Niko Gorsic is a Slovenian actor, performer, and theater director working under the pseudonym “Nick Upper”. He is also a writer, journalist, editor, and a dance and art critic. In the year 1970, he graduated from the Department of Acting at the Academy for Theater, Film, Radio, and Television in Ljubljana. He was also studying music and art history. He is the creator of ex-Yugoslavian alternative theater. He is an artist-researcher. In the former Republic of Yugoslavia, he initiated the beginnings of the post-dramatic theater. As a theater director and actor, he has performed in 34 foreign states and received 35 awards for his theater achievements.

Ivanka Apostolova Baskar: In 2018 in Macedonia, at the National Theater Anton Panov in Strumica, you, as a guest director, staged the TV screenplay/theater play The Fifth Act by Ljubomir Djurkovic, a playwright from Montenegro. Why did you choose this play, and what motivates you to stage it on the Macedonian theater scene?

Niko Gorsic: Very simple: the actors! In fact, this is my fourth time directing in your country. As a director, I always have twenty to thirty favorite playwrights at a time – and when I see suitable actors, I’ll decide on one of them. Certainly, it is in accordance with the leadership decisions of the theater. In this example, another surprising coincidence occurred, with both actors celebrating their 35th anniversary in the theater – much like the roles in the text by the excellent writer Ljubomir Djurkovic; his text is an up-to-date variant of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov’s play The Swan Song. There is a second reason why. The Strumica theater has been organizing the important festival of chamber theater, Risto Shishkov, for more than twenty years (the festival is named after the famous Macedonian actor). This festival is part of the international theater network NETA; in Macedonia, NETA is coordinated by Blagoja Stefanovski, with whom I have collaborated several times as an actor, director, and expert jury member. (As a first non-Macedonian actor, I also won the Golden Medal for acting by Risto Shishkov Festival). Because of the awards, recognitions, and respect for the Strumica theater, I felt a certain duty to give thanks to this theater. I think with Fifth Act we made a successful acting show. The four awards prove that the performance is something special.

IAB: What is your opinion about the situation and circumstances in our contemporary local and national theater? You are a regular collaborator in Macedonia, as a guest. As a foreign director-actor, what do you notice, what do you like and what is problematic for you about the quality and professionalism within our theater scene?

NG: The biggest problem in culture and art in the context of the new statehood, is the misunderstanding of the nature of the sudden ideological transition from the socialist-Yugoslav system to an entirely different, capitalist system, where initiative is taken by private capital. And it is often unpredictable, foreign capital! There is not the understanding of the responsibility for culture in our new and small states, which were created on the territory of former Yugoslavia – and in all other Eastern European states that have embraced the capitalist system – where culture, art, and language are a matter of national identity and statehood. And because they are small, they can never be put on the market! Otherwise, we will only have consumer culture without art! It is worrisome – especially in the current transition period, which we do not know when it will end – and the cultural policy of the country must remain firm and responsible! The reasonable cultural policy must make it clear that now is precisely the time when foreigners are taking over all economic institutions, and that more funding must be invested in culture, art, and education. Otherwise, you are lost in the market. It is clear that pro-capitalistic cultural policies lead to destruction. Is statehood also failing? All of us who truly believe in our national identity must be aware of the dangers of this new cultural situation. I notice, of course, that the attitude to culture is less pleasant in today’s Northern Macedonia than it was in Yugoslav Macedonia. At that time, the Macedonian theater was highly valued and internationally competitive, as were the Macedonian directors and playwrights. The privatization of theaters in Eastern Europe has proved to be catastrophic for theatrical art: commercial theaters flourish, making art institutions almost non-existent. We all know what Russian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Yugoslav, East German and Romanian theater once meant to the world.

They were an inspiration for Western European theater and art. So, with sensible cultural policy, everything will not be lost. The theater of Northern Macedonia still has vitality and luck, which has not yet disrupted the permanent theater ensembles – so let them remain competitive, specifically in our small states in relation to the large ones.

IAB: As a doyen on the Slovenian and ex-Yugoslavian theater, Niko, please share with us more about the conditions for theater productions back in Yugoslavia, in independent Slovenia, and in Slovenia as part of the European Union?

NG: To answer briefly, it has never been and will never be easy for artists. Of course, the attitude towards theater in all three examples is different. In the former Yugoslavia, a somewhat successful democratic relationship with cultural institutions has developed over the last two decades, where a wide network of theaters with permanent professional acting ensembles and repertoires has been established. Our international festivals were appreciated abroad, as well as our numerous international tours. It also required inventiveness, which came from our competing in the independent theater scene. I remember, in the 1960s, we invented a modern theater that was different from anywhere in the world. I proudly remember the first Slovenian Happenings at the Week of Children Theater, directed by Isok Tori in 1968, where I first performed – not as an actor but as a performer. That was the year when, as a speaker, I was also part of the Ljubljana`s Student Revolution, where we were looking for socialism with a human face, unlike the youth in the West who were looking for human capitalism. It was a happy time in the world that brought about great changes! Unfortunately, things in today’s cultural policy, in the state of Slovenia, are slowly getting worse. The new government still does not know what to do with culture and art in this new ideological situation, when its own economic power has not yet been established and it is waiting for European institutions to address the problem. The EU does not have a culture department and this area is absolutely left to individual states, so they can arrange it as they see it fit. Our countries are unaware that the founders of the EU are the former imperialist states – and that in this field, they must firmly defend their identity, otherwise, we can become European colonies very quickly.

Niko Gorsic. Photo courtesy of Niko Gorsic.

IAB: In Slovenia, how many profiled theaters exist today and how successful are they in the scene? How successful are they at creating an adequate repertoire strategy, performing and staging at international festivals, including the development of international recognitions and relevance?

NG: I have to say, I especially value Slovenian theatrical creativity, which I consider to be among the top in the world. This is shown by the success of various international festivals and the more frequent invitations to exhibitions and directing abroad. The geographical positioning of Slovenia, between Vienna and Venice, was a great asset for our theater and within the former Yugoslavia. We adapted to news faster and shared our achievements at foreign festivals more easily. We made the strongest breakthrough with a very specific political and original postmodern theater in the eighties and nineties, with performances by the Mladinsko Theater from Ljubljana, which was proclaimed European ambassador of culture. Today, National Drama Theaters in Ljubljana and Maribor joined the international theater promotion from Slovenia. For decades, these independent institutions have created vital independent theater groups. It is true that state cultural policy is still trapped in its provincial networks and unaware of our potential in the context of a wider community of European states.

IAB: As a theater director, usually you are staging monodramas, duo-dramas, and chamber theater performances; you are creating intimate performances. You particularly like to collaborate with women actors – why?

NG: I am interested in the role of the actor in theater, which is much easier to achieve in small theatrical forms. There are several such games and forms in ancient literature! I also like to experiment with my puzzle technique. After seven monodramas, some consider me to be a specialist in this type of theater, but all actors and actresses have received international awards for their roles; so far there are twelve. I have also created several successful, so-called spectacle-performances, in Montenegro. There were twelve actresses and only three actors in one play. Actresses, at least for me, are more efficient and precise in their individual projects, which is a consequence of the lack of female roles in world drama texts.

IAB: At this current time, what is happening on the Slovenian theater scene? What do you think about the independent scene; who are the most influential theater artist in Slovenia – actors, directors, and theater managers – that meet your personal criteria?

NG: Those solid, standard productions are still relevant because of the senseless and tragic wars, though more in the remaining former Yugoslav countries than in Slovenia. The post-Yugoslav political theater, which I call the “yellow theater”, further questions the identities of theatrical creators of “mixed marriages”. But it’s provocative for European audiences and it is a real hit internationally! There is very little of that theater in the true spirit of Piscator’s political theater, which dates from European modernism; that is why there are more and more excellent, individual post-poetic performances. With theatrical live art and dance art, we are simply inundated. That’s because of the obviously bad financial situation behind each of these productions. Among other things, we had several well-known, postmodern golden age filmmakers in the 1980s. Nowadays in Slovenia, there is more and more popular among the new theatrical creators of “a new epic theater”, but without the engaged Brechtian politics. It is interesting for global theater festivals. In these settings, they are no longer actors or performers, but storytellers. The range of contemporary Slovenian theater is very wide.

IAB: What are the topics and themes popular among Slovenian playwrights – how courageously are they writing about subjective and objective truths in current society?

NG: That’s the area in Slovenian theater that I’m embarrassed to talk about. Not because of our writers – who I somewhat know well – among them, there are genuine literary pearls in all genres, but because of the attitude of the theaters to them, and the attitude of theater directors who are constantly working abroad. Our playwrights are brutally forgotten. Most of our classical dramas are put on as part of repertoires, while foreign dramas are very popular amongst our contemporary directors. I can say that our playwrights are more interesting internationally than at home. The situation saves the post-dramatic theater, where theater artists collectively “write” about problematic social themes. As a curiosity, I can say that with the new statehood, the number of comedies and satires has rapidly decreased – as if there were more freedom and courage in the previous state.

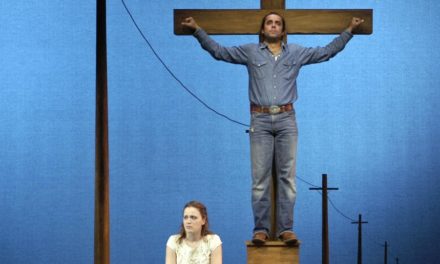

One of Niko Gorsic’s productions. Photo courtesy by Srecko Guncev.

IAB: Do you believe in the effect of political theater in this present time where global, international, regional, national, local politics and conscience are in crisis, identity is in crisis, and the classical left-wing is transforming into the right-wing because of decadence within contemporary, libertarian-leftist thought? It is a time of revolution of power, which together with destructive progress, stimulates and resets the emergence of old-new Nazism and Fascism.

NG: This question requires a thorough answer, but I will share the following simple truth: we must not wait, we must resolutely oppose those tendencies together. It now seems that rich criminals have too many rights, more than the rest of us. Today’s understanding of democracy is corrupted.

IAB: According to your opinion, experiences and intuition, what might be the future of European and Slovenian theaters? What are your plans in the near future, what will you work be at the end of 2019 and what are you preparing for in the year 2020? How do you care and nourish your professional and creative condition?

NG: I will continue to believe that the role of art is the witness, who more accurately detects the truth of our present time than the past, more precisely than any historical textbook. I would usually direct two to three theater plays, play at least one theater role, and maintain my intellectual fitness just like all previous years. Four times a hundred: that is, I will read around a hundred books, watch a hundred theater plays and a hundred films, and visit about a hundred art exhibitions.

IAB: Thank you very much, Mr. Niko Gorsic.

Skopje-Ljubljana, 2019/2020

This interview was conducted and published by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.