For the last three years, dance maker and artist Freddie Opoku-Addaie has been a guest programmer at Dance Umbrella festival in London, responsible for the festival’s “Out of the System” strand that questions established structures and presents artists from different local and global cultures and communities. It is a carefully curated program within the festival, weaving together discussion, debate, celebration, and a variety of performance formats. Opoku-Addaie has been a valuable giver and changer of perspective. In his program note introducing this evening’s mixed bill at Bernie Grant Arts Centre in Tottenham, North-East London, he describes the dancer-choreographers who make up the program as travelers navigating many different communities – who also provide “renewable bittersweet fuel” to other cultural travelers traversing complicated local and global landscapes.

The program is well balanced: it partners two solos in the first half and raises the temperature in the second half with a strong duet, followed by a classic piece of Hip Hop Dance Theatre to finish. It feels intimate, aided by the friendly and well-designed modern venue which is tucked away out of sight in a courtyard behind the grand building of Tottenham Town Hall.

THĒO INART. Photo: Miguel Altunaga

The first piece is “Fragility in Man – Part 1” by THĒO INART, a fraught solo for and by Theo TJ Lowe. He alternates between stillness and explosive movement, sitting in a chair, waiting, listening, searching, attacking himself, excavating something from deep within. The space is sparse and contains only a few objects – chairs, lamps, microphones – that could be highly symbolic or purely functional. A jarring soundtrack of spoken words seems to portray a disintegrating mind, painfully fragmented and impenetrable. I am more affected by watching Lowe move than by the piece’s overwrought conceptual framework: each movement is an entity in itself, so powerful that it appears to exist independently, outside of his body. A force with its own presence in the room, passing through him with exquisite clarity.

If Lowe’s solo is an exploration of manhood, the second piece is all woman. Becky Namgauds’ solo “Exhibit F” begins in darkness, with a soft spotlight illuminating a faceless, long-haired, crouching creature. Sounds of running water evoke a mythical forest or a sacred spring where it can come to life and learn to flex its muscles. Namgauds’ bare back, arms and long hair are the expressive centers of a movement language that is primal and animalistic. For much of the piece, she is upside-down, standing on her head or kneeling while manipulating her shoulders, flexing and rotating her torso. The soundtrack of whispers culminates in a beautiful and haunting lament, sung by Yael Claire Shahmoon, as Namgauds covers more space, rolling, falling, tumbling from side to side. In the end, she stands – now fully a woman – and looks back at us before walking away.

Ffion Campbell-Davies and Tyrone Isaac Stuart. Photo: Miguel Altunaga.

The two solos complement each other and are perhaps stronger together than if they stood on their own. One an investigation of the male form, the other a celebration of the instinctual female body, they are connected through their use of partial nudity and their soundscapes of voice and breath. After an interval, the duet “Beyond Words” by Ffion Campbell-Davies and Tyrone Isaac Stuart brings the two worlds – male and female – together. The two dancers emerge balancing on top of each other, walking gingerly out on to the stage. Both in underwear, Campbell-Davies is perched on Stuart’s shoulders while he attempts to walk and at the same time play the saxophone. There is a pleasing awkwardness about the way they continue to sit, stand and balance on various parts of each other’s bodies. Communication between them is never seamless; it requires courage and careful negotiation. At times they seem disconnected, unable to bridge the distances between them. There is a frenetic sequence of trying on different identities in the shape of clothes speedily pulled on all on top of each other. Spoken text about judgement in and by society is strong, but its message and impact get lost partially due to poor sound quality. The overall impression of the piece is one of playfulness, originality and honesty.

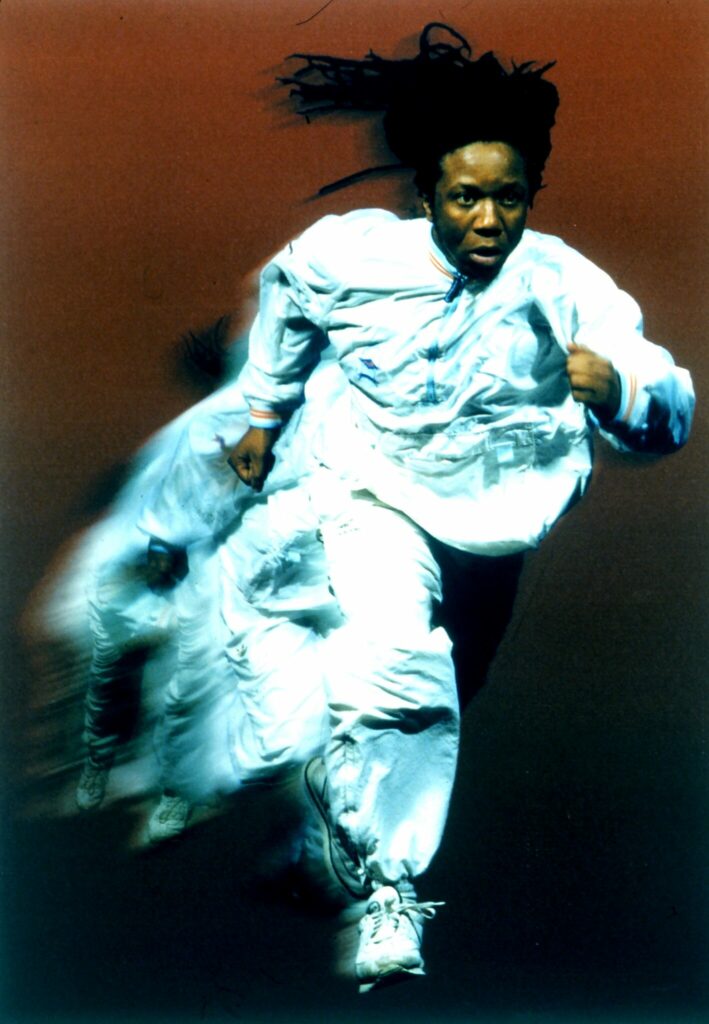

Closing the program is a revival of Jonzi D’s 1995 piece “Aeroplane Man”, a solo about his quest for identity and belonging as a black British man. Told through rhyme, music, movement and snippets of dance forms such as dancehall and bboying, his story takes him from 1970s East London (where he was born but does not feel welcome) to Grenada and Jamaica (lands of his parents), South Africa (land of his ancestors), and New York (land of his Hip Hop heroes). In each place he discovers that he does not fit in and quickly calls up ‘Mr. Airplane Man’ to get him out of there. It is witty, charming and comedic, without losing sight of the struggle and heartache at the heart of his journey. Moved to speak as the audience cheers and applauds him, he says: “It’s such a shame this piece is still resonating. It was meant to be a museum piece by now.” Resonate it does in the Britain of today.

Jonzi D. Photo: Chris Nash.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lisa Marie Bowler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.