Two embarrassing conditions unsettled me at the top of Ellen West, the new opera by Ricky Ian Gordon based on the poem of the same name by Frank Bidart: I had to cough, and I was hungry. The tickle in my throat, which threatened to erupt noisily throughout the prologue, was because I was winded after having run six blocks to make it before curtain to the GK Arts Center, in Brooklyn’s DUMBO, where the opera plays as part of Prototype Festival after its world premiere at Opera Saratoga. The hunger was because I chose to spend the hour before the show making cookie dough instead of having dinner. Both these physical sensations were united in their effect, as illuminated by the perspective of Ellen West herself: the human body is a humiliation.

We know the historic personage of West from her case files. As a young woman in the 1930s, she was treated in a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland for what was not yet called an eating disorder. West confounded her doctors, especially the analyst Ludwig Binswanger, whose notes on her form the basis of Bidart’s 1977 poem, which reconstructs the perspective of both patient and doctor. In Bidart’s verse, the problem facing the patient was a battle between mind, lofty and limitless, and material, mortifying and stultifying. The doctor, though deeply attached to West, faced a more pragmatic problem: a lack of proper tools and language.

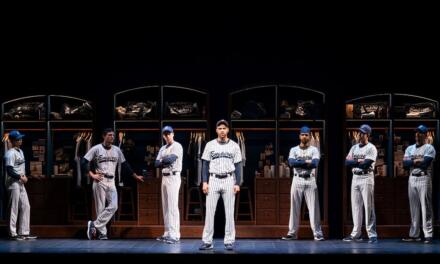

Photo by Maria Baranova.

Gordon’s opera, masterfully directed by Emma Griffin and conducted by Lidiya Yankovskaya, gives equal, dare I say? weight, to both these problems. The role of Ellen West is performed by Jennifer Zetlan with a ferocity that renders her mania at once terrifying and sympathetic. To borrow from the bard, “Though she be but little she is fierce.” Nathan Gunn, in a composite role of Dr. Binswanger, West’s husband, and the poet-figure, is a calming presence, impressive yet fading appropriately to the background in the face of the captivating eponymous character. They are joined onstage by Marla Phelan and Carlo Antonio Villanueva, orderlies whose dancing and other physical movements depict West’s torment. In one particularly effective sequence, West sings about sitting alone at a restaurant, feeling simultaneously disgusted and intrigued, even aroused, as she watches an attractive couple feed each other. At the same time, Phelan sits on a chair downstage, erotically eating prosciutto with her hands.

Kaye Voyce’s simple costume designs evoke a European institution from the early 20th century, yet don’t feel costumey. Ellen’s plain khaki shirt-dress, which becomes a symbol of oppression by physicality, still is lovely, and I could see myself buying it from a Brooklyn boutique that also sells sheepskins and bundles of palo santo. The set design by Laura Jellinek is likewise impactful. The single set spreads out so that we are at once inside Ellen’s quarters at the hospital, in her doctor’s office, and in the corridor; through the window in Ellen’s room, we spy Yankovskaya confidently conducting the small orchestra.

Photo by Maria Baranova.

Ellen West succeeds at a difficult and problematic task: depicting anorexia nervosa with gravitas. Now that awareness of the disorder has seeped into general consciousness, there is a temptation to regard it as a disease of the dangerously superficial, an excess of vanity. It’s a rich girls’ disease; starvation isn’t pathological when you’re poor. Here, however, hunger is an existential struggle and a spiritual pursuit. Ellen West joins the ranks of other great texts about intentional starvation, like Kafka’s The Hunger Artist and Fiona Apple’s Paper Bag.

But there is, of course, a danger in intellectualizing such a disorder. That Ellen dies by suicide is no surprise in the show, and I do not apologize for the spoiler in this review. After all, she is known today because of her disorder and death, not, for example, for the poetry she wrote. We learn that in death, “She looked as she had never looked in life—calm and happy and peaceful.” That is to say, having achieved her goal of ridding herself of a body entirely, she looks satisfied, perhaps like someone after Thanksgiving dinner. Just as Kafka’s hunger artist starved “because I couldn’t find the food I liked,” the poison Ellen ingested was the only meal that suited her taste.

All that being said, I do not charge Gordon with romanticizing anorexia. This is an opera playing to mature audiences, not #thinspo on Instagram. Ellen West doesn’t have to be a cautionary tale to be a tragedy. Like Dr. Binswanger, Frank Bidart and Ricky Ian Gordon before me, I will long be haunted by Ellen West.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.