In July of 2020, Disability Arts Online (DAO) announced their three Associate Artists—Ashok Mistry, gobscure, and Letty McHugh. For a period of two years, these artists will work alone and collaborate with each other and the DAO staff to explore their various art forms. DAO is committed to supporting marginalized communities, which is shown #WeShallNotBeRemoved participation. Trish Wheatley, CEO, explains the hashtag as “a vital and urgent coming together of Deaf, disabled and neurodivergent artists in the UK. Disability Arts has its roots in campaigning for disabled peoples’ rights. Politicians, funders and arts organisations are now listening to this strong collective as we work to ensure an #InclusiveRecovery.” In relation to the Associate Artists, she says they

“are key to Disability Arts Online supporting this because they sit at the heart of our organisation as paid experts, creating art, having a voice, influencing policy and reflecting on the experiences of disabled creatives.”

After giving the Associate Artists some time to reflect on their new positions, Madison Parrotta talked with each of them about #WeShallNotBeRemoved, their time with DAO, and their mediums.

Ashok Mistry

How does “truth” play a role in your work?

I was brought up in a quite religious household, and those beliefs were presented as truths. And there was a point at which I started to question a lot of that and in general as well in society. The way school happened, the way my family interacted with the people around them, the community around them, and so on. There were certain things that were held up as truths. And what I do in a lot of my work is try and understand where certain truths and things come from and where they’re formed and how I actually understand them. And whether they are actually true or not. We take so much for granted, and it gets worse and worse with technology and stuff. Before it was more word of mouth. And people would act and react based on what they were told. So there were beliefs in all sorts of settings like in things like superstitions. They’re completely irrational, but people see them as a kind of truth. And there’s a fear attached to that truth. You don’t want to tempt fate, just in case. So people weren’t smashing mirrors, people won’t do this, people won’t do that, people won’t let the cat cross their path. They don’t like uncertainty. People love certainty. And I think that’s where truth comes from.

Ashok Mistry | Photo Credits Ashok Mistry.

You’re the first person I’m telling this to. I have always lived in uncertainty because there was always a difference between how I saw the world and how the people around me saw that world as well. And you probably understand this yourself as well. You’re told that you’re a certain way, or you’re told that certain people are that way. And you’re expected to believe that. What I’m doing by exploring truths is understanding that cognitive difference between myself and the people around me.

Can you talk about how you use questions to guide your art-making process? What might those questions be?

The questions are aimed at these truths so that the questions are, for instance, why is something a certain way? Why can’t I fit into a certain situation? Why can’t people see this? Why can’t people empathize? Why do people allow this to happen? Why do people turn the blind eye? Those are the sort of questions that I’m essentially exploring in a lot of the work. There are also more abstract strands that don’t explore more concrete themes. For instance, there was a piece called Under The Skin. And that was kind of looking at this whole idea of organic and inorganic through form and the solidity of things. The questions were more on a different level, they were on a maybe a deeper level, in the sense that what are the differences between these two things like the concrete, the geometric and the organic, what are the difference between these two things. How they are related and how they diverged in some way and how do we represent these concepts through things like color and so on. I think what I was trying to do there was really explore this whole idea of synthesis and something being synthetic as opposed to something being natural. And this whole kind of vocabulary around nature and how real that is, how true that actually is because there were a lot of things around me at that point, there was this whole move towards the organic and towards wholesomeness, and so on and so forth. I was trying to react to that and trying to kind of interrogate that vocabulary and look at whether the word natural actually does mean anything really, whether natural means natural or not. I’m trying to explore particular tangible, everyday things, but in a very abstract format.

gobscure

Tell me about your name, gobscure.

Basically I was doing a thing in Mid Wales quite a while back. And so there’s just a little notebook. It’s a square. It’s just a few inches. It’s quite, quite small. In the background sort of gray, boring gray writing, and what I did, and in the end, I came I think it’s about 54 different words. It’s a little notebook with this official purchase in the background and so all the words are made up of real words, and they’re literally existing with prison and song or gob, and obscure, or scorch and orchard or slang language and the 54 of them in total. It was literally just a case of actual real words that exist and I’ve just kind of crashed them together. And like prisong, well, just turning prison into song. Some of them are positive. Some of them are weird. Some of them are strange, some of them are not aggressive but challenging, like madvert, so mad in terms of Manhattan and advert and it’s a wall of words that are brand new words. Gobscure is poetic, but they are literal, actual real words just kind of put together to make a new meaning. So that is quite literally where gobscure came from. And also talking with a friend who was a director. Unfortunately, she had a brain aneurysm and died. But before that, we were working together as this kind of thing of, well, what’s the word or the name? I don’t like branding and things, but the umbrella term that might be useful to just put these things under. In the end it’s gobby but obscure, not deliberately, it’s just being excluded and ignored. So that’s why and there is an actual wall of words now and they are that notebook size and then all the pages torn out, there’s 54 of them. And we’ve sort of put them up around places. Sometimes I make extra ones. So like prisong, and it was it was exhibited in a library two, three years ago. I put extra pages in it, made more copies of prisong and hid them in books for people to take away so the people got some sort of free art.

Can you give some examples of the “playful and poetic creative resistances” that you offer? How does your art work to resist?

Well, I mean, first of all, there’s so many people out there that I also admire, and that’s what they have done hundreds of years ago or are doing right now or 40 years ago, or wherever in the world. I suppose one of the things was tha people I’ve met have inspired me or things I’ve seen. One of the artists I admire is Doris Saucedo, never met her, but she’s Colombian and the things that she does with flowers or chairs to remember collective mourning and collective green is amazing. There are amazing people around the world doing these things. And there’s, again, there’s a band from Northern Ireland called Stiff Little Fingers. They were part of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. One of my favorite albums is their album Hanxs and I have written a whole play, which is about 1981. And that album is an important part of it. The thing was that they were a young band, and it’s only been recognized in the last couple of years that actually, those bands in Northern Ireland contributed to the peace process in Northern Ireland. So you had these bands, young people, sort of bringing together people from either side of that divide and realizing that they’ve both been lied to. There are these wonderful people in whatever art form, for whatever reason, doing these sorts of things. So it’s kind of like a continuum of these sorts of things. I find it interesting or exciting. They’ve inspired us.

Hyena in Petticoats: Part of a body of work celebrating Mary Wollstonecraft who was mad, bad, rad, bi, mutha, internationalist, feminist-b4-the-word, pamphleteer & more. | Photo Credits Shân Edwards.

And another person was called Sergei paraJanov, who was a filmmaker into the Soviet system. And this spring, it took 17 years — one of our projects is called roads carved in rain. Some of it is installation. Some of it is an album of sound. Some of it is prose poems. Some of it is sculpture. Some of it is a performance. There’s all these different bits. It happened in different ways. It took 17 years to make possible, and it finally happened this spring. It was in honor of this person who, well, he was Armenian and Georgian heritage, but he was under the old Soviet Union system. He was also bisexual, he also had huge mental health issues. And his art was incredibly beautiful and playful and childlike, the most amazing images that he made, and they were unlike anything else, and which is also what got him into trouble. There’s photos of them jumping around and things. He’s just this big kid, and when I saw him and his art and things like here is someone under the most incredibly repressive regime, and yet he’s still full of life and still refusing to be beaten by it. I made this whole body of work kind of around that or exploring that is a performance or theater, if you like. We were handing out dissident patches around the Northeast, in where I live, Newcastle gates here, also in Yorkshire in Leeds, and people were very happy to wear dissident badges for some reason and were writing in liquid chalk markers at restaurants, just drawing across glass. And again, it’s not “oh, there’s the professional. There’s the workshop or the participation or the education thing.” Sometimes it’s all mixed up. And since working with people and sort of giving them back instructions can steal some time. They were phoning up their mates at work to sort of tell them jokes and things to relieve and or some of them are going out into the pedestrian crossings and dancing. And so there’s a kind of giving people permission to play and ask questions and perhaps be silly. Here are people that I like and admire that have used creative resistance, that make art and challenge the headings or ask questions. So that was something that I was doing this spring.

I was being driven back from Leeds, and it was like literally two days before lockdown. Here, there was a lockdown for three months. I’m in a particular high risk category. So because of various disabilities, I’m not going anywhere or anything like that. All these things like red tape is bad, red tape saves lives. It’s a lot of just playing and I had loads of red tape and was handing it out and inviting people to leave messages on it. Just being playful and having fun and some of it is visual. Some of sound is more theater or clown. Some of it is just people exploring and playing. It’s a mixture of things. And I think we need it more than ever right now.

And the other element is that whoever you are, you can have incredibly little resource, whether disability and lack of, whether it’s money, whether it’s homelessness (I have experienced homelessness). But there are still things that you can do that are creative. And again, you don’t have to say, “oh, I’m a poet, I’m a dancer. I’m a singer.” There are still these creative things that you can do. It’s really just that widening it out. It’s not “oh, is this a painting, is it art, is it theater, is it…” Explore and play, reshape it or redefine it, rather than worry too much about the box.

Letty McHugh

I’ve looked at some of your blog posts and noticed a theme of emergence. You talk about what it means to emerge as an artist. Can you expand on that? Do you feel as though you’ve emerged now?

I’ve been talking about emergence a lot because in 2018 I received a bursary for emerging artists, which is called the emergence bursary. That’s what sort of started making made me reflect on what it means. The final event for the first three was due to be happening at the Tate. Just before it was over, the first week of COVID locked down in the UK. So we’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to emerge as artists and a sort of power around being emerging artists because we were all very new, but we knew we were having this opportunity to be in the Tate exchange, whereas a lot of other emerging artists weren’t. That’s why I was really thinking about it. Would I consider myself to be emerged now? Not really. I still feel like I’m in that very much. Maybe further out I think I would define myself as emerged.

Once you finish with the associate artist program, will you feel emerged then?

March 2022 is when the program would have ended. Who knows what might have happened? I know the idea of the associateship is that we’re are all at very different stages of our careers, it’s a pivotal stage. So the support from DAO might help us get to that next stage. So, maybe. I don’t know if it’s the same in the stage, but here there’s three distinct stages when you’re applying for opportunities. It’s emerging artists, mid-career artists and then established artists. It’s generally on funding opportunities. I think maybe by the time I get to the end of the associateship, I won’t be in that emergent artists category anymore. I’ll feel like the next thing.

Letty McHugh | Photo Credits Rob McHugh.

Your work explores personal experiences as universal. How can something so intimate be considered universal?

We all experience emotions. We all have stuff in our life like joy, pain, suffering, happiness, love. Those are universal things. But I think the way the personalized universal comes in in my experience, if you talk about those things, just generally, people find generalities or less relatable than, like specific details. So, to give an example, in the companion book that I wrote, I tell a story that I thought was really specific to me about I found the stone on the beach, and I thought it was maybe like a prehistoric arrowhead, but I didn’t want to do a Google investigation, find out that it wasn’t. And I compare that to my own feelings of maybe a little bit of imposter syndrome. I don’t want to find out I’m just a stone and not an arrowhead. I felt like this was a really personal story to me. I got an email after I checked the book online a little bit from a lady who said, she had had almost the exact same experience; she had also found that this stone on the beach, and she thought it’s kind of arrow-shaped and it became her personal talisman. When you share the specific details of your own experience, people find it easier to sort of fill in the specific details of their experience. That’s where that universality comes in. It’s like if you talk about your family, people won’t necessarily relate to the exact details of your family. But in sharing those details, it makes them think of the specific pieces of their own family life.

All of you work in different mediums. How does this contribute to your artistic messages?

Ashok Mistry: When I finished university, I trained in painting and printmaking, but mainly painting. My major was painting. And I thought I knew everything about painting. I thought I was the thing when it came to painting. I really thought a lot of myself. But I couldn’t paint because there was nothing for me to paint. Plus, I didn’t like the way I was taught. And I was kind of trying to get some of what I had been taught out of my head. Because while I was at uni, it was almost as if I was kind of at loggerheads with the tutors. And I was trying to take it out of myself.

So I got involved in all sorts of different media, including theater as well a bit later in life. But what I didn’t realize was that learning all these other media was actually teaching me how to paint in a weird way. It was actually teaching me more and that’s why I’ve kind of gone back to painting recently. So I paint. I do other things, I write and I’m trying to make theater as well — trying being the operative. But because my approach is that, in the same way as a scientist uses different processes, to understand and to find evidence of kind of particular phenomena or kind of physical evidence in some way, what we as artists do is we use different media, but to find emotional evidence, and to find emotional kind of find something on an emotional level but can’t otherwise be seen in the everyday. So for me, it’s all about fitness for purpose.

The media doesn’t come first, the idea comes first because what I tend to do is to write a poem first. So all these things are rushing around in my head. And what I’ll do is I will usually clarify that in the form of a poem of some sort. And from that poem, I actually tried to work out what the best thing is to use. So whether it’s video or some kind of movement or paint or something else, it can be something ephemeral in some way, and that’s kind of my process. That’s my way of working. And from the poem, I veer off into different situations.

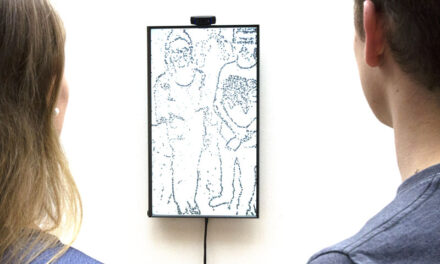

For me, theatre is really important because it was at that point where I went through a really rough patch around 2013. It was almost like I was having this out of body experience. At that point I knew that I had certain things about me that other people didn’t like. And I’ve been trying to battle and hide those things, like really messy handwriting, never putting sentences and things in the right order, missing things, bad memory, being late for meetings or never getting to certain meetings, and just generally really sketchy. But at that point, it all solidified almost. And it was almost like I’m seeing all of those traits all at once. And it was scary. But what I realized was, there was a difference, there was a cognitive difference between me and the world around me and I wanted to understand what that was. So through theater, I was able to kind of understand that and the piece that I made was — some people would call it theatre — but it was a data-driven piece of theatre. So the whole piece was called Methods for Misunderstanding the Nature of Things. Basically I used technology to connect up and drive data to performers. So all of their instructions — what they were going to do on the stage — happened in real-time. I used Twitter data, and I connected it up to a drummer and his drums. And so basically he was getting instructions in real-time as to what to play. And the dancer had to dance and so on. For me, it was like one of those pieces that was always inside me, but it was kind of me having to come out of myself to actually understand myself.

It frightens the hell out of a lot of people from fear. It frightened the hell out of a lot of musicians as well. I had one musician come up to me saying that, “Oh, it’s an absolute insult to musicians, because we don’t take instructions and that.” But on the flip side, that drummer that I worked with, he said to me that at first, it was really difficult to listen to that kind of instruction, and follow that instruction all the time. And even the instruction was very random in the sense that there were notes that he would never put together. But what he found was, in the end, it was very liberating because what he was doing was he was finding note patterns that were beyond any of the conventions that he’d worked with. And it actually enabled him in his own practice to open up more and think a different way and find patterns in things that otherwise wouldn’t been there.

Photo Credits Ashok Mistry.

gobscure: Well, two things. We just want to use whatever to help convey a message or explore a place for us. I don’t like being nailed down and probably the first thing that I always work with is our work. It mostly comes from even if there’s only two or three words now, and that is loads of visual sound, but so it probably just starts off with a text type based thing. But I guess the thing is, one, there are different ways of getting it out. It’s literally just what I want to say, and what’s the most interesting and useful way of doing it? And more and more playful? I think it’s a really wonderful positive. But the other thing is that unfortunately, when trying to talk to people in terms of the gatekeepers of the venue, and then even within performance, they want to know, is it theatre? Is it live? Or is it cabaret? And so all of those weird divisions and then well, it’s like, well, it can be an installation and a gallery and we can play around and actually have a performance and do something else, does it really matter? I don’t think it matters and I love it, but unfortunately people who mostly make the decisions tend to not like that, and tend not like that messiness. It does create difficulties that way. It sort of keeps you down or keeps you outside or you know, locked out of the places that you would love to do it in most perhaps, but it does allow freedom in other ways.

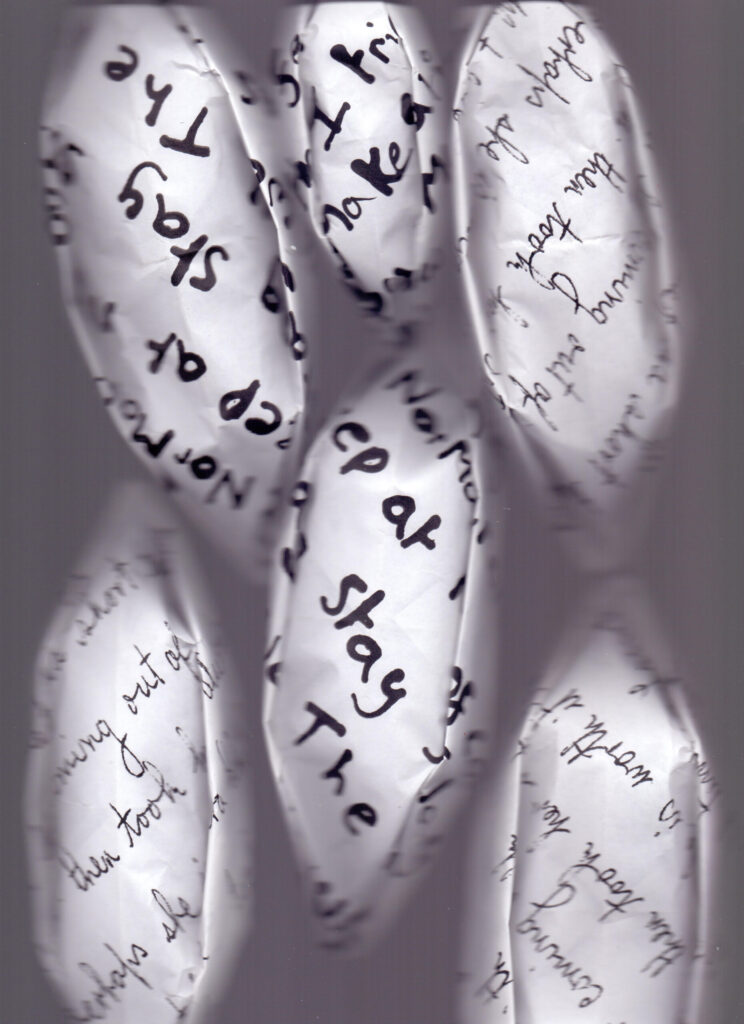

Letty McHugh: The important part of my work has always been stories. It’s about telling stories. I ingested a lot of art theory as a student. All this stuff about art should be a tool for communication. I think when I’m approaching how to make a specific project, the question is what is the most effective way that I can tell this story. But then there’s also the relationship with the skills that I have, which is, I grew up in a family where everybody sews so I have textile skills. So that’s just kind of a natural thing for me. I like working in paper. It’s cheap and it’s available. I know how to use it. I try to think about, you know, the name that comes with specific media, but it is also about my resources and my skill set. And that kind of relationship between the really ambitious ideas that I want to make and like, how can I make that happen with what I have and what I can afford?

Which of your previous pieces do you feel encapsulates the times we’re currently living in?

AM: There are some pieces but they’re all written pieces. I’ve written particular poems, but I haven’t published them. So there are things that I’ve made, things that I’ve written that connect directly to the times that we live in, but they’re not in the public realm yet. There was a performance I made in Taiwan called Under the Skin. And it’s a performance I made with someone called Hsin-Yu Chang. But anyway, that piece was all about the tension between an individual and a group. And that whole idea of invisible connectivity between the two and an invisible control. So you’ve got the broader society, and societal rules and then you’ve got this individual that’s trying to exist amongst that.

g: One piece is a short film called Mazer that I did just make, and it introduces a sense of now. So, one is there’s a whole different strand to them. The other thing is that this is also only part of a bigger thing. My next full-length play I want to work on is “The Last Day Joey.” The idea was to actually take this whole concept, that film because it is about my friend Marty, and actually turn that into a full-length play. It is kind of an ongoing project body but in terms of that piece, Mazer, it is about now, but it’s also this thing that I’m interested in of inverted commas, rewriting the future. But to say that there’s a certain American top down political narrative, just as there is here in media and those sorts of interests, and then there is actually everyone else we’re speaking about. When I say rewriting the future, we’re told a certain set of values, a certain set of perhaps inverted commas, truths. And actually, what’s the other stuff that we can say around it? One is this thing of rewriting the future in Mazers is about that. It’s not just about now as in 2020. This event is happening, or I’m writing about 1981. And that happened or something. It’s the timeline of history, this is happening now. But these are the things that led up to it. And these are the things that could change down the line.

Marty was my best friend and she was, in inverted commas, the littlest old lady. She said, “I hate thinking of myself as a little old. But I have to remember at the end of the day I am.” She was more or less chair bound on oxygen. She had TB during World War Two in an air raid shelter. She had traveled to San Francisco, Venice, which were her two favorite places in the world alongside Walker, which is part of Newcastle. She did incredible, amazing things. And she was this amazing person and she was online and connected. But she was saying, “Well, in those cases, I am frightened, I have to remember my limits.” The whole social care system, especially under cuts was absolute crap here. Appalling things go on. She was the most imaginative, bright and wild minded incredible person. She spoke her mind and the thing was when’s the last time we saw a much older person on stage? Carol Churchill does, and I love her characters as well. It’s fair enough to do it, but it becomes old person’s issues, we’re talking about dementia, and it’s and please, let’s talk about that, that’s fine. But Marty was the brightest, the smartest, the what have you. There are so many things to celebrate so it’s a kind of an essence of her and actually a one person, online virtual creative resistance remaking all kinds of things. So, there are the specifics of her life and we can learn from that WWII, but she was the most generous and intentional person. She also believed in growing things and plants and things which is why all the plants- my backyard in the film of Mazer. She taught me how to grow stuff. I’m not really someone that plants and grows things. And she gave me a couple of roses in the final months of her life and they’re in pots out there. Amazing practical lessons and impractical and jokes and wickedness and amazing laughter and these kinds of things. Unfortunately, she had a slip, not even a fall, she was on the edge of her bed, and she slipped and she was taken to hospital. There were no bones broken. Obviously, she was incredibly tiny and petite and skinny, so it hurt a lot. Psychologically it was a kind of, “Oh, I’m more frail now than I realize” in the sense that she’d kind of have to take more care. But and again unfortunately the hospital and there was the inquest, there’s all kinds of things that happened. I had to attend this. And they did admit that basically they got every aspect of her care wrong and it was this horrible kind of, she’s a little old lady.

She went over three weeks, they gave her pain relief. It was actually contraindicated. They gave her oxygen, the wrong flow, in terms of the volume of oxygen, the temperature, humidity, so she was choking. Collectively they got everything wrong. And then this is horrible also, we saw that 15 months on the inquest, they admitted in terms of oxygen, they got every support wrong. At home she was under the care of the ventilation team who did work with it and who did know and had a mask made that did fit her face because it was very small, but not quite child-sized. The care at home was decent, in hospital it was appalling. But in terms of in the inquest, and this was in February, this year, the way that the hospitals work is different trusts. This was just the patch around where I live, they realized that they had got oxygen completely wrong. They actually changed, which is horrible, but even in her death, she was kind of almost like saving other people’s lives. They made three major policy changes. They also said they were going to then send them to the whole of the NHS England and nationally to cardiothoracic because that’s what she came under. They were sending it, then COVID hits. And he then had the prime minister who I can’t support for all sorts of reasons. He’s an idiot, I’m sorry. He made this weird sort of fake competition of inventing new C Pap, and continuous press for airway machines, as opposed to non-invasive ventilation, which was the one that she was. Even if in death, if people actually listened to her inquest notes, rather than to the Prime Minister, they would have had a very different policy and a very different outcome. So there’s a whole thing there but it’s actually celebrated.

And then the other part is this whole thing. There is this Viking legend, you know, sort of Norse legend, so the Norse poems, and the final one is “Völuspá” and the thing was 1000 years ago. Sea levels were rising. Now, if that was climate change, because climate emergency and obviously, now it’s human driven, that was volcanic activity. A thousand years ago, people were thinking very differently in that they realized that climate change was happening. To them it was kind of the end of the world so it had these legends and stories. But ”Völuspá” is about the wise old woman. You have all these gods fighting and killing one another off. But actually, the end of the world wasn’t–that was only the death of the gods, but it was this wise old woman who basically looked after humans, and then kind of led them to safety in regrain to the earth. There’s this legend that’s ancient, but some of the parallels are about now. Climate change or climate crisis, and then this whole thing of, it’s who do we listen to? If we listened to the people with the lived experiences of–listen to disabled people or people from where I live, sort of Newcastle, rather than just London. I’m guessing maybe if we listen to people from New Jersey more rather than just certain other places, but apps or certain demographics and so it’s just about who do we listen to? Who has the knowledge, the experience. And I think disabled people are problem solvers, we’ve probably got less energy, less voice, less time. We sit down, work out the solution, and then if we were listened to things would be very different and probably best or more equal or something like that. There’s the thing about now, but also all the future and also bits of the past too.

LM: A lot of my work I’ve been looking at, I started out looking at this idea. That’s how I first started looking at emotional resilience and stuff, but this idea of making survival equipment for emotional emergencies. I guess that kind of feels like relevant at the minute where there’s all these traumatic things happening, and we’re all focusing so much on how do we stay safe, that we may be neglecting our own and each other’s emotional wellbeing a bit. And I also think my project, Sea Worthy Vessel, was a really good project to have just been working on when all this started. Because the journey that I went on with that project was sort of understanding, I think I started out where I thought that I was looking at all these questions around value, and I think it so the question was, if you could apply seaworthiness to people, like who would be seaworthy? I think at the start, I sort of felt like I wouldn’t be sea worthy. And then going through the process of working on the project. Like the research that I did, and going to Norway, and I’ve learned all these stories about ships that had been sunk, and then refloated and like gone on all these crazy adventures. And I sort of learned that in ships this idea that I’ve had of seaworthiness wasn’t as straightforward as I had originally thought it was. It made me feel like that as humans, we have this buoyancy that is similar where we can at one point be damaged, but then we can recover. And I feel like I felt like at the start of the COVID crisis, like I’m really glad that I’ve just been all that time working on this because it makes me feel like the terrible things are happening now-we can recover from them.

Seaworthy Vessel | Photo Credits Letty McHugh.

Do you feel your work relates to #WeShallNotBeRemoved? If so, how?

AM: I think it does. I don’t like to make work that’s specifically about disability or race equality in terms of a struggle. What I’d rather do is look back at perspectives and look at how people perceive each other. So, there are aspects that connect to that to that movement in that hashtag and that campaign, but one of the things I really dislike is a kind of like the exoticization of disability and of race for that matter as well. Because the problem is that for me it suggests that there’s a resistance to change. But there’s also a very surface understanding when you exoticize something, it’s almost like you don’t want to change, you don’t want anything else to change, you don’t want any structures to change, but all you want to do is to kind of hold that issue, almost like a cat and pet it for a little while and then just let it go. You know, there’s no real kind of like interest in it. It’s a curiosity.

g: In terms of We Shall Not Be Removed, again, it’s kind of a very new thing. I think the third meeting is being held this week, and it might even be tomorrow or it happened today or I don’t know exactly. It is very, very new. It’s like a lot of different individuals and organizations coming together. And obviously, people who are disabled individuals in the arts and organizations or disability-led. The Arts Council of England and obviously there is a separate one for Wales for Scotland and Northern Ireland, but it was strange timing, because mainstream organizations ignored disabled people forever. It’s probably something fairly familiar. You may have heard this before. But the whole thing of the mainstream organizations or big ones sort of saying, “oh, yes, we’ll do that” and then not doing it. And every three years the Arts Council would give them more money and say, this time you have to do it and they never did it. So the Arts Council did actually in their plan, which was launched probably about a week or two before COVID was a kind of, “Actually you have to do something about this. We’re going to put disabled people and poor people, and also people of color to kind of get to the front as it were, and you have to work on this.” That was a sort of the grand plan, then COVID hits and then all of a sudden arts organizations are fighting for existence and survival and all these sorts of things. And obviously, you have some wonderful, amazing organizations and then you have some who are quite horrible in their attitudes and people everywhere in between. It was really, this statement has been made and this commitment, but everything’s kind of falling apart. We are being hardest hit and then what is the research for larger numbers of disabled people? They, for example, are going to the theater and obviously, that’s only one form of art, but they won’t go to the theater until a vaccine is found. What are the bigger exclusions for us as communities in this group? It was that exactly the kind of thing of where if we’re being downgraded again, or raised again, if it’s not safe, if we’re not understood or heard, so it was about that kind of collective voice and collective support. It’s interesting, it’s great that lots of different people are kind of coming together under it. And obviously, DAO is involved in that. So I am feeding ideas and information to where it goes with it. I think it’s very, very early on in terms of time, so I don’t know what to call it or what will happen.

LM: I haven’t been massively involved in the “We shall not be removed” campaign. I did a bit of reading for it. And I’m not making my work specifically in response to it. Their overall theme is this idea that when the art world restarts, there should be space for disabled artists. That’s where I see the relation to my own work is that I think a lot of what my work is about is taking up space and exploring ways, I guess it’s saying my experiences as a disabled woman in the north of England, are valid and deserve to take up as much space as a posh man who went to Oxford. And I think that’s sort of the same spirit that is behind We Shall Not Be Removed is the idea that we are validated and we deserve to be here. Our stories are important, and we should get to take up space.

Do you feel like this is the right time in your career for you to be an Associate Artist with DAO? Why?

AM: I think so. I’ve had an association with DAO for a few years now. It’s been quite a nurturing relationship in the sense that they’ve allowed me to kind of see parts of the sector and kind of hold myself up to the light as well, in a way. A lot of the thinking that I’m doing is starting to crystallize now, in terms of my views around arts and disability. And more broadly, kind of my thoughts, my views around the sector as a whole. They’ve kind of given me like this space to really deep dive into some of these issues and some of these things, and really grapple with them in a meaningful way.

It feels right now, to be in this position, and especially with the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis, a very unfortunate time. But it’s enabled a stilling of the waters that were always too choppy to navigate across the art sector. I’d say internationally even. And what it’s allowed people to do is to look back. And when they can look back, they can find little people like us — these little associates — and they can see us suddenly, where they wouldn’t have seen us otherwise.

And I think it’s, you know, in that sense, it’s perfectly just, it’s really unfortunate. It’s just such a tragic time for a lot of people and such a dangerous time as well, especially for people with disabilities. But there is the, I wouldn’t say silver lining, but there is time right now to be seen, and that’s really important.

The best thing about them is they’re open. For instance, they will tackle subjects like race equality in the context of disability and beyond, or intersectionalities, whereas other organizations tend not to, or they do it in a very knee-jerk kind of way where it’s completely meaningless. Whereas with DAO, because it’s based around literature, there’s a chance for a conversation, an in-depth conversation. Whereas I’ve been on a lot of programs here, where, they’re looking for what they refer to us as BAME practice, and you’ll be kind of rushed in and out of this process. You don’t actually have anything to show for it. And you don’t really have any real meaningful connection or interaction with either that organization or with the sector as a whole. Whereas this way, it’s almost like I’ve got a mouthpiece to actually have broader conversations.

g: The answer’s yes. Absolutely. Gobscure, I’ve been obscure forever. I’ve done things forever. I’ve had a huge mental health difference my whole life. So that was my first disability. And then osteoarthritis, 10 years, and so on, so there’s–as a person, things are getting harder. Since the banking collapse in 2008, we’ve had 10 years of austerity in this country, and the region I’m based in the northeast, by far is the worst hit economically in terms of COVID. There’s going to be more cuts at some point soon. I’m sure we’re going to be the worst hit again. The whole Brexit thing, I’m not a fan, but in terms of the economic models, we’re going to lose more money and our region is going to be the second. So there is a whole bunch of things like that. Over here we have what was called PIP, personal independence payments. The state benefits for certain disabilities and things to sort of give you money to help with that. I’ve just had that cut into those things. And then unfortunately, again, in terms of COVID, the disabled community and of course, that’s also about being poor, black people, people of color, even worse hit, but the disabled are the vast majority of people dying under COVID and likely to go down the line as well unfortunately. The government policy, they literally split Britain up into either you’re in the herd which is a kind of fingers crossed, you’ll probably survive, although maybe you won’t and also if you do, maybe you then become disabled by it but the other lot, i.e. me, and then they even change the language so they didn’t even bother using disabled. We are vulnerable, we have underlying health conditions it’s a kind of bad us rather than okay, let’s look after everyone in the country, let’s support everyone and the people who need more, we give them more support. It was eugenics. As far as I’m concerned, it was a policy of that. And this is horrible, but in light of soft or nice. That’s eugenics, you know, polite, not the brutal sort, but also tidied away and hidden away. And then you use the word vulnerable, which, oh, poor you, but it was going to happen. It’s even disappeared from the narrative, the public narrative, the story, the medium. In terms of disability, money, poverty, worst cuts coming under COVID. It’s going to cause huge problems actually to have support, profile, help, advice those things is amazing. So, you know, I’m very, very happy to be a part of DAO.

ships-ov-fool (online) performance originally commissioned in 2020 for GIFT: Gateshead International Festival of Theatre | Photo Credits Liz Rose Ridley.

LM: To kind of go back to the thing I said about the other two artists, they have had longer careers than me. They’re more established than I am. But I think it’s going back to that thing of doubt -choosing artists who with a bit of support can get to the next stage in their career. And I think for me, I feel like I’ve been working to try and build up momentum and I’ve done a lot of that, that’s gotten me to where I am now. But it will be difficult for me to get to the next step on without that support or backing of someone like DAO. And they know so much more about like the industry than I do and like the sort of connections to be making so that for me it feels like they’ve opened the door for me. And, yeah, I think it would have been very difficult for me to get a door open without the support.

What do you hope to gain from being an Associate Artist?

AM: The real goal is change. I’ve been in the sector now for 20 years, and I’ve spoken to people who’ve been in the sector for 30 years plus. The real sad thing is the change is minute. Over those decades, the change is really, really small. And something has to give, we need to do something other than what we’ve been trying, there needs to be a different approach. And I think the really key thing for me is I don’t want other artists suffering the same way that I have. I don’t want them to go through those horrible experiences, the ones that kind of really break you down. If I can even contribute to something like that. I don’t think I’m going to really have a major impact or anything, if I can kind of like even just offer something towards that. It’s a bit like adding a little bit of butter into something that will melt away and become part of that solution, but that would be enough. Some sort of change has to come from this.

LM: I’m hoping that it will be a process that helps me stabilize my career. Things have been a little bit like stop-start for me for health reasons. I’m hoping that it will help me raise my profile, make some more contacts and get to that stage. There’s a bit of sustainability baked into what I’m doing in terms of the work and it was really unexpected to me when I got asked to be an associate artist. I didn’t see coming so I didn’t have like a vision of it before the opportunity started. I’m sort of in the process now trying to envision what two years, a year and a half from now will look like.

Anything else that you’re wanting to say to the audience of The Theatre Times?

AM: I think the only thing I’d probably add is kind of trying to understand a little bit more about where I came from. My parents are originally of Indian origin. They lived in the state of Gujarat. My ancestors did, my grandparents. Then what happened was because it was part of the British Empire for a while, I think it was after independence. Both my dad’s side and my mom’s side — they didn’t really know each other at that time — but they both moved to East Africa. They followed the Empire. And then that’s where they met and that’s where they got married. And then my dad — as things were kind of starting to kind of collapse there, the Empire was collapsing — he was told to leave basically because he had a British passport, then he had to move to Britain. And that’s kind of where I come in, I was born here. So I had this really weird relationship with this country in the sense that my ancestors helped build this place. And we came here for opportunity. My dad came here for opportunity, and yet, I still feel a sense of resentment towards me. Even in the art sector, there’s a sense of resentment towards me, or there’s a sense that people want to control which spaces I can and can’t speak in or take part in. And I think that’s quite important to understand. Because when I was a kid, I was trying to understand my place, and why I was here kind of thing. Why the hell am I brown and all the other people not brown? When I went into school, I was actually in the majority. I was like the cultural majority in school because what happened was after the whole Idi Amin thing, a lot of the people that that were expelled from East Africa came to Britain in the year that I was born so by the time I was six or seven, most of the people around me locally were brown. We only had a few neighbors that weren’t. But there was still this really kind of like unsettling feeling of why are we here? Why do we always talk in this other language and why – it was trying to kind of make sense of what was going on? And then as I went through school, I went from this majority into a minority as I entered mainstream society. It’s kind of like it’s a weird gradual process of going from a majority space into a minority space and becoming part of a minority. A lot of the things I spoke about earlier kind of come from that sense of dislocation.

LM: Just that DAO has been really important to my career and I’m really grateful for their support.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Madison Parrotta.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.