A Poem About the Unknown is a dance theatre performance directed by Chinese dance artists Lian Guodong and Lei Yan with the participation of an international creative team. Co-produced by partners from China, Germany, and Italy, the performance was scheduled to premiere in 2020 – and, against all odds, it managed to do so. In this conversation recorded in October 2020, the play’s dramaturg Kai Tuchmann and producer Fabrizio Massini discuss the challenges (as well as the rewards) of creating a piece addressing humanity’s future during a time (the Covid-19 pandemic) where all points of reference seem to crumble.

Fabrizio Massini: Let’s start with your role. You have worked in many capacities: director, teacher and, as in this project, dramaturg. Can you describe in your words what’s a dramaturg’s main task generally, and in this specific project?

Kai Tuchmann: When people ask me what a dramaturg is, I mostly fight against one prejudice. People always believe dramaturgs are the guys who structure plays according to an existing set of rules. But, according to my understanding of dramaturgy, I try to emphasize that theater is always something that is happening right in the moment. Theatre is a practice confronting a reality that is basically born out of a constant flux of new circumstances and challenges. And when we engage with such a reality, we cannot only refer to a stable, already existing set of rules to structure this reality. Thus, I think a crucial aspect of dramaturgical practice lies in answering the question: “How to create a performance in the absence of rules?”. You could say dramaturgy is a practice of ‘thinking as you do’, and doing as you consider the possibility of how to make performances in the absence of rules.

FM: That sounds conceptually and theoretically solid, but how does it translate into practice? Can you give us some practical references?

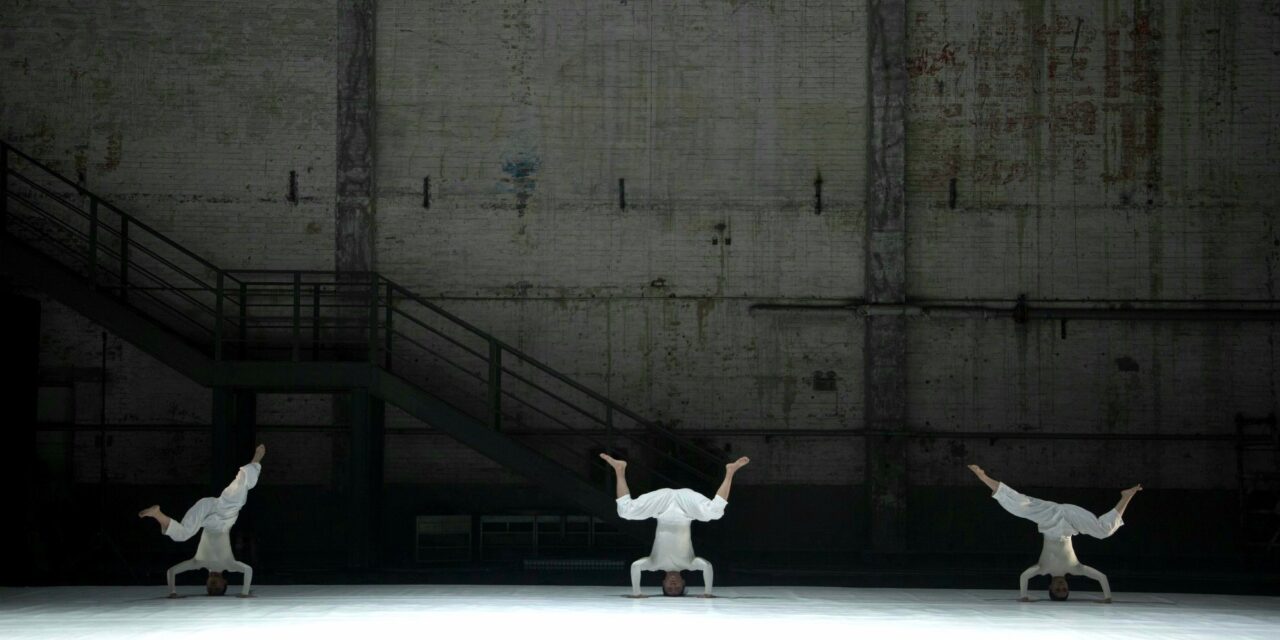

Photo by Feng Yuehong

KT: I think it is part of the dramaturgical job to always reflect on the performance situation, which touches upon issues such as: who meets whom? When? Where? And: how does a performance interact with already existing public spheres? I think that especially now, in this time of the pandemic, questions such as “what is performance? How is the situation, the physical situation of performance situated?” have been raised to a very urgent status. Because now we don’t have any certainty anymore. The notion of “performance situation” has radically opened up. What happens to the idea of “proximity” in a context where online-streaming, VR Theatre, or Zoom Interfaces are becoming an integral part of theatrical business? How is this impacting our understanding of co-presence? Of performance? Of liveness? What is realness? There seem to be no certainties anymore, so it’s a perfect time for dramaturgs.

FM: Let’s frame these general reflections within our own, specific context: the making of A Poem About the Unknown. Can you say something about the very start of the process?

KT: When I was introduced to Guodong (the co-director) he was thinking about making A Poem About the Unknown a reflection on how technology intersects with society and art. I thought it was a very intriguing conversation, and being offered to join was very appealing. Because to me, who engage a lot with real on-stage events and with the reality of memories and realities of the body on stage, this concept related to my work in China throughout the last years. This project suggested a new direction of research and work. Engagement with the implications of technology and media was a trajectory that I longed for, and that I wanted to take. So I was quite lucky to be involved in this conversation, and it became the starting point of a new topic I wanted to work on.

FM: This time of pandemic has been, and still is, a special time for everyone. That is true for dramaturgs and for dramaturgy as a concept too. In 2020 we saw many artistic attempts to elaborate and narrate the pandemic, and probably in 2021, we will see more of them. How do you think the pandemic impacted A Poem About the Unknown, and to which extent this work is understandable as a response to the pandemic?

KT: Our specific way to engage with the pandemic, for myself and the whole crew of A Poem, is still an open question. I feel that right now, in the middle of the production, we are still in the process of digesting the changes that this pandemic brought to the original artistic plan. We are digesting what this pandemic has brought to each of our individual lives, we must cope with lockdown and all that. And I perceive that, for a long time, we have been very receptive. However, in the last weeks of the production, we started a proactive approach regarding these immense changes that have occurred in our lives and our artistic planning. Slowly the experiences of the last months are getting material right now. I think this process has just started; it is hard to give definite answers at this stage of the process.

Photo by Wu Shi

As I said before: there’s an absence of rules, an absence of know-how for dealing with a situation like this. So one of the biggest joys is to dive into this “absence of recipes” on how to make art in such times. One of the ways that we try to think was to look back in history, revisiting the texts of Artaud, who was a theater maker like us, who dreamt about the pandemic (the plague) to come, about restructuring art and society. Of course, he conceived this pandemic quite differently from the real one that is happening now. But this journey back in time is one way we tried to navigate this “inherited’ life”; to get into a dialogue with those who came before us, who wrote manifestos and texts about the pandemic, about the situation of the artists in challenging times, people that wrote texts about technology. And I think our rehearsal is very much about establishing a dialogue with these old accounts from the past; by revisiting these old texts we hope to arrive at our own Poem.

FM: I agree with your point of engaging in this exercise, to ‘adjusting the rules of the game as we go’, to adapt our working principles onto what is actually in front of us, instead of following prescriptive models. But, on the other hand, we still need a compass to guide ourselves in the chaos. If we consider our original intention as such compass, then I think such intention can be formulated as: let us put aside all the (mainstream) dystopic reading of the future and, instead, let us cast a “positive glance” full of curiosity towards the future. Can you talk a little bit about that? Did we manage to stick to this predicament while, all around us, the pandemic kept spreading?

Photo by Feng Yuehong

KT: I think this is a very crucial point. Since the very beginning, part of our intention was to investigate the implications of technology, how technology is impacting society. And we are witnessing this curious phenomenon: there are always two factions taking sides. On the one hand, you have the “radical techno-pessimists” that see no connection at all between media and human beings and are convinced that digital technology will bring about the doom of humanism. On the other hand, you have people claiming that in five years or so it will appear a complete Artificial Intelligence which will transcend into a new entity; this kind of reasoning usually crystallizes around Artificial Intelligence, so I got used to call it “future bullshit of AI”. Both these thinking and discourses are very much interwoven with political and social agendas. Naturally the “future bullshit of AI” front wants to sell commodities, they want to repeat “AI” thousands of times to create a market for whatever they have ready in the pipeline, down in Silicon Valley or in Zhongguancun (Beijing) or in Bangalore. While the “techno-pessimist” front, like the nationalists of our time, are people that simply cannot deal with change.

What’s very interesting to me is the space in between these two fronts. Could A Poem About the Unknown become another way to talk about technology? Could it contribute to a more realistic assessment of our engagement with technology? These are exciting and significant questions, not least because technology has become the very method in which we execute the production. We are having this interview now on Zoom, we do creative meetings on WeChat, we exchange physical exercises and rehearsals as data files on Google Drive or Dropbox, through virtual representations of ourselves. This is very real, and it is neither the “decay of human being” nor the “advent of Artificial Intelligence era”: it is just what we are practically doing.

FM: Do you think that it was during this search for a more “realistic” approach, that the figures from our past appeared?

KT: Yes. We are engaged in a dialogue with people who had strong visions about the intersection of art, society, and technology. Like Artaud, John Perry Barlow (author of the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace), and others. During this time of the pandemic, when we have become so dependent on technology as an extension of our creativity and humanity, it is very interesting to engage with these texts from the past.

Photo by Feng Yuehong

FM: As of right now, do you think this dialogue has led us to any “core” of our artistic process?

KT: If there was a core belief, I would say it would be the following: any media is an extension of man, of the human being. A pencil, a chair, a car, a smartphone, a computer, an algorithm: all of them can play the function of extending our being, our creativity, our passions. Nothing is good or bad in itself, nothing relates to the discourse of “techno-pessimism” or “future bullshit” per se. It is about how we define the meaning of the media that we use. You could cut it short and say: every media is a poem. It is a poem about the Unknown because we don’t know right now what all this Zoom and this so-called Artificial Intelligence are about to bring. This is Unknown, it is still in the making. But it is us who have a say in what the meaning of technology will be. This is so important to remember because, polarized between the “decay of mankind” and the “advent of the new man”, we totally forgot our agency in defining technology and media. And I think that is our core intention.

FM: Would you say that this new mode of communication and co-creation, forced by the limits imposed by Covid-19, has brought you any insight? Except for a push to find creative ways to continue this project, did these past months give you new insights on our job as theater practitioners, something that you haven’t realized before?

KT: This working methodology has made me aware of the good things distance can produce. Before it was normal to attend several hours’ long rehearsal, watch a concoction of random materials whose overall meaning was unclear to everyone, and then piece it together into an intelligible whole. Now, this is not possible. We are forced to structure our working process much more, the things we communicate to each other need to be more precise. This time and situation have brought about a need for a structure that I find quite interesting. Also, the flowing of time has changed. Before it was common to develop a kind of “production blindness” during rehearsals because you are “locked” in a room together for weeks on end until the countdown to the premiere kicks in and forces you to finalize everything. In those situations, taking a step back was impossible or very hard. Instead, in the past months, we have been meeting one or two times a week, so we had big gaps in between rehearsals. These gaps are filled with reality, changes, new thoughts, with the possibilities to revising earlier conceptual ideas and materials. This is something new that I appreciated.

FM: Isn’t that a bit too much “half-full glass” thinking? It almost sounds like we should be glad for this situation!

KT: Of course not! This period has certainly made me aware of how much I miss the immediate contact and the proximity, like non-verb communication, the way everyone relates to each other, the way we establish intimate connections. This process has shown me how sad this lack of intimate communication is, but it has also made me aware that this new mode of communication facilitates a more generous way of spending time with the project. Maybe in the weeks to come, we can reflect on how to make a good combination of these aspects, how to reconcile them, to make it even better.

Photo by Feng Yuehong

A Poem About the Unknown premiered on October 30th, 2020 in Beijing at the Name of the Rose (798 Art District) and restaged on November 13th 2020 in Shanghai at the Shanghai International Dance Center theatre. Touring in Europe is planned for 2021 (exact dates to be announced).

CREDITS

Director/Choreographer: Lian Guodong, Lei Yan (L-Square Performance)

Performers: Fan Lu, Qian Tingting, Xu Yiming

Light design: Wang Jingjing

Sound design: Letizia Renzini

Visual design: Qiu Yu

Costumes: Zhang Sisi

Video/Photos: Fan Cong

Dramaturg: Kai Tuchmann

Producer: Fabrizio Massini

Assistant Producer: Xu Li

Commissioned by: YAP – Young Artist Platform for Dance (China)

Co-producers: Fabbrica Europa(Italy), Goethe-Institut China / International Coproduction Fund, Theater im Pumpenhaus Münster (Germany), Shanghai International Dance Center Theater (China)

Supported by: Beijing 9 Contemporary Dance Theatre

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Shiya Lu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.