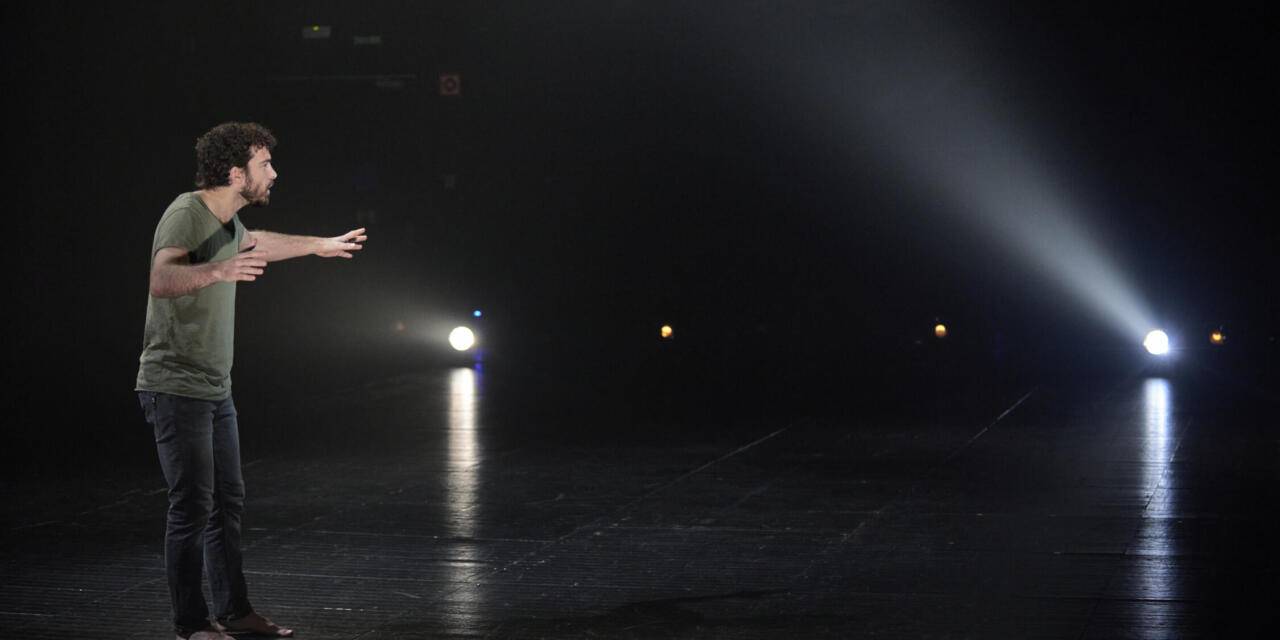

For En mitad de tanto fuego/In the midst of so much fire, Conejero continues this theatrical journey, asking questions of how histories are constructed and given legitimacy. He turns to a secondary figure in Homer’s Iliad, Patroclus, a friend of Achilles since childhood, who meets his death when, disguised as Achilles, the soldier who came to be known as the greatest of Greek warriors, he failed to listen to a command to retreat in conflict and is killed by Hector. His death, narrated in Chapter XVI, lures Achilles back into action, animating Greeks and paving the way for Troy’s demise. For Conejero, however, it is not Achilles who is the narrator of the story but Patroclus, his lover, confidante, and companion. The piece brings a secondary character in the Trojan War to the very fore – an approach reinforced by Xavier Albertí’s lean, minimalist staging and scenography. For while actor Rubén de Eguía is first seen as a shape in the distance, barely discernible in the darkness, he is thrust into the glare with his first lines – delivered at the front of the stage through flashing lights. He appears as spectral figure, reaching out to the audience for something (or someone) that remains forever out of his grasp.

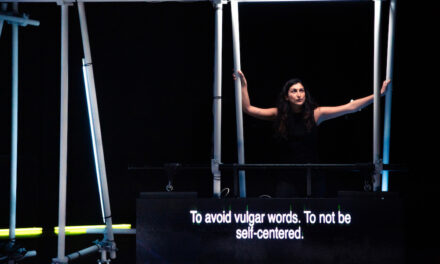

Patroclus is not here to give the audience the story of the Trojan War, rather this is a tale (structured in eight short chapters) of love, desire, flesh and blood, where, as he states, life and death come together. It is a poem of mourning, grief and absence: Achilles is evoked only through words. Patroclus may speak from the dead but is an embodied presence on stage. He makes clear that he is not “here to speak about ‘the most loved of soldiers’ but to rupture the euphemisms, to speak of the insatiable lover”. Patroclus converses from the afterlife, pleading with Achilles to appear, as if trying to conjure him from the darkness. On the large empty stage, Rubén de Eguía’s Patroclus is a lone figure, often surrounded by void: Xavier Albertí and Toni Ubach’s eerie lighting design creates pockets of action while evoking the emptiness of loss. Sidelights illuminate Eguía’s Patroclus from both sides; there is no escape from the surveillance they provide. Patroclus is an anxious figure, he can’t quite believe that the mighty Achilles is with him, recognising the fleeting and fragile nature of all that is special. He is vulnerable and awkward, unsure of who he is or might be. He reflects on Achilles giving his life meaning while ruminating on what immortality means. He addresses the audience directly; he confides in us. At times, he mouths his words, but no sound emerges. When he moves away from the audience, he becomes more animated. He keeps his physical distance, retreating further to the centre-right of the stage, but appears, in losing that physical proximity, to acquire a new clarity and focus. There are moments of exhaustion where he sits, as if reflecting on a life that has escaped him. His body casts shadows on the black wall stage right, a reminder of his spectral presence, perhaps more alive in death than in life. There are times when the lights appear to play tricks on the audience and it is as if he has multiplied before us — the fusing of Patroclus and Achilles in death.

The illusion of the many Patroclus in one. Photo: Pablo Lorente

The lights fade onstage as he chronicles his death, a death foretold in the piece’s opening section. His moves are quick and abrupt, and then there is stillness and quiet. He looks down at his absent corpse — an empty space on the floor — and then moves to inhabit Achilles. It is as if he becomes part of the great warrior. Did Patroclus die for love, he asks? What does it matter, he died. And deaths, in En mitad de tanto fuego, are multiple and terrible. There is no escaping the toll of war. Often it is just numbers, as with the example of 1,000 dying for the love of one man. At other moments, textual insertions plunge the audience into the horrors of the First World War. Repeatedly, the play deviates from The Iliad with snippets of works by Anacreon, Anne Carson, Luis Cernuda, Carmen Conde, W. N. Hodgson, Pedro Lemebel, Lorca, and Sappho (among others) that delineate both the impact and legacy of Homer’s epic poem and the continuing destruction of conflicts that blight communities and cultures. These insertions are slight but significant, they pull the piece in different directions and stretch the Trojan War across centuries to our very present and the current conflict in Gaza.

The play’s two epigraphs signal its intentions. First, that from Simone Weil’s The Iliad, or the Poem of Force:

To respect life in somebody else when you have had to castrate yourself of all yearning for it demands a truly heartbreaking exertion of the powers of generosity. It is impossible to imagine any of Homer’s warriors being capable of such an exertion unless it is that warrior who dwells, in a particular way, at the very center of the poem — I mean Patroclus.

And then that of Paul B. Preciado: that survival involves telling our histories in a different way, dreaming of other possibilities. Both reference the need to tell stories from the perspective of the other, to look again at who is narrating and why, to the importance of providing different ways of saying and doing. It’s something key to Conejero’s gaze.

En mitad de tanto fuego is a play about the art of the possible, the need to question, and the importance of reframing. “There is no more terrible monster than a war hero”, Patroclus laments at the play’s end. Love stories are always ghost stories, he observes at the play’s opening. And this is indeed a piece — both textually and in its staging — haunted by ghosts. There is no music, no score, no props to distract, no décor to focus on beyond the actor’s body: vulnerable, exposed, and alone, but a carrier of different embodied histories. This is a body weighed down by the injustices of history. Words tumble from Rubén de Eguía; they echo around the space, they seduce and they dismay. From what may at first appear a literary text – and I read it before seeing the production — comes a staging filled with rage and fury, compassion and empathy. It’s a tremendous performance from Eguía who holds the stage for 80 compelling minutes.

Rubén de Eguía’s Patroclus. Photo: Pablo Lorente

I saw the production on its final outing at Madrid’s Teatros del Canal where it had enjoyed a sell-out run. At one moment, about eight minutes into the piece, as an onslaught of coughing reverberated across the auditorium, Rubén de Eguía stopped, stepped out of role, addressed the audience, and asked to go off stage to take some water, and return to begin the performance again. It was in so many ways a unique moment, a reminder of our fallibility — and this is a piece about human errors and frailty — of the fact that no performance can ignore disruption, however unintentional, in the auditorium. It becomes part of the performance, and at times — not often but every now and then — the performance needs to begin again. We acknowledge our fragility and then begin again – failing better, as Beckett reminds us. As I write of En mitad de tanto fuego, this incident becomes part of how I have processed the show – a precarious site of humanity, where actor and role are not always one and where sometimes something (maybe the cough, maybe something else) ruptures the fabric of the performance, and the performer has to stop and reset. This was a moment of pure magic in a gripping production where past and present intersect to powerful effect in the retelling of history.

En mitad de tanto fuego/In the midst of so much fire played at the Teatros del Canal Madrid from 25 January to 4 February and is now touring. Future performances include: Sala Verdi Montevideo (16 and 17 February); Alliance Française, Lima (19 and 20 February; Can Massallera, Sant Boi de Llobregat (25 February); Teatre de Lloret, Lloret de Mar (2 March); Teatro Jesús Ibáñez de Matauco, Vitoria (6 March); Teatro del Barrio, Madrid (7-9 March); Teatro Principal, Festival Dferia, Donostia (11 March), Teatro Central, Seville (15-16 March); Teatro Góngora, Córdoba (4 April).

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.