Walking out of the spiffy new production of Richard Greenberg’s Take Me Out, my canny friend Tom, who was seeing the play for the first time, offered this quick take: “really interesting, but why in the world did that character Mason Marzac need to be in it?” Anyone with fond memories of Take Me Out’s 2003 New York premiere would find this remark jarring, because Marzac was its biggest treat—a delightfully unguarded, hilariously bravura comic performance by Denis O’Hare that won a Tony. The thought that this character wasn’t needed would never have occurred to anyone back then. Yet Tom’s question made sense, and that has serious implications for the changed profile of this work twenty years later.

Take Me Out dramatizes the fallout when a superstar pro baseball player suddenly comes out as gay at the pinnacle of his career—an event, one hastens to add, that has still never occurred in real life. The player, Darren Lemming, is a mixed-race phenom with strong “crossover” appeal strongly modeled on Derek Jeter and his team, the Empires, is a clone of the Yankees. Lemming is thus so secure in his stardom that he’s Teflon. Publicly untouchable. Or so he imagines.

His teammates, some of whom considered themselves friends, aren’t happy that he failed to inform any of them beforehand. Some complain, for instance, that the clubhouse atmosphere has changed, with carefree towel-snaps at buttocks forever off limits. “We’ve lost a kind of paradise. We see that we are naked,” says his friend and cultured teammate Kippy. Darren’s disclosure was sparked by a bar chat with his best friend, a rival-team player named Davey Battle, who called him aloof (“you’re seen As Through a Glass Darkly”) and pressed him to express his “true nature,” make his “whole self known.” Personal complications metastasize into public disaster and scandal after an openly racist and homophobic young pitcher, Shane Mungitt, joins the Empires.

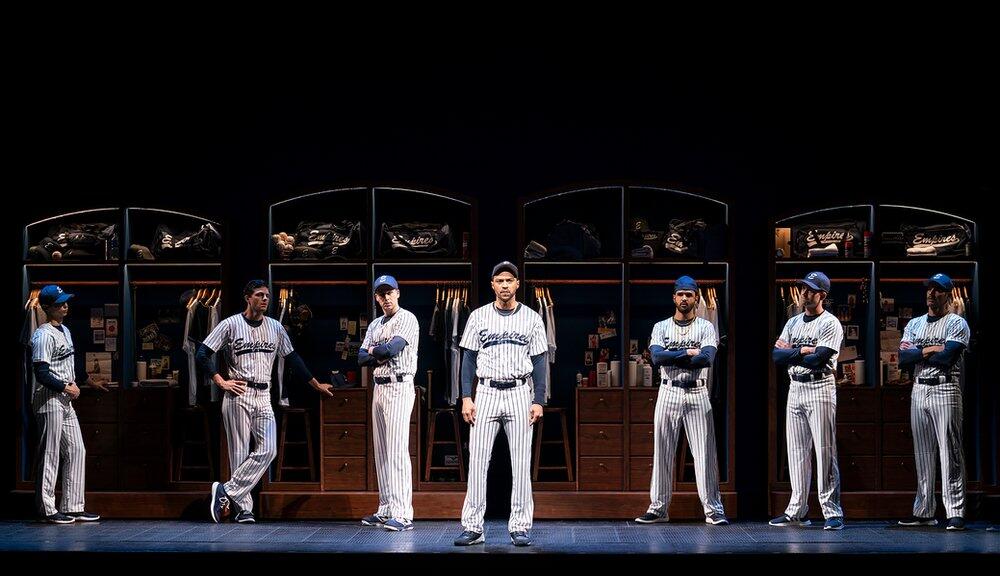

Scott Ellis’s production is tight and strong. Grey’s Anatomy star Jesse Williams is terrific as Darren—low-key witty, affable yet reserved, and even more delightfully direct in imitating Jeter’s mannerisms than Daniel Sunjata was 20 years ago. Brandon J. Dirden also stands out as a ferocious Davey Battle—though Darren’s complete cluelessness about this “best friend’s” virulent religious bigotry always struck me as the play’s biggest plot weakness.

The heart of Take Me Out isn’t in its plot, however, which is often clever but also sometimes far-fetched. Its heart is in the dream the play holds out of mainstream gay acceptance in American society. Football aside, by my lights baseball is still obviously the icon of mainstream America, and Greenberg’s story imagines what an abrupt forced acceptance might look like on the voluntary fields of fandom and friendship, rather than the contentious field of legal rights we’ve grown used to playing on since the Obergefell V. Hodges right-to-marry ruling. Greenberg’s story wouldn’t be moving, though, if it were just a parable about complications from a bombshell. What makes it gripping and delicious is the deep passion for baseball it channels. It even introduces the idea of a specifically gay passion that might conceivably bring bright novelty to the institution. And the source of this passion is Mason Marzac.

Marzac is Lemmings’s money manager—a flamboyantly gay man suddenly assigned to him after his announcement (Darren: “I guess I got you because the guys with families are too distracted”). Mason also happens to be an ace at his job (“In my own little world, I’m you!”). The play’s ostensible narrator is Kippy, ably played with cool insouciance by Patrick J. Adams in the current production. But when trust between Kippy and Darren breaks down due to Kippy’s actions in the Mungitt affair, Mason becomes his main confidante. Mason becomes the savvy gay friend he never had, even restoring his flagging faith in baseball when ugly incidents mount. And because he speaks directly to the audience so much, he essentially becomes the play’s second (and more trusted) narrator.

The crucial difference between Joe Mantello’s 2003 production and Ellis’s current revival is the portrayal of Mason. Back in 2003, Denis O’Hare played him as an extravagantly mannered imp, full of bubbly faux-humble affectations that were infectiously delightful—and, I might add, strongly reminiscent of Richard Greenberg himself. The role struck me as a fascinatingly personal creation—a rare Woody Allenish self-portrait by a writer not given to narcissism. Considering baseball deeply for the first time, O’Hare’s Mason enthused with the zeal of the new convert and made the audience eager fellow travelers on his intellectual mind-trips.

. . . baseball is better than Democracy — or at least than Democracy as it’s practiced in this country — because unlike Democracy, baseball acknowledges loss. While conservatives tell you, leave things alone and no one will lose, and liberals tell you, interfere a lot and no one will lose, baseball says: Someone will lose. Not only says it — insists upon it! So that baseball achieves the tragic vision that Democracy evades. Evades and embodies.

In the current production Mason is played by Jesse Tyler Ferguson as a sensible and practical company man who just happens to be fey and fanciful. Reacting perhaps to the reviewers who dismissed O’Hare’s performance as a gay stereotype (deeply unjust), Ellis and Ferguson went far in the other direction, toning down Mason’s personality so much that he no longer seems particularly perceptive or inspiring. O’Hare’s imaginative rambles were so electric and galvanizing they made you impute all kinds of qualities onto his Mason—artistic flair, investment expertise, talent at friendship. Ferguson’s Mason, by contrast, is so truly humble that his claim to being Darren’s investment counterpart seems absurd, his excurses on baseball rhetorical, and his penchant for digression tiresome. Why indeed, any discerning observer might ask, does the play need a second narrator?

PC: Joan Marcus

My take on this down-to-earth Mason isn’t a mere quibble over personalities. What’s at stake in this character’s performance of gay flamboyance is the very ability of Take Me Out to command a long-term place in the American repertory. This play cannot endure solely based on its topical depictions of institutional shock and celebrity embarrassment, which are already starting to age. Its claim on our national soul must and will depend on the strength of its visionary dream.

This article was originally published by Jonathan Kalb on Apr 10, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.