Mark Bly

Mark Bly is an American dramaturg, editor, and lecturer. He was the chair of the Playwriting Program at the Yale School of Drama from 1992-2004, while being the associate artistic director at the Yale Rep. He taught dramaturgy at Yale and was the director of the MFA Playwriting Program at Hunter College from 2011-2013, and is currently adjunct professor in the MFA Playwriting Program at Fordham/Primary Stages. Over the past thirty-five years, he has served as a dramaturg, director of new play development, and associate artistic director at venues such as the Arena Stage, the Alley Theatre, the Guthrie Theater, the Seattle Rep, theYale Rep and on Broadway, dramaturging and producing over two hundred plays. In 1985, he became the first dramaturg to be credited on a Broadway production when he worked on Execution of Justice written and directed by Emily Mann. Bly has been the dramaturg for the world premieres of plays by Rajiv Joseph, Suzan-Lori Parks, Tim Blake Nelson, Sarah Ruhl, Kenneth Lin, and Moisés Kaufman. He has written for Yale’s Theatre Magazine as contributing editor and advisory editor, TheatreForum, American Theatre, LMDA Review, and contributed to Dramaturgy in American Theater: A Sourcebook (1996), and The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy (2014). He is the editor of Production Notebooks: Theatre in Process (Vol I. 1996, Vol. II. 2001). In 2010 Bly received the Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas’ G.E. Lessing Career Achievement Award. Most recently, he established the Bly LMDA Creative Capacity Grant and Fellowship to fund and support innovative projects furthering the field of dramaturgy. He is currently the resident dramaturg for The Acting Company of New York.

People regard you as the “father of American dramaturgy”. . . .

And if you ask others, they will say that Anne Cattaneo is the “mother of American dramaturgy”! But it is certainly true that until we showed up, production dramaturgy was in a formative state in America.

In the early eighties, the dramaturgical work in American theatre took place largely in the literary office and not in the rehearsal hall. It was literary management and not production dramaturgy. And in the eighties, it was Michael Lupu and my work at the Guthrie Theater that began to open up and define production dramaturgy in America in new ways, and championed the idea of the dramaturg as an artist.

The definition I offered was considered revolutionary in those days: “The dramaturg is that artist, who helps the director and other artists to shape the sociological, textual, directorial, acting and design values that are used for a production.”—Then and today I stand by that definition. Do I achieve that every time? Of course not! But that’s what I aim for as a dramaturg for each time.

In many countries in Europe dramaturgy began with the establishment of publicly funded (national) theatres that chose to create theatre in the community’s native language for the community and about the community. With these theatres the dramaturg arrived. This was the case of the Hamburg National Theatre in 1767, or the National Theatre in London in 1963. How did it all begin in America?

There were many origins perhaps . . . and many false starts too for its beginnings in America.

The position of the literary manager in America began in 1908 with John Corbin at the New Theatre in New York—as the result of the attempt at creating a public theatre. He only lasted there until 1910 reading over two thousand scripts.

There is no question that in the thirties and forties the playwrights/directors George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart served each other as “ghost dramaturgs.” But the dramaturg position never really formally existed in any capacity in the United States until the late sixties. It was the O’Neill Center in Waterford where artistic director Lloyd Richards brought in critics to be dramaturgs on readings of new plays—for their new drama development programme—as he decided that they needed that extra eye.

It didn’t always work, because the playwrights just didn’t trust them, and the critics didn’t know how to talk to theatre-makers: they knew how to give criticism, but had no viable theatrical language. Then, Richards introduced Arthur H. Ballet (the founder of the Advanced Drama Research Program, a theatre worker) to be one of the dramaturgs. He succeeded at the O’Neill Center. Many others followed with varying success. They were not always welcome in the “hallowed circle” with the other artists. But it was the extraordinary Lloyd Richards on a national platform who introduced the potential value of the dramaturg in America in 1969. The actual term “dramaturg” in this role, though, came from the founder of the O’Neill Center, George C. White, who, admittedly, borrowed the idea from Brecht. . . .

What were the other milestones for dramaturgy in America?

Another important stage in the development of the role was at the University of Iowa, where in the seventies, under the leadership of Oscar Brownstein, one of the first dramaturgy courses in the country (alongside Columbia and the Yale School of Drama) was introduced. However, it was never only one evolutionary line; the birth of dramaturgy and production dramaturgy in America was the result of several co-evolutionary paths taken by pioneering dramaturgs scattered geographically across the country.

How did it all begin for you?

I started a BFA in Acting at the North Carolina School of Fine Arts in the late sixties. I worked as an actor but didn’t feel it suited me. Still, I learned a lot that would feed my work as a dramaturg later. I went back to study Shakespeare at Boston College to do a master’s degree. At the same time, I was writing theatre reviews for the local Boston scene, and I realized I wanted to go back to the theatre. I applied to Yale, to study dramatic literature and theatre criticism. In my second year there, Robert Brustein (the founder of the Yale Repertory Theatre) gathered all the MFA students and essentially said: “You are focusing too much on being critics and scholars right now. I want to integrate you more in the life of the school and professional life of the Yale Rep. From now on this is an MFA program in Dramaturgy.”

For me it was great. This meant I was able to work on three professional shows at the Yale Rep as a production dramaturg with major international directors.

This work experience gave me the opportunity to learn the craft from artists such as Ron Daniels (from the Royal Shakespeare Company), Carl Weber (who had been Brecht’s assistant), and work on plays such as the American premiere of Peter Handke’s They Are Dying Out.

Yale played a pioneering part in establishing dramaturgy in American theatre…

There were several waves of the development of dramaturgy in the USA, including the regional theatre movements. There were dramaturgs, who graduated before me (Anne Cattaneo, Michael Feingold, Russell Vandenbroucke, for instance, all from Yale). They did it with and without formal training; they had to learn it on the spot in the trenches.

The formal training of dramaturgs in the USA began at the time when I was studying at Yale, in the seventies. My classmates were, for instance, Janice Paran, (who ended up at the McCarter Theatre and at Sundance Institute Theatre Program) and John Glore (South Coast Rep).

Where did you go after graduation?

I applied to be an associate literary manager at the Arena Stage in Washington. There I was working under Zelda Fichandler, one of the founders of the resident theatre movement in America and who premiered the play The Great White Hope—one might argue helping to launch the careers of James Earl Jones and Jane Alexander. I was there for about one and a half years, but my position was largely one to discover new plays to be produced in the new play festival.

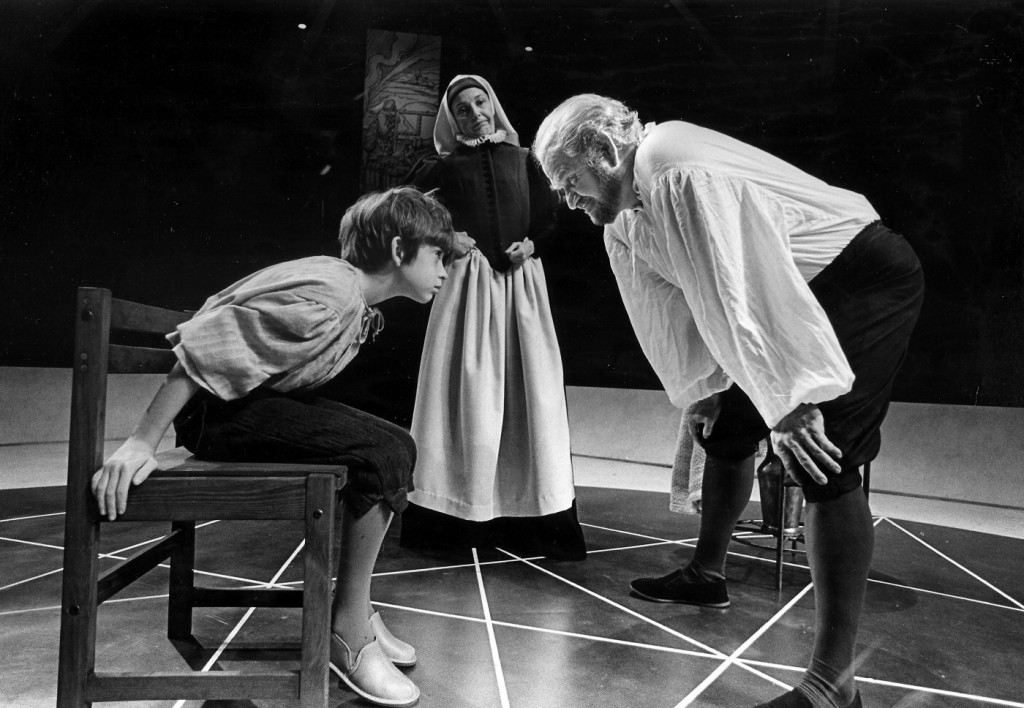

Arena Stage Founding Artistic Director Zelda Fichandler greets the opening night audience and applauds the actors of Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo, which opened Arena Stage’s 30th Anniversary Season in October 1980. Photo: Joan Marcus.

But I have always been a bit of a rebel. I found ways of making myself available to the directors and doing some “guerrilla production dramaturgy” on the sly. I did research but much more by giving notes on the rehearsals and previews and becoming a sounding board for artistic explorations. Zelda found out but she didn’t say too much. Years later, at a national theatre conference, I heard that in speaking to some dramaturgs about the value of the profession Zelda told them that I had brought “dramaturgy to the Arena Stage.”

John Edward Mueller as Andrea Sarti, Hal Wines as Mrs Sarti and Robert Prosky as Galileo Galilei in Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo, which opened Arena Stage’s 30th Anniversary Season in October 1980. Photo: Joe B. Mann.

I will never forget how much Zelda taught me about the value of theatre to our culture, and by example, the kind of notes a dramaturg should give that would be of value. But I was eventually wooed away. In the summer of 1980, I ended up visiting the O’Neill Center in Waterford. There I met playwright/dramaturg Richard Nelson, who told me that he had got a job as dramaturg at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis.

He invited me to work with him as his associate dramaturg. I accepted this offer and left the Arena with the belief that I would have more concrete opportunities to work as a production dramaturg in rehearsals.

For nine years I worked for the Guthrie Theater, first as associate dramaturg, later as head dramaturg, under the artistic directorship of the great Romanian director, and former artistic director of Teatrul Bulandra, Liviu Ciulei. There I had the opportunity to work around such stellar directors as Peter Sellars, Andrei Șerban, Garland Wright, and JoAnne Akalaitis, and actors such as Julianne Moore, Don Cheadle, and David Hyde Pierce.

We had such compelling work happening at the Guthrie. The New York Times, LA Times, and Village Voice critics flew in to review our premieres. I knew we were doing work that was challenging boundaries. But more importantly, other artists, directors, playwrights were flying in to see our work. That was thrilling…

What was the state of American dramaturgy during those times, in the early eighties?

Many dramaturgs were simply functioning as literary managers: they tended to read scripts and do research only. There were good literary managers of course, no doubt that had an impact on the theatre’s programming. But the contribution they made to productions was research oriented largely, and then they disappeared from the rehearsal process. They didn’t sit in rehearsals and give notes, they were not a creative force, they were not considered part of the artistic team.

I was fortunate because the Guthrie’s artistic leadership assumed you would be part of the artistic team. The kind of research I created at the Guthrie was very different from traditional research before then. I did imagistic research, historical research, sociological research and I wrote a long (sometimes even fifteen-, twenty-page-long) letter to the director saying: “Here is the theatrical continuum for this character, this is what I found out about past productions, their interpretations, design, and staging. Here is the research on other translations, other cuttings, here are the major articles that you should read. In order for us to do a meaningful production for our time and place of Molière’s The Misanthrope or Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, we should use these as a starting point for discussion.” And whenever possible, I would always in the letter find a way of putting it in the context of the political situation of our time where we were then. I was always a little subversive, impish in my thoughts. But what was key—was that I was not just handing over endless xeroxes of articles by scholars and critics or images from books—I was translating them into a “theatrical language” that became the ground for the conversation for my working artistic relationship with the director or other artists on the project.

And this was radical! And it came from my training at Yale with Jan Kott (and reading his book, Shakespeare Our Contemporary), and the influence of my mentor, theatre critic Richard Gilman—they both had a major impact on my life as an artist and teacher.

So, in summary, while working at the Guthrie Theater, with Michael Lupu, Romanian dramaturg, we were doing a new kind of dramaturgy rarely done in the United States in those days. We translated the research into theatrical language—and this was rare too in America. Too often the typical gesture in the early years was one of foraging through books and handing piles of academic essays or reviews over. And then expecting the other artists to digest it.

Did you try to articulate your findings in those days?

When I was a student, I read in Yale’s Theater magazine Joel Schechter and Jack Zipes interviewing Peter Stein and Dieter Sturm. Stein and Sturm talked about their primary driving force being the act of questioning “Scheinwissen” or “illusionary knowledge” or received knowledge. I took that away from Yale…

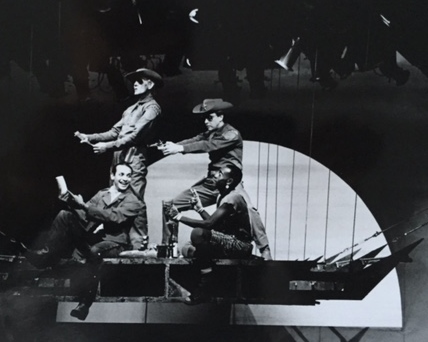

Leon & Lena (and lenz) by Georg Büchner, Guthrie Theater (1987). Director: JoAnne Akalaitis. Dramaturg: Mark Bly.Credits: Jesse Borrego, Don Cheadle, Richard Ooms, and Charles Janasz. Photo: Joe Giannetti.

I was working at the Guthrie when I figured something out. If I was going to matter as a dramaturg, I had to have a questioning spirit. That became my mantra for American dramaturgy: that’s what we have to do, we need to have a questioning spirit! We have to throw away the notion of the in-house critic and the in-house intellectual, who hides away in the literary office and dispenses research; we have to represent ourselves in a radically different way. I also knew that I had to find a way of getting that message out to others in the field. Some people have misread through a surface reading what that means. It does not mean to simply “question.” It means creating an environment where everyone is free to ask questions; where curiosity is at a premium. I listen to the play and other artists and then and only then can I ask meaningful questions.

I was very drawn to the interview format, because I realized that in twenty five-thirty years’ time people would want to know what major artists were thinking when they were doing their work. That would be a primary source. So when I was approached by the editor of Theater, Joel Schechter (a major force in American dramaturgy himself), to write something on the subject of contemporary dramaturgy, I interviewed a number of key people to find out about the state of American dramaturgy. I also wrote an introduction to accompany these interviews. In this essay, I said that the state of dramaturgy in the USA was diverse but it was in danger of dying out. It was slowly becoming irrelevant and that we should stop categorizing or labeling ourselves as the in-house intellectuals, slavishly following the German model. I was critical of how we were “promoting” our profession. And while championing the value of the gesture and the need for it in American Theatre, I questioned how we were practicing it and talking about it.

The introduction and interviews provoked a firestorm in the profession, but they also revitalized the profession by showing the diversity of the practice of dramaturgy in American theatre. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, my introduction and the seven interviews (which also included one about me) underscored that if our profession were to matter or have any value either on an institutional level or in the rehearsal hall, we needed to have a “questioning spirit” present in all our work.

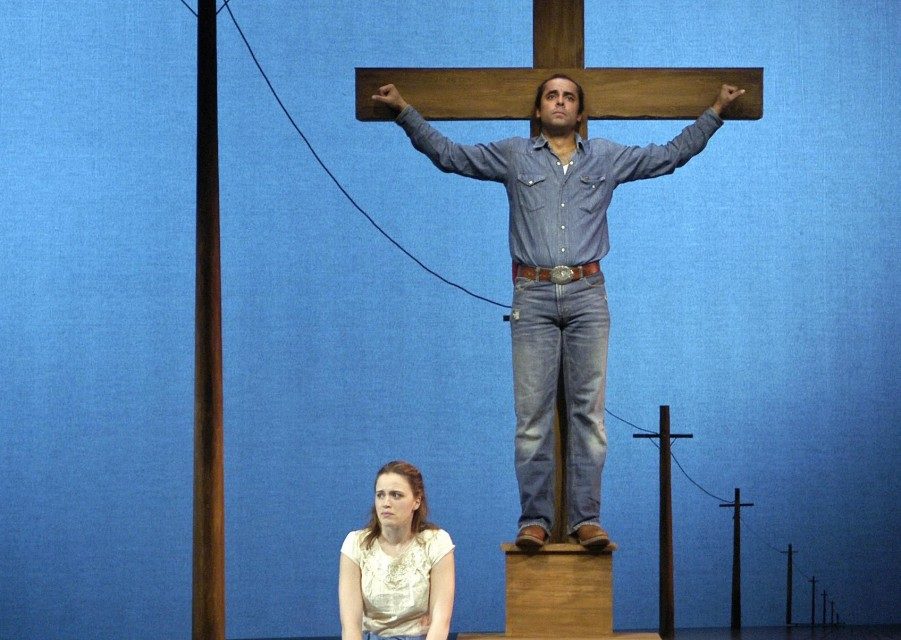

Peter Sellars, director and translator for Hang on to Me, rehearsing at the Guthrie Theater the Maxim Gorky and George & Ira Gershwin musical (1984). Dramaturg: Mark Bly. Photo: courtesy of the Guthrie Theater.

This was published in the Yale’s Theater magazine’s special issue on dramaturgy in 1986.

Interestingly, this issue came out in the same year and the same month when the Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas’ (LMDA) first conference was held in Manhattan at New Dramatists. I was one of the founding progenitors of the organization, and I led several panels at the conference with artists such as Oskar Eustis, Anne Cattaneo, Morgan Jenness and other major dramaturgs of that era.

In 2015, the LMDA is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary. Where did the idea of this organization come from?

In the late seventies-early eighties, there were probably five or six literary managers in New York who came together monthly to discuss the problems and issues of the industry over lunch. At some point, they decided to acknowledge the purpose of these gatherings by forming an organization.

Apart from having a forum to discuss problems, what was the need that brought the LMDA about?

At that time, dramaturgy in the USA was in trouble. There was a need to discuss best practices and how each of us worked; and to meet each other. There had been only a handful of gatherings up to that point, and no national organization uniting us. We lived and worked in geographical and aesthetic isolation. It was time. . . . At that first gathering at New Dramatists there were no dramaturgy guidebooks. There was so much to learn and share.

How did you develop those skills and practices a dramaturg should possess when working in the rehearsal room?

Beyond the Arena Stage at the Guthrie, I learned a lot about how directors work from Liviu Ciulei and Garland Wright. It was an eye opener to find out how Liviu worked: frequently, the starting point for him would be an image. We would work on Twelfth Night and I would collect images for him (from a Fellini or a Bergman film) – and that was far more useful for Liviu than anything else. Because that image became the starting point; the translation from where we would start to develop the mise en scène. We worked on Peer Gynttogether—a five-hour-long production—for nearly a year before it went into the rehearsal room, and then we rehearsed and teched and previewed it for fourteen weeks before it opened!

Peer Gynt by Ibsen at the Guthrie Theater (1983). Director: Liviu Ciulei. Dramaturg: Mark Bly. Credit: Gerry Bamman (as Peer Gynt). Photo credit: Joe Giannetti.

What were your jobs as a dramaturg during that process?

The pre-production work on the text: shaping, cutting etc. I did considerable research (images from travel guides to Norway in the nineteenth century, for instance), helped Rolfe Fjelde and Liviu rewrite the translation; and we also worked with the designer, Santo Loquas to (who later became a designer for Woody Allen), and put together a twenty-four-page commemorative programme.

We worked together very closely before it went into rehearsals, and when the rehearsals started I went in every day. I was constantly sitting there, and Liviu would look at me and ask, “What do you think of this scene?” I was available to offer observations on the acting, directing values, scenic solutions.

Liviu was a true mentor to me. That was exciting and made me grow as a dramaturg. In rehearsal, I would have my research with me that I had prepared, and I would remind Liviu or another director: “this director or actor has done this. . . .” So I would always throw “en guarde” at them, share a challenge but gently.

Directors who worked with us at the Guthrie went away and said to their dramaturgs,“I want you to give me research like, I want you to write letters like this. “But also people would talk about the “Minneapolis Dramaturgy.” Because we were doing something: we were translating research in ways few had done before in America, and we were working closely with the director and other collaborators on a daily basis. Having an artistic impact. And not disappearing.

That triggered debates within the profession about the dramaturg’s objectivity. Some people believed that a dramaturg can only be effective if he/she stays out of the rehearsals, and comes in later like a critic with “total objectivity.” But I believed, “Absolutely not! You can’t have a meaningful artistic impact as a dramaturg, unless you know the source of the subjective choices on all levels.” And that was a huge controversy: the subjective versus the objective dramaturg. Nowadays nobody thinks like this, but back then, in the eighties, that was a hot topic.

There are some major dramaturgs who have emerged as real artistic collaborators in the rehearsal hall over the past couple decades in America and Canada: Robert Blacker, Mame Hunt, Liz Engelman, DD. Kugler, Brian Quirt, Celise Kalke, Lue Douthit, Morgan Jenness, Sydne Mahone and of course, the ones I mentioned before: Janice Paran, John Glore, and Oskar Eustis. And what I find thrilling is that most of these people thirty years later (although they may have producerial activities) are still continuing to work in the profession as dramaturgs!

Caroline Lagerfelt as Arsinoe in The Misanthrope, Guthrie Theater, 1987. Director: Garland Wright. Dramaturg: Mark Bly. Photo: courtesy of the Guthrie Theater.

Were all the directors enthusiastic about your presence in the rehearsal room?

Not at all! For example, in 1984 we did The Entertainer by John Osborne at the Guthrie with a director who had never worked with a dramaturg before. This is a less than first rate play of Osborne’s that became successful largely because the film featured a major performance by Sir Laurence Olivier. When our director arrived, Liviu Ciulei introduced me to him and said, “This is your dramaturg.” The director was gracious. But later he told me, “I never work with a dramaturg!” To overcome the awkwardness of the situation I suggested that we have a drink together. Over libations, I told him, “I tend to work this way, but what would be useful for you?” He said, “I don’t know, just send me something you think would be interesting.” This was a challenge for me! This was a first. I have to admit I felt a little dispirited for a month or so, but I decided I would not lose. I would not be that dramaturg.

I knew the play well, so I went through the reviews of all the major productions I could find and made a chart for the director. I created two columns: the positive observations and the negative observations critics and artists had ever said about the productions. It was a six-page long chart. And I discovered that, in general, the positive criticism said that the scenes set in the music hall were strong, and drew the audience in. Whereas the ones that were set at the main character Archie Rice’s home were less interesting and felt like a kitchen sink realism. I sent this chart to the director—and nothing else. No reams of predictable articles or images to rummage through.

The next time he came to town he said, “Mark, I want to talk to you. I don’t know what a dramaturg does, but I like what you sent me a lot. I have an idea: you know the scenes that are set in the home, let’s get permission from Osborne to set them in the music hall and try to turn this play upside down.” And he added: “I heard that as a student at the University of Minnesota you filled in for your room mate who worked at a very posh strip night club as an assistant to a fire baton/sword twirler. I don’t suppose you could write some extra scenes for the musical hall scenes based on what you know about ‘naughty burlesque’ for Archie and the audience?”

And I wrote those scenes and sent them to John Osborne, he was apparently amused and said, “Go ahead, use them!” And suddenly the whole show became electrified and more farcical and bawdy. We had these “Archie in the audience” scenes and then the director reset several home scenes in the music hall including the climactic one where the family learns that the son has been killed in the Suez Crisis. In many cases, the critics didn’t even notice the changes assuming they were part of Osborne’s play! And the play became a great success.

Were you credited for this work?

Sadly, not. But the director did treat me as a collaborator. But it was a classic example of a dramaturg co-authoring the text and the staging. From this experience, I learned never to give up, even if a director says “I don’t work with dramaturgs,” but to translate the research beyond the paper into something else. That was what I became known for. But much more important than my reputation I began to encourage other dramaturgs to do the same—to “invent” other ways of “winning” than traditional modes of conducting dramaturgy or “behaving” like a dramaturg.

Years later, I wrote an article whose title reflected that spirit or approach when I encouraged dramaturgs (invoking the title of an article by the late Harvard biologist Stephen Jay Gould), to “Bristle with Multiple Possibilities.”

What was next for you after the Guthrie years?

After nine years at the Guthrie, I wanted to do something else: working on new plays. So I went to Seattle Repertory Theatre in 1989 to work with Doug Hughes and Daniel Sullivan, where I learned a great deal about new plays. I also learned a lot from Molly Smith and Moise’s Kaufman at the Arena Stage. They were my mentors. Later I was asked to run the playwriting MFA programme and be associate artistic director of the Yale Rep—and for twelve years I was mentoring major young playwrights, such as Melissa James Gibson, Rolin Jones, Marcus Gardley, Sarah Treem, Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, Kenneth Lin, and Jami O’Brien, and accepted to the program writers such as Tarell Alvin McCraney and Amy Herzog.

How did you utilize and develop your skills as a dramaturg when you moved to new drama development?

The skills I had when working on classics, I was able to deploy at the Seattle Rep when working on new plays. I knew a lot about structure, character etc. I understood a lot about the process: that with a new play, just as with a classic, you descend into a new world, and you have to figure out the laws of that world. I understood that you have to stay back, and can’t say anything until you understand the rules of that world. That you have to listen until “your ears bleed,” and then you are ready to ask questions that truly matter. You can’t prematurely judge the work. Also, I learned that you must do as much research about a new play as a classic.

Back in the Guthrie years, once I asked Liviu Ciulei: “Liviu what is a classic?” And he responded: “Mark, a classic is a classic because it is modern. “This means that you don’t have to do anything to a classic—to make it relevant to give it immediacy—it will truly speak to you here and now. A great play is automatically a classic because, you know, that it has a quality that will make it touch upon people’s lives even in fifty years’ time.

I was one of the first people to whom Tony Kushner’s Angels in America was sent to by the folks at the Mark Taper Forum by Oskar Eustis. And even as I was reading the four hundred and sixty-four pages, I knew at that moment that it would be read and played in fifty years. And not only because of its subject but also, because it was addressing a serious issue about American society: our tendency to polarize in times of crisis.

Part of our job as a dramaturg when we are searching for new plays is to look for those plays that are about these polarizations in our culture and to champion them being done on our stages. Those are the plays that matter: that don’t have immediate solutions. Instead, they ask the audience large, impossible questions.

And when we go into rehearsal with them, we need to be able to wrestle with them. And when the director and the actors ask, “What’s this play about?” we need to be able to say, “That’s why we are working on it, we are all trying to figure it out.”

We don’t have easy answers. That’s not why I’m here. Each of the audience members has to figure that out. That’s the larger mission of theatre. We don’t know the answers to those questions. We are here to discover those on a yearly basis. That is such a privilege. Not an odorous Sisyphean task.

In recent decades, theatre and theatre-making have changed, consequently, dramaturgy (as a response to this) is different. How do you see dramaturgy in the twenty-first century?

The question that we dramaturgs need to ask ourselves is, to paraphrase AmericanCosmos series guru and cosmologist Neil deGrasse Tyson, “How big is our theatrical universe? How big is our dramaturgical universe?”

We can no longer afford to ask the old questions. Theatre no longer can devolve around merely the latest variation on the family drama. Our universe must be larger than that. Our questions must be large public questions about the polarizations of attitudes in our society and world culture. And theatre must be living, breathing, and wrestling at that level.

In terms of stylistic investigations, we can no longer simply afford for the playwright to sit in a lonely room by themselves in front of a screen. Of course, certain plays can be written like that. But it is much more interesting if they come out of that lonely world and create staged events, shall we say, with a group of other artists. And whatever we call those staged events, devised theatre or else, is it not more interesting to explore those possibilities in different ways than we have done it with text in the past?

I don’t think we can afford to have only one way to create that event. It’s just not enough. We can’t do that because the world around us is so much more complex, and we’ll also lose those artists whose mind is much more complex.

Liviu Ciulei at the Guthrie during technical rehearsals used to say to me, “Mark, go next door, there is a wonderful exhibition at the Walker Art Center, don’t stay here at the tech watching us work on this cue over and over.” And I would say, “But Liviu, I should stay here.” And he would say, “No, it’s important that you go next door. You must understand, the Walker is twenty years ahead of theatre; the art museums are ahead of us. You must spend time with those artists too.” And that’s the point. We theatre people for too long have been lagging behind the other media. Not spending time with the other artists. And we need to catch up.

Eric Overmyer, known for such plays as Native Speech and On the Verge and Emmy Award-winning series such as The Wire and Treme, some twenty years ago in an interview with the New York Times aired his frustration with the American stage: “Playwriting is an antique, an arcane avocation like archery or clog dancing.”

With all due respect to the art of clog dancing, American theatre can’t afford to be as antique as clog dancing or behave that way! So we need to release from that in terms of content and in terms of stylistic investigations and new forms.

Where do you see the dramaturg’s role in that?

The dramaturgs are the scouts. We need to be scouts, dramaturgical Voyagers 1 and 2, out there beyond in the unknown: beyond the heliosphere and Oort Cloud looking, looking, looking. We may be alone occasionally but we need to be out exploring. We mustn’t be afraid. We must report back. No matter how feeble that signal, we must send back a signal.

![Mark Bly with the Bly Fellows [l-r]: Jessica Grindstaff, Janice Paran, Lydia Garcia, Mark Bly, Philippa Kelly, Katalin Trencsényi, Heidi Taylor and Jan Derbyshire at the LMDA 30th anniversary conference, New York, Columbia University, 2015. Photo: Cynthia SoRelle.](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/11_Bly-Fellows-1024x768.jpg)

Mark Bly with the Bly Fellows [l-r]: Jessica Grindstaff, Janice Paran, Lydia Garcia, Mark Bly, Philippa Kelly, Katalin Trencsényi, Heidi Taylor and Jan Derbyshire at the LMDA 30th anniversary conference, New York, Columbia University, 2015. Photo: Cynthia SoRelle.

I never had a master plan. I learned along the way, mostly because I’m a good listener. I always stay back and listen to what people need. I learnt in many ways, the job is teaching you. I knew what dramaturgs needed because I knew what I didn’t get: tools to use in the rehearsal space; ways of translating the research for the other artists to deploy. So when I have taught playwrights and dramaturgs—whether at Yale, the University of Houston, Hunter College, or currently as a Playwriting Professor in the MFA Program at Fordham/Primary Stages or in my work with actors at The Acting Company giving them my Production Notebooks research—my aim is to share work that will offer the unexpected.

I like filtering research through a new prism from other disciplines. This allows new plays to become something more; and playwrights respond to that immediately.

I believe in being a polymath: not just a dramaturg, but an art historian, an amateur scientist, a playwright at remove, a mathematician, a historian, a paleontologist. For instance, I also have a strong and serious interest in science. Many of my articles are filled with art and science, and through them I would like to believe I created new dramaturgical paradigms, altered the American dramaturgical community’s thinking, and helped people think in new ways about the dramaturgical gesture.

In 1992, when I was asked to write “Bristling with Multiple Possibilities” (printed in the compilation, Dramaturgy in American Theater), the whole notion behind that was to celebrate the idea of this principle. This goes back to my definition of the dramaturg as a person who must help the director to shape the sociological, textual, design, acting and directing values of the production. I may not be a director but I know some things about directing, I may not be a designer but I know some things about being a designer. I echo the Darwinian creative principle of redundancy in my work, and that makes me a better dramaturg; one that can have an impact on all levels.

This is similar to the two for one principle in evolution: the nose—it breathes and it smells; the mouth—it breathes, but it also helps you stay alive through eating food. That’s what a dramaturg does. We must celebrate our redundancy and must “bristle with multiple possibilities” and not accept one role as simply the person who supplies “research” in a conventional reductive manner.

You may be familiar with Terry McCabe’s infamous article, “A Good Director Doesn’t Need a Dramaturg.” What would you respond to that argument?

The greatest directors are voracious and hungry to work with great artists. And that’s what a first rate dramaturg does: they just keep putting more and more into the equation and enriching and deepening the stage experience for everyone. What would possess one to exclude such a “catalyst” from the theatrical equation? That is the real mystery.

(Boston, 28 and 29 June 2014)

Katalin Trencsényi

Katalin Trencsényi is a London-based dramaturg and associate lecturer at RADA. She is the author of Dramaturgy in the Making. A User’s Guide for Theatre Practitioners (Bloomsbury, 2015), and co-editor of New Dramaturgy: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice (Bloomsbury, 2014).

This article was originally published on Critical-Stages.org. Reposted with permission of the authors. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katalin Trencsényi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.