What’s the use of thinking about the future?

What’s the use of thinking about the future in a theatre?

Created by the Copenhagen-based theatre company Fix&Foxy, Tue Biering’s one-woman play Land Without Dreams oscillates between these two questions. A woman in a yellow dress stands on an empty stage. She claims to have come from a future utopia where the word “crisis” has lost all its meaning—where death occurs only by choice and technology serves as a common socializer. A future world where there is no poverty, no famine, no polarized politics. But her remarks on this mysterious realm are interspersed with prolonged addresses to the audience, in which she describes a theatrical performance not unlike this one. She takes us through the pasts and futures of a group of audience members who may or may not be among us. Her words alternate between evoking her very own performance and distancing us from it.

There’s more: she punctuates all this by itching aggressively and shedding her skin.

It’s a deceptively simple premise—and a gently gripping one, too, if not entirely consistent. Enticing are the ways in which the Woman appears to perceive and express the audience’s thoughts, simultaneously commenting on her own performance and narrating different scenarios that take us out of the room. From the start, one cannot help but wonder where she is going with these assuredly knowing observations. Her destination becomes somewhat clear as the play concludes by mutating brusquely into an intriguing piece of performance art, involving generous amounts of clay and slime.

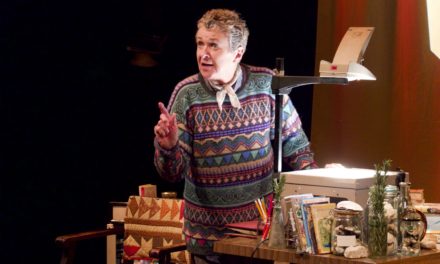

Throughout, Temi Wilkey’s solo performance is revealingly confident and genuine. She delivers even the simplest line with charm and warmth, but always preserving a degree of evasiveness. Especially near the end, when the physical demands of the work turn out to be substantial, her bodily control and dexterity come to the fore. Combined with Lisa Lauenblad’s down-to-earth direction and Janus Jensen’s wraithlike sound design, Wilkey’s hold on our attention ensures that this monochromatic production is only rarely dull. Sophie H. Smith’s free-flowing translation also proves helpful in this regard.

But some things do remain off-balance. The play’s reflexive questioning of the theatre’s role in creating a collective imagination is far more interesting than its engagement with utopian futurity. Why we go to the theatre, what we expect to experience there, and what we do when we go back home are among the questions on which the Woman touches in a deliciously self-aware register. Whenever she shifts gears to the future she has come from, however, there occurs a lapse in tempo and acuity. Whatever is being said about our relationship to the world we inhabit right now and the world we hope to inhabit in the future, it is not incisive enough.

From a wider perspective, this disparity of effect is also at work across the play’s two parts, the latter of which, with its otherworldly visual power, ends up trumping the former. This second part—preceding an awkward coda—is memorably compelling in its grotesque, post-human aesthetic, but its dramaturgical connection with what has come before is not so much ambiguous as undercooked.

The ultimate goal of Tue Biering’s play may be to reorient, or perhaps even upend, our future-obsessed thoughts, but it works much better as a work of performance art that meditates on the theatre from within.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.