My mode of being, as a dramaturg, begins with looking and continues with language. Much of my work takes place in the rehearsal room, accompanying the process of devising and setting movement material.

In this setting, I see movement in front of me, usually on a stage or studio floor. Sometimes on a screen. In The Space. Once it is finished, I pause for a moment to let something settle and draw up lots of lines of my thought into a point where I can start talking about my response.

I respond, to the collaborators in the room, in spoken language, translating my feelings and impressions, images, sounds, and traces in my mind’s eye. I pick out things that stick. When I close my eyes, what leaps to mind? It could be one static picture. It could be a feeling permeating the whole thing, a kinaesthetic desire.

As I talk, I need to think about how to word these responses which are not necessarily initially framed in language. My speech is not complete; as I talk, I chop and change direction, I repeat myself, I use words I’m not sure I understand or anyone else. Then I try to be clearer and realize I am saying something different.

There is slippage between the signifiers of words and language structures and the feelings, thoughts, imaginings, and sensations that I am trying to communicate.

I don’t just talk; I gesture and I move. Sometimes, I get up from my floor sitting position, and I try to imitate movement qualities, illustrating my speech.

While I watch, I also write things down. This feels like a permanent activity, and it’s one that can be seen by the other collaborators. Even if they have no knowledge of what I am writing, or why, just the fact that I am doing it can feel judgmental–and I am aware of this as I write. On my part, it can be a screen for giving the impression that I have lots of important and insightful things to say, immediately.

I don’t always. There is silence too. I try to make silence possible, though it can feel uncomfortable. I try to lengthen pauses, to open up a pool into which collaborators can chuck a few pebbles to see what noise they might make, how far they might go.

I ask questions which hang there, feeling in need of being answered. Even if I say, “you may not know right now. It’s something you will need to decide. It’s up to you.” It doesn’t always feel “up to you.”

My dramaturgy is a language-based practice. But I asked myself the question: How could I do all of this in movement, with no language, no words articulated, none written down? What would I see and reflect? How might moving as a dramaturg be different to moving as a choreographer or a dancer?

And then for the outcome of my responses: What would collaborators see, how would they turn it over in their mind, and how would they respond to it–and how would I respond to that?

What right do I have, as some who is not professionally trained as a dancer or choreographer, who is not making this work, to enter The Space and fill it with my body’s movement?

Well, I tried it.

It turns out that dramaturgical movement response IS choreography. It creates in me the possibility of opening up my own understanding of what I am doing. It strips back the reality crystallized by language and turns it into the myth of polyvalent movement. When together, my collaborator and I can communicate as improvising performers, bouncing ideas back and forth more quickly than I could even think about words.

I let loose those inhibitions of moving my body and occupying The Space. I realize that when I talk, it’s a bit like a dance; it’s just that my fluency of language clothes the “dancing” in demure and formal attire. Actual dancing doesn’t have so much of that, for me. I don’t have the same fluidity or familiarity with my body’s movement languages as I do with words.

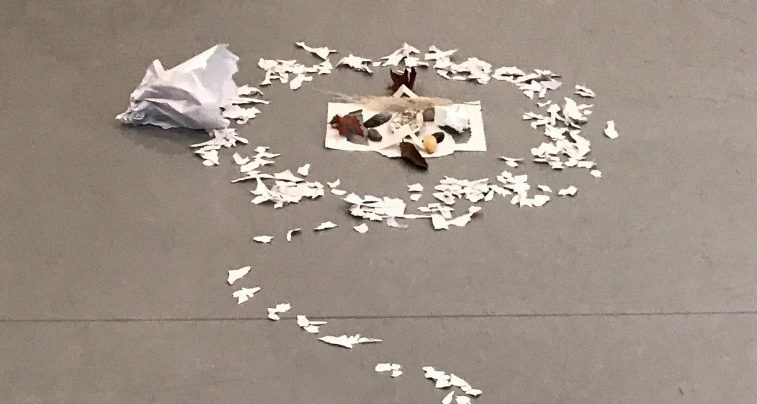

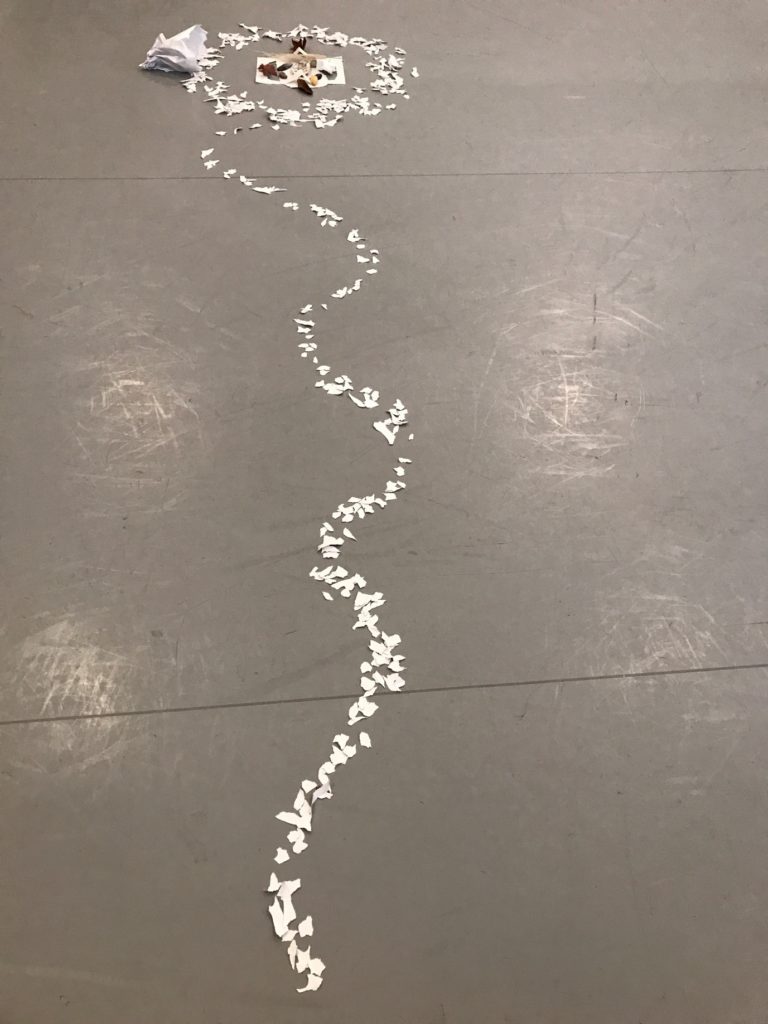

Photo Credit: Cecilia Macfarlane

Collectively, we make, dialogue, find out. That’s my role as a dramaturg, to help my collaborators find out things, move from one place to another. We generate a dramaturgy together, in the space improvising with movement, props, and music. We laugh and interact as ourselves but in a different plane.

I make choices.

I think in words in my head.

I let my body do some stuff that it wouldn’t habitually do.

I let my body loose on a free flow of associations.

I am playful, stupid, undecided.

I am stilted, unoriginal, hesitant.

I let chance take over, because it doesn’t matter.

It matters–it makes matter, by mattering. The matter of that matter is probably ultimately the same kind of matter that is created through spoken language, but I got to it through a different path.

Somehow at the end, I know something, though I can’t quite put it into words, and I am scared I’ll lose sight of that knowledge because it wasn’t worded.

While I move, small epiphanies explode around me.

There is something about how I can be in The Space and it’s fine. It doesn’t matter what it looks like from the outside, because my collaborator is within, even if they are observing. It doesn’t matter what the movement is.

Now, we stop, and breathe and laugh, and sit and sip. It’s time to ask questions in words.

I have noticed that the power dynamics in our relationship have shifted, or rather they shift; they are in the process of shifting throughout our movement and now. As a co-mover, I stepped away from the pen and paper; my eyes moved within my moving body, so I saw things from within. I entered into The Space, and it gave me a 360° understanding of the work.

Dramaturgs talk about subjectivity and objectivity. We rest somewhere in limbo between being a trusted outsider and holding on to an in-depth understanding. I transgressed some sort of barrier as I entered The Space as a co-mover because it felt like moving could only be a subjective response.

It makes me reflect on what I already know: language might help me sound objective, but everything I say, do, and think as a dramaturg is subjective. That doesn’t mean it’s less good. By entering the space of the maker, I liberated myself from the restrictions of a binary understanding of dramaturg versus maker. It enabled me to inhabit a multiplicitous world which embraces subjective understanding as a valid way of knowing.

In the best tradition of dramaturgical practice, I end with questions.

How has this experience changed the way I understand my own practice of dramaturgy? Could it be a creative, generative one?

What would happen if the person I am working with is the watcher and I am the mover, instead of us both moving together?

What difference does my moving response make to the next steps of the other person? Because it’s their next steps which are what it’s all about.

A version of this piece was first published on www.mirandalaurence.co.uk. It describes an experiment made possible by a residency at Pavilion Dance South West in November 2017, together with Cecilia Macfarlane.

Miranda Laurence is a freelance dance dramaturg based in the UK. She has been awarded a grant from Arts Council England for professional development as a dance dramaturg in 2017–18. She works with dance artists across the UK and also internationally (most recently with Finnish choreographer Johanna Nuutinen, enabled by an award from South East Dance). Miranda has also directed the Dance & Academia project based in Oxford since 2008, convening a number of seminars and conferences engaging movement practitioners and academics in many different disciplines. Alongside her freelance practice, Miranda is employed as Arts Development Officer at Reading University, where she is devising an arts strategy for the university.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Miranda Laurence.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.