(A Lecture-Essay Hesitantly Affirming the Idea that Every Lecture is Also a Performance)[1]With the exception of the introduction and the preamble, this text restates my farewell lecture at P.A.R.T.S., delivered April 26, 2022. I’ve been teaching theory classes at P.A.R.T.S. from the … Continue reading

0. (MOTTO)

Thinking or writing would count for nothing if it didn’t at times produce some limited degree of understandability – of the potential to understand without the realization of any particular understanding. The same goes for the making of art, in whatever medium, and the art of dancing, acting, or playing music.

1. (ON THINKING AND THEORIZING)

Let’s start with some distinctions. In What is Philosophy?, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari suggest that there are three modes of thinking. There’s thinking with and through concepts, existing or newly invented: that’s theorizing. There’s thinking with and through formal elements (such as numbers) by means of abstract operations (such as subtracting or squaring), the net result being empirically testable formal models: that’s indeed science. And there’s thinking in and through percepts and affects, in and through “the sensible”: that happens in the arts.

There is thus thinking in general, with or without words, visually or discursively, or even bodily; and there’s the more particular mode of thinking called theorizing. Thinking changes into theorizing with and through explicit conceptualization, or the deliberate forging of more general notions and definitions that abstract from particular phenomena.

A theory is a self-referential network of concepts in which concepts refer to concepts. A grand theory is a conceptual network covering all relevant phenomena. It’s a conceptual simulacrum; it reconstructs everything that is relevant for the theory in its own conceptual terms.

Most art theories are rather limited conceptual networks fitting a restrained collection of artistic phenomena by negating many others. They are not encompassing but selective. This is not a shortcoming, only a restriction – albeit one that should be acknowledged. Beware of essays or reviews that start with a sentence like “contemporary dance shows a marked tendency to (etcetera).” That kind of statement is always about a specific niche that is considered paradigmatic for reasons that are, as a rule, not explicitly articulated.

2. (ON THEORY AND DANCING)

Theory often claims enlightenment: the theorist knows what the theorised do not know. However, dancers do know what they do – they just do it unknowingly from the point of view of theory. The dancer’s knowledge therefore has a paradoxical character: it resembles what Giorgio Agamben in another context terms “knowledge that is not known,” knowledge “that does not have a subject and can only be recognized.”[2]Giorgio Agamben, Taste. London: Seagull Press, 2017, p. 63. The dancer is knowledgeable, and for sure not only physical – but “dancerly.” She enacts or practices an implicit knowhow – a non-discursive knowing-how-to-go-on. Often that knowhow is called intuition, yet that word precisely indicates a knowing that is not able to know itself.

Dance is thought, always. The dancer is a thinker, always. There’s thinking in the doing. The dancer doesn’t think conceptually or formally when moving, but using unreflexive movement, moves thoughtfully. To think as a block of moving sensations is to dance the dance as dancer – at least when one tries to conceptualise this activity.

3. (ON THE NOTION OF ART/DANCE)

Is, for instance, eating a pear on a stage a dance work? The question is ontologically undecidable because “dance,” just like “art,” is a performative notion. A dance work only exists as such when it is observed as such: one names – or doesn’t name – the eating of a pear on stage a work of dance (and one indeed names with more or less symbolic power).

However, the real lesson of conceptual art is that art is not only a performative but also a moral notion. Saying “this is an artwork” – and even more so, saying “this is an interesting artwork” – equals saying “it’s worthwhile,” “it deserves respect.”

Most art critics and art theorists practice some form of art ethics. What (who) should we respect, what (who) not? – that’s in the end what the struggle for symbolic recognition or, in Pierre Bourdieu’s terms, the endless quarrel over legitimate and illegitimate works is about.[3]See, for example, Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford (Cal.): Stanford University Press, 1996.

4. (ON TEACHING THEORY IN ART SCHOOLS)

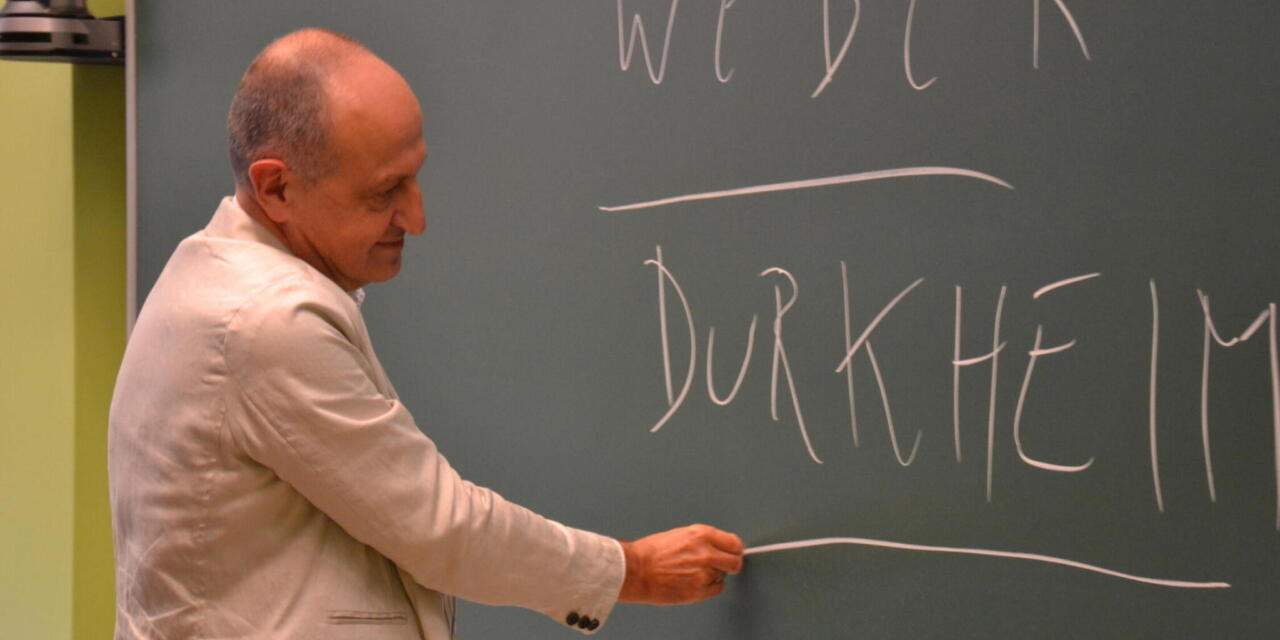

Teaching theory involves different things: be a voice of others, trying to find now and then your own voice, and creating a climate that facilitates the students’ voicing back. It’s about thinking and, quantitatively more important, it is about transmitting what has already been thought. The question of the canon is indeed crucial.

The sociologist Lewis Coser once jokingly characterized intellectuals as second-hand dealers in ideas.[4]Lewis A. Coser, Men of Ideas: A Sociologist’s View. New York: The Free Press, 1965. I cannot immediately find the page where he gives this characterisation. Theory teachers in art schools are often intellectuals dealing in fashionable expressions. That knowledge is very useful to those students aspiring to a career as art maker: they need the right buzz words when writing dossiers, selling their work, talking with critics. Off- and on-line talk are hyper-important in an art world; it’s crucial one uses the right words when networking.

5. (ON IRRITATING THEORY)

So, what to teach? Not only fashionable expressions, not only critical theory, but first and foremost irritating theory. I advocate criticality in theory; I defend irony over knowing better and the cynicism often accompanying it. Yet that criticality should not confirm established cliches of being critical, and the irony must not just be entertaining. The primary task is to irritate. Being friendly is not a virtue in the kind of theorizing I favour. Of course, this does not eliminate the possibility to teach unfriendly theoretical insights in a friendly way.

An example of irritating theory might be teaching a course on the concept of beauty in an era that spits out the word beautiful when it comes to art. Or perhaps teaching hard core Marxist class analysis in a subculture that indulges in identity politics and preaches intersectionality – yet that is conspicuously silent on the class background of the average spectator or on the harsh precarity further down the social ladder.

Theory particularly irritates, not least in artistic contexts celebrating individual expression, when it is radically a-humanist and brackets the evidence that one is an autonomous subject making self-consciously personal decisions, which are subsequently translated into intentional actions, life plans and other liberal virtues. Irritating theory questions the dominant ideas on agency and individuality, partly in the form of ideology critique (for they vastly legitimize neoliberalism), partly in a more principal mode when it comes to the notion of “the human” as such. Be it structuralist or post-structuralist, the decentring of the subject must remain at the centre of theory teaching.

“The human” is a moral-ideological notion. Its performative impacts are vast and also positive, witness the idea of human rights. However, “the human” – the human being, a human person, humanity – does not constitute a genuine scientific or theoretically sound object of knowledge. There exists no human sciences, except as a critique of the notion of “the human” through the research and theorizing of anonymous structures and systems on the one hand, their self-regulation and modes of self-organization on the other.

What is commonly called a human being is a collection of alternately loose and structural couplings of various potentialities, such as the one to move, to digest, to think, to speak, to affect and to be affected. These capacities operate according to complex self-regulations, thereby entertaining input-output relations to other self-regulating potentials. A so-called human being is a shifting state of relationality, a self-regulative plane of consistency made up of capacities. To say “I understand you” may be a moral obligation in some situations, yet it is theoretical nonsense.

For that matter: we meanwhile realize that our subjectivity is dependent on a hypercomplex system called the environment. The anthropocene is a reality becoming ever more real.

6. (ON AUTHENTICITY)

Teaching for social systems theory or psychoanalysis allows one to vastly irritate those students – and they are many – who believe in the possibility of an emotionally authentic communication. Yet it’s quite easy to see that there’s a fundamental split between what happens in the mind or the body on the one hand and communication processes on the other. Thoughts or emotions are private whereas communication is public; thoughts or emotions are inaccessible for any other whereas communication is per definition accessible.

One may communicate about thoughts or emotion – or blood cells, neurons etcetera – but they stay “inside” the one communicating. The communicative sender can therefore always feign emotions: the principal split between the private and the public, the individual and the social realms is the ultimate condition of possibility of what is commonly called personal freedom. To put it bluntly: no freedom without the possibility of lying.

Given this split, a person can never claim authenticity when communicating about emotions. Authentic communication is theoretically impossible; one can only believe that a communication is sincere, or that an emotion is directly and therefore truthfully expressed by another whose interiority is per definition a closed book. Authentic art is art faking authenticity – which may then be believed.

7. (ON /THE/ DANCE)

There are at least four terms involved when seeing a performance: a choreography, one or more dancers, the dancers’ actions, and the dance. These are the usual distinctions, to which I’ll stick here. It’s important to keep the four terms separated. The dancer is not the dance; the dance – and hence, the dance’s performativity – is that what is at once immanent to and emerges out of the interactions between the score, the dancers and the dancers’ actions. And yes, when speaking of a public dance performance one should add the viewer plus the relations between the viewers, resulting in a collective gaze.

During a performance, the dance is nowhere – and everywhere. An individual can learn dance movements and master dancing – but the dance exceeds the individual. The choreography, the dancer and the dancer’s actions make the dance possible to happen. Add to this the public’s gaze, music and lighting, and the point becomes even more clear: the dance is a living multiplicity immanent to and emerging out of a heterogeneous assemblage consisting of nameable elements, yet whose very nature escapes us. It’s here, now – it’s nowhere. It’s a virtual reality. It’s an imaginary object. It’s a phantom.

This is Part I of the essay. To read Part II, click here.

This article was originally published by E-tcetera on May 14, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rudi Laermans.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

Notes

| ↑1 | With the exception of the introduction and the preamble, this text restates my farewell lecture at P.A.R.T.S., delivered April 26, 2022. I’ve been teaching theory classes at P.A.R.T.S. from the school’s inception in 1995 until 2021. I wholeheartedly thank Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Theo Van Rompay and Charlotte Vandevyver for their immense trust: they never asked me to legitimate the content of my teaching. My biggest thanks go to the subsequent generations of students for their eagerness to think along, their respect for the autonomy of theory, their tolerance towards my painful elaborations and shortcut provocations in ‘globenglish’ and, particularly, the many ways in which they created a climate that invited me, even regularly pushed me to think aloud and voice personal thoughts. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Giorgio Agamben, Taste. London: Seagull Press, 2017, p. 63. |

| ↑3 | See, for example, Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford (Cal.): Stanford University Press, 1996. |

| ↑4 | Lewis A. Coser, Men of Ideas: A Sociologist’s View. New York: The Free Press, 1965. I cannot immediately find the page where he gives this characterisation. |