Politically motivated flash mobs and performances react to current questions of society with popular and contemporary forms of dance. For example, is it possible to give answers to oppression with the body? The theatre and dance scholar Susanne Foellmer explains how such a kind of protest can have a public impact.

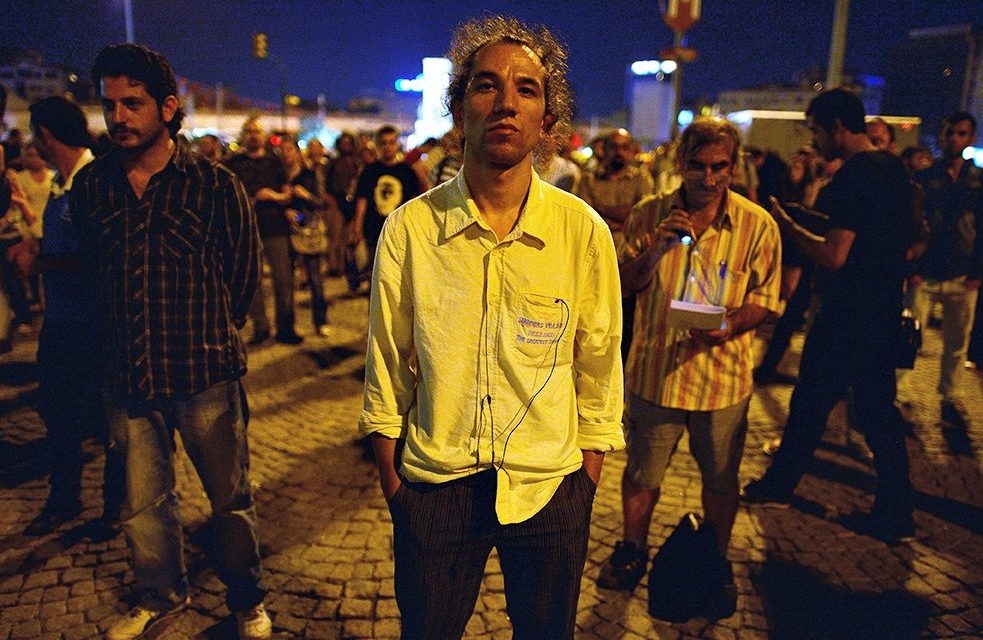

Nadine Berghausen: Mrs. Foellmer, you deal with the topic of “choreography as a medium of protest.” A well-known example of political protest is the action Standing Man in Istanbul – in Turkish Duran Adam – by the Turkish dancer and choreographer Erdem Gündüz. What is so special about it?

Suzanne Foellmer: Erdem Gündüz’s Standing Man was originally a response to the ban on public assembly imposed after the 2013 protests in Gezi Park in Istanbul. Gündüz just stood there, looking at the Atatürk monument and not leaving. Others later followed his example and stood next to him. The action quickly went viral on social media. Maybe it wasn’t extreme in expression, but in any case, it was a very much an act of resistance to which the police didn’t know how to respond. Because obviously it’s not forbidden to stand alone in a place. In this sense, it was a subtle action that subverted the ban on public assembly and demonstration. That it then suddenly began to spread at a media level, that it was shared through multimedia, that there were repetitive effects, and that it became a political action wasn’t originally in the power of the “standing man.”

NB: In most cases, protest is associated with a “louder” form of expression. Are standstill or slow movements even dance?

SF: The idea that standing can also be dance was formulated in the 1960s by Steve Paxton, one of the members of the Judson Church Theatre in New York. He called it “small dance.” Small dance because you don’t really stand completely still, because the body has to keep its balance. Some body part is always moving, even if imperceptibly. One example of this is the performance Constructing Resilience, which the Israeli choreographer Ehud Darash, who lives in Berlin, organized in the summer of 2011 in Tel Aviv. The occasion was protests against real estate price hikes.

NB: Do you believe in the idea of the so-called “Facebook revolution,” according to which the uprisings of the Arab Spring were possible only through the massive mobilization in social media?

SF: I think you have to take a closer look here. In principle, it can’t be argued that a protest is effective only because of new information channels. There were also effective protests in the days of analog media. Communication options such as Facebook or Twitter are particularly influential where access to public media is heavily controlled. But now even the social media are often under state control in autocratic regimes. Often they even allow activists to be tracked down. Here social media also have a downside. The question is always how power relations in these media are shaped.

This article was originally published in the Goethe Institut and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nadine Berghausen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.