Dedicated to the 35th anniversary of the Broadway musical “The Phantom of the Opera.”

It is known that the construction of the Grand Opera or the Palais Garnier in Paris inspired Gaston Leroux to write his famous novel “The Phantom of the Opera.” The building, which took over fifteen years to build (architect: Charles Garnier), became not only one of the biggest opera houses in the world, but also a structure filled with various unexpected technical solutions. The subterranean waters that appeared during the digging of the foundation pit were impossible to drain and so a large reservoir was built for fire safety reasons. The underground space is huge and organized in three tiers, two lower ones are deserted and represent genuine catacombs. The vaults are the main scene of action in the novel. The torture chamber, the boat ford and an island in the middle of the lake, where the Phantom hid himself, later were recreated on the stages of theaters where the musical played. The front staircase, the lobby of the theatre, the auditorium, the stage and backstage area, the dressing rooms – all worked in the novel as part of the story being told. So, the box number 5 in the first circle was reserved by Phantom himself, the chandelier in the auditorium fell as a punishment for the insubordination when someone did occupy “his” box.

The musical “The Phantom of the Opera” opened on Broadway in 1988 under the roof of the Majestic Theatre, which became Phantom’s home for the following 35 years. The Majestic Theatre was built according to the project by the architect Herbert Krapp, as part of a large entertainment complex which consisted of three theatres and a hotel. The first show to play on the stage of the Majestic Theatre was the musical “Rufus LeMarie’s Affairs” in 1927. It is one of the most spacious theaters on Broadway – a historical and architectural monument. After 35 years on Broadway, the musical “The Phantom of the Opera” is closing in May 2023. The Majestic Theatre – the house where Phantom lived, will be deserted and lose its mysterious resident. The Shubert Organization – the company that owns the building, plans on putting it on major reconstruction. The theatre will celebrate its 100th anniversary renovated, technologically modernized and just as hospitable as it has been to all the inhabitants of New York City and its guests for all these years. Perhaps, a memorable plaque will appear somewhere on the façade of the building, reminding all the passers-by of the West 44th Street that this theatre was the home to “The Phantom of the Opera” musical that lived there for 35 long years – the longest running show on Broadway as of today.

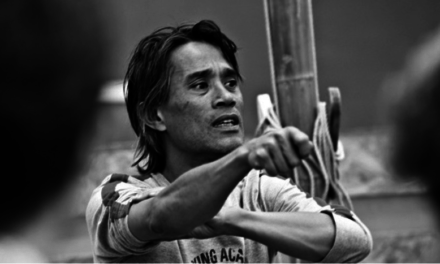

Photo credit Greg Mills.

Lisa Monde spoke to the people who did everything possible to provide a comfortable home for Phantom and shared their magic with the spectators.

Kenneth Kantor/ Photo credit Greg Mills.

Kenneth Kantor – a longtime and former cast member. He is considered to be the resident Majestic Theatre historian! Ken played three roles in The Phantom of the Opera over the years – Don Attilio, Monsieur Firmin and Monsieur Lefévre. And so, in over 15 years of being in the show, Ken never felt bored.

Ken was always proud to be a part of the Phantom family. He never took that good luck for granted. About a year in, he left The Phantom of the Opera to go do Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. After a year of performing in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Ken returned into the cast of the musical The Phantom of the Opera, which was “miraculous”. Ken was retired when the pandemic of Covid-19 occurred.

But when Broadway and the show reopened, he was asked to step in for a special 2-week run to play manager Lefévre again!

Phantom was favorable to Ken. For Ken, it was a tremendous honor being in the show and a great responsibility as well.

Lisa Monde: It is a rare situation for an actor, when you keep performing in a show for a really long time, playing the same character or a set of the same characters again and again. What was your approach? Did you try to make the characters different, to change them somehow overtime?

Kenneth Kantor: The main challenge was to go and do it in a fresh manner each time. The main role that I found the most satisfying that I played was – Monsieur Lefévre. I’ve played two of the three managers – Firmin and Lefévre. One can’t wait to get rid of the Opera House and one can’t wait to sell it. The challenge of a long run in a role like that is extraordinary and I really enjoyed that challenge.

LМ: I think it’s fantastic that you got a chance to play both the old and the new managers of the theatre. With both, Monsieur Firmin [as well as Monsieur André] and Monsieur Lefévre – the Phantom threatened you so many times, you’ve received multiple threatening letters from him – how did it feel going against the Phantom’s will?

KK: I thought it was very daring. The fun of the Lefévre role is the idea that he knows the whole story and can’t wait to unload the place. And it gives a very interesting spin on everything he says on stage because he knows what a lot of people don’t know and that’s a wonderful position to be in for a character on stage, where you’re knowledgeable and you have the opportunity to either expose or to keep the knowledge that you have. And that’s always fun.

LM: Were you scared of the wrath of the Phantom of the Opera as either one of the managers?

KK: (laughs) Not really. Lefévre is on his way out and Firmin – is so arrogant about the power of the Phantom that I don’t think the reality really hits him until the very end of the show. When, all of a sudden, everything collapses in front of him. Prior to that, he thinks it’s just a lot of nonsense. When he sees Buquet hanging there – that’s the shocking reality that I don’t think he really confronted prior to that. It’s a shocking awareness on the part of the character.

LM: Did you follow the Phantom’s orders and keep a seat for him open in the box number 5?

KK: I thought, as Lefévre – he knows everything, the expression that we used very often in staging was “He wants to sell the place and get outta Dodge”. He’s been through that already and now this enormous weight is being lifted from him, when he finally leaves and has sold the place successfully to Firmin and André. So, there’s an enormous relief on his part. The tension begins, as soon as he leaves, for Firmin. André takes it more seriously than Firmin. The biggest challenge in playing one of those two parts – Firmin and André, is to make them different. Because very often they seem like Tweedledum and Tweedledee. And to make each of these two characters unique in their own way, is a real challenge and certainly something that Hal Prince [the director of the show] was aware of. Trying to make certain that the characters are very different from one another and how can you make them different? I believe every effort was expanded to try to create that difference between the characters. Which brings me to the following point – our director, Harold Prince, had a very clear picture of what he wanted for the show to be. And he was occasionally at odds with the performers who were playing the roles, but, of course, Hal was always going to have the final word. It was Hal’s vision. And The Phantom of the Opera looks like no other show on Broadway.

Hal would establish the “perimeters” for the role – “This – is the character, and this – is where the character exists”. But within those perimeters – there was a lot of land. And I made it my responsibility to explore all of the territory within those boundaries. And, once in a while, you might wander beyond those boundaries and at that point Hal would go: “Hey, wait a minute. No. That’s too far, that’s not right. You’ve got to pull it back to this idea and follow this choice.” And having him constantly watching, and knowing what they want, clearly makes it very easy for the actor – there’s no obscurity.

LM: Since we are talking about the house where the Phantom lived, both the Paris Opera House which we see on stage and the actual theater – the Majestic Theatre… Tell me, how was it working at the Majestic?

KK: Working at the Majestic, if we talk about the theatre for a bit… I may be one of the few people in The Phantom of the Opera who has actually done another show at the Majestic. I have done a revival of Brigadoon that played at the Majestic Theatre in 1980.

LM: So how did the theatre transform then? How did it change once Phantom came into the building?

KK: Oh, it’s a very different place! When we did Brigadoon it was a lovely theater and a very warm show with an incredible affectionate cast – a very embracing experience. The next time I saw the Majestic was when I saw The Phantom of the Opera for the first time as a guest of Judy Kaye, with whom I’ve done a couple of shows. And she took us to see the musical and on our first backstage tour of the Majestic Theatre. Coming up to the theatre, it had a very different feel to it. They had put the gaslight fixtures outside the theatre and parts of the theatre had been painted black. It immediately became a very ominous place. Just walking into the theatre, it had a different tone when Phantom was there and it was… spooky.

But the Majestic had a tremendous history prior to even Brigadoon. It’s located on West 44th Street between 8th Ave and Broadway and that street is actually called the “Rodgers and Hammerstein Row” and there is a good reason for that. Because almost all of the Rodgers and Hammerstein shows played originally either at the Majestic, across the street at the St James or down the block at The Shubert.

And there is one location at the Majestic Theatre that is very interesting from the historical point of view. If you look at the stage from the auditorium, as you’re looking at the stage, on your left, there is a curtained off area that provides a staircase to the opera boxes and eventually leads you to the mezzanine…

LM: I guess, Ken is taking us on a magical tour inside the Majestic Theatre and sharing its inner secrets! What is so special about that curtained off area on the left side of the stage?

KK: You see, when the musical Carousel first opened at the Majestic Theatre in 1945, Oklahoma! was playing across the street, at the St James still.

And when Carousel opened, Richard Rodgers injured his back, commuting from Boston, where the show tried out, to New York. He lifted a suitcase that wrenched his back out but he, of course, wanted to be there on the Opening Night. However, he was strongly drugged because of the pain and yet he wanted to be there, nonetheless. So he was behind that curtain on the left side of the auditorium on a stretcher. He listened to the show, but he couldn’t see anything, because the curtain was closed – nobody wanted for people to know that Richard Rodgers was stretched out there. And he thought, in the drugged-up state that he was in, that the Carousel was an enormous flop and that it didn’t go over well at all! And it wasn’t until the very end of the show when the audience went mad, of course, that he realized that it was a successful show. You see, every time I get to the theatre, and I see that curtain, I think of Richard Rodgers behind it, trying to appreciate the show without being able to see it.

LM: Would you say that the Majestic is one of the richest theatres historically?

KK: Absolutely. There isn’t a single major musical theatre performer that did not perform at the Majestic. Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Bea Lillie – had shows there. It’s a large theatre but it’s not so large that a play can’t play there. Henry Fonda, Liza Minnelli stood on the stage of that theatre. The amount of shows that premiered there is striking. You just can’t escape the thought as you’re on the stage of the Majestic that that was where Richard Burton did Camelot, where Robert Preston originated the role of Harold Hill in Music Man. It is a very famous auditorium and they say that theatres enrich themselves by previous performances and if so, the Majestic is one of the most enriched theatres out there. And it’s also a very attractive theatre to play in, because it doesn’t have a second balcony. It only has one balcony. Selling the second balcony is always difficult and there are always open seats on the second balcony no matter how big of a show it is. But at the Majestic, because there is no second balcony, you can always count on a sell-out. It makes that theater a very exciting place to be. The audience’s reaction is so strong and they feel so close to the stage.

LM: I know that The Phantom of the Opera is a very demanding show when it comes to its technical equipment. Was it complicated, working with such a large set?

KK: The mechanics of moving a big show, and Phantom is a big show, in a theatre like that are quite challenging. Because when you exit stage right, you have about 10 feet and you’re up against the wall. Same on stage left. It’s a tight space. So where does all that scenery go? The Elephant from Hannibal, the Manager’s Desk, Christine’s dressing room? These are enormous set pieces. When originally Majestic was built, the scenery was not designed that way. It was mostly what they called the “soft scenery”, with drops and wing pieces. There weren’t a lot of three dimensional pieces. And with Phantom you have a tremendous amount of that stuff. So where does it all go? It all flies up above your head in the wings and the choreography of getting that scenery down so that it could come out on stage for its moment, then off stage and then back up again, so that the next set can come in – it’s very sophisticated. And that is one of the big challenges of doing Phantom at the Majestic. In addition to learning your show, you have to learn your backstage traffic so that you won’t get conked in the head with the scenery that’s coming in and you won’t be in the way of the stagehands that are moving things around. The wings are the terribly active locations. And it’s very easy for an actor to get in the way. So, once you’ve learned your choreography and movement patterns on stage, you have to learn the off-stage choreography that will keep you safe and will keep the show moving. And when a new person comes into the show, it’s a real necessity. Once you’ve learned the backstage choreography, you don’t dare vary from it.

LM: What is the safe space an actor can escape to at the Majestic Theatre? To get into character and prepare for an entrance, for example?

KK: The dressing rooms are located 3-4-5 flights up from the stage. So returning to your dressing room – is something that we really try not to do. So, you have to find these backstage areas to hide in. And when we did Brigadoon at the Majestic, underneath the stage we had sort of a green room area, so at least the actors could be stationed there, make some costume and wig changes down there, but The Phantom of the Opera has active scenery underneath the stage that comes up from under the ground. There’s no room underneath the stage now. So, trying to find that safe little corner for yourself is very tricky and just as important as learning your show.

LM: How did things change at the theatre throughout these years, with Phantom being there?

KK: Surprisingly little, and surprisingly a lot. The technology that was used when the show first moved in, was the technology that was state of the art in 1988. Now, it’s 35 years later. And bit by bit, the technology became more sophisticated backstage, in this day and age. The example that was used to describe it to me was that the computers that ran the scenery, that comes up from under the ground – the candelabras, the Paris skyline – is run by a computer which was state of the art in 1988, and by the time I left I was told that we could run all of that scenery off of a palm pilot. We didn’t need that heavy equipment in order to run the show anymore. So that’s a big change that no one would notice. The crew that we have with Phantom, because the show has been there for so long, is incredibly knowledgeable about how Phantom works at the Majestic Theatre. Without them there, we’d have many physical issues and interrupted performances. The crew was always able to step in and save the day without the audience ever being aware of it. The backstage crews are vital to the success of given performances. It’s really quite amazing in a situation of adversity, to watch the crew click in and save the show. Our crew always made us feel very safe backstage, because backstage can be a very dangerous place. And you never gave it a second thought at the Majestic because the crew people kept the show running so smoothly!

LM: Do you believe in ghosts? Did it ever happen that when things were going awry you felt like those were the doings of the Phantom?

KK: Usually the things that went awry were the doings of other actors on stage. Some of us dropped lines, which normally would not be a calamity but with a show that has music playing through it all, when something goes wrong, there’s no way to slow down the pace for a moment and reorganize yourself so that the show can continue on smoothly. Any errors that happen on stage, the challenge of dealing with them is doubled because the music just keeps playing and you have to stick with that music. I mean, a couple moments that I had on stage, other than of my own doing, which is a whole other story… was the one time we were doing the Managers Scene 1 – where all the notes are arriving. And the guy playing Raoul didn’t come on. Well, normally it’s not a big deal and you just adlib until the actor shows up, but the music kept playing and the words that had to be sung didn’t belong in your mouth. And so, what we had to do was to take what we knew was going to be said and turn that into what your character would seemingly be saying. But I never thought of it as being a Phantom Curse, as much as it was a Raoul Curse. I remember, as we were sort of rewriting the lyrics on the fly, so that we could continue to say what needed to be said, and putting it into the mouths of our characters who didn’t necessarily know what needed to be said, I looked down at the conductor, who of course wasn’t pleased with the whole thing but had no choice. She had to keep conducting. I looked down at her and she looked at me and she shrugged her shoulders and also had no idea how to resolve that problem. So we did the best we could until finally Raoul came on.

LM: Well, Phantom is not a big fan of Raoul’s so that would explain it somewhat…

KK: Yes! I wouldn’t say no to that. I’ve seen theatre ghosts; I’ve just never experienced them at the Majestic. They’re certainly there, I have no doubt about it, but they stayed out of my way. Phantom was never out to get us. But there were definitely a number of calamities, simply physical things, as well as the forces of nature. Once, on a dreadful matinee day, it rained hard, it was a torrent of rain and it broke through the ceiling of the building. And the stairs to and from the dressing rooms became waterfalls. That same day I was off stage – stage left, where the electrical connections are made and sparks were flying out of the wall because the water was dripping down. We didn’t know if we’d be able to do the evening show. And yet again, the crew saved the day, we did the show, without any interruptions. Our off-stage clothes were a bit soggy but other than that we escaped uninjured.

LM: Any issues with the complicated set pieces that you have in the show, perhaps?

KK: We had some issues with the boat. It moves wirelessly, kind of like a wireless car that kids play with and there is a joystick off stage that moves it and sometimes the boat just simply wouldn’t want to go, the trap doors didn’t open and close at the right time, and suddenly Phantom and Christine would have to walk through the water into his Lair. So, if you decide it was an actual Phantom that lives at the theatre playing tricks on us – why not!

LM: Since you’ve been with The Phantom of the Opera for so long – I know that the show meant a lot to you. You kept playing the same characters over the years, how did your characters change? Obviously, you were changing throughout those years, so my guess is, the characters changed a bit too, or not?

KK: I believe, when I first started, the first three months of the show I was just terrorized. Because I didn’t want to waste anybody’s time when they were putting me into the show. I spent a lot of time learning all of these foreign pronunciations of the names of the characters that I had to say, and I learned them all incorrectly. So for the first several months I really had to concentrate on what I was saying, when I was introducing the characters and what their names were. I had one notorious performance, when I was introducing Ubaldo Piangi and for some reason I introduced him and twisted his name. It was terribly funny and for the next several shows when I had to introduce him I was afraid I would do it again. Ubaldo Piangi – I introduced him as Adobo Pasquale. You know, you have to say something and that’s what came out, so he became Adobo Pasquale for the rest of the show. I think it was because that night I was making lamb chops and I used Adobo seasoning, I have no idea. But at least I said something. For the next week or so people would gather in the wings for my scene and were waiting for me to make another error along those lines.

Later, once I became comfortable, I thought the character could be funnier and so I started to play it in a more exaggerated manner, and I was quickly told that that’s not the direction I should go in. And eventually it really became a contest of wills on my part – never to do two shows exactly the same way. I hope the audience notices the difference. One of the stage managers complemented me on the fact that I was never boring and that it always seemed fresh when I did it. And it was an easy thing to do because when you looked around the stage, with the understudies on and the things being slightly different then they normally happen – I allowed that to enter into the reality of the character that I was playing. Therefore, I like to think that once I was comfortable within the perimeters of the character where he exists, I found that it was never boring, and it always seemed fresh to me and I don’t think it necessarily changed a lot, as much as it remained fresh.

LM: Now, how did the audience change throughout these years you think?

KK: I think they changed quite a lot. For many audiences that came, English was not their first language, and so while we have simultaneous translation for various languages, they’re not necessarily synchronized with what we’re doing on stage. And so occasionally, the reaction would lag or jump ahead of us, because of what they were hearing through their earphones. Also we had a lot of tourists that would come, and very often they had had a long day of sightseeing and they would come to see the show having had a very nice meal as well, and they would sort of doze off a little bit. So the audiences were sometimes on the sluggish side. It was always interesting to try to engage the audience early in the show. And we all had little moments where we would listen to their reaction and say “Oh, ok. They’re that kind of audience”. It became our responsibility – not to give them what they were expecting, but to somehow alter their expectations so that they could see the show that was intended to be presented. And in that sense, all through the run, the audiences were never identical, and there were some audiences that just sat there silently and there were other audiences that were right on top of things from the very beginning. And I think one of the most unusual audience reactions we’ve ever had – was that one time. The American political parties – the Democrats and the Republicans, are represented by animals. The Democrats are represented by a jackass, a mule, and the Republicans – by an elephant. The Republicans were having their convention in NYC at the time, and the Elephant came on during Hannibal and got an ovation. People who were there for the political convention were the Republicans. And I think it was the first and only time that the Elephant ever got a big hand. So you can never really outguess what the audience is going to do. We would always try to be aware of the various differences within the audience. I understand, because the closing has been announced, the audience’s reaction at the show right now is very much like when the show had just opened. The ovations are quite prolonged and extraordinary, and it’s a very exciting time to be doing the show. Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote a song about it – the audience is the “big black giant”. One night it’s a talking giant, one night it’s a sleeping giant, one night it’s a laughing giant. Every night you fight the giant and maybe if you win you send it off better than when it first came in. And I think that sums up the reaction of the cast towards the audience. They are always different and somehow it seems they get together in the lobby before the show and decide “This is what we’ll do to these poor actors tonight…” We’re playing off of the audience, always aware of their existence. They become part of the show.

LM: Now, is there a role in The Phantom of the Opera that you haven’t played yet but you always wanted to play?

KK: Yes. Alright, we’re talking non-traditional casting here – Madame Giry. Madame Giry is probably the most fascinating role in the show because, again, she’s sort of in the same position that Lefévre is in, but she gets all the way through the show. She knows so much more than anybody else on the stage. And what she decides to share and when she decides to share it, and how her reactions are to the various things that are happening in the show – make her an infinitely fascinating character. And if they could find a costume that would fit me, I would do it. I would even shave off my mustache to play Madame Giry.

LM: I find it interesting that… In the German musical Rebecca one of the main characters is the keeper of the mansion at Manderley – she is literally Madame Giry.

KK: Yes, as a matter of fact, Hal would describe Madame Giry as that character. And she is purposely dressed the way that Mrs Danvers is dressed in the movie. They tried to achieve the same thing that that character achieves in Rebecca, where she never enters the room. She’s just always there.

LM: And she is the keeper of the secrets, basically.

KK: Yes. And it was an image that Hal used. The similarities between the two characters are extraordinary.

LM: What would you like to add to conclude our interview?

КК: Not every musical on Broadway welcomes so many people to join it and welcomes people back as well. Making it a home for people – that’s what makes Phantom all the more special. For many actors Phantom is the one and only major credit and this moment is worthy of being enshrined. No show runs forever. The thing to focus on is the length of the run and the success of the run and what the musical has given people. Overall, it was amazing working on The Phantom of the Opera.

Photos Backstage/ PC: Greg Mills.

Ken told us about another secret – a special feature backstage: when the show first opened there was an actor in the cast – George Lee Andrews and he stayed with the show for decades. He started to collect pictures, resume photos of all the people who ever did The Phantom of the Opera. He framed them and put them up backstage. Eventually, there were so many of them, that he reduced them in size and put them up as collages, there were many frames – about 45 pictures in each frame. And when George Lee left, Ken took over and carried that tradition through. Backstage keeps the photos of all the actors that have ever done The Phantom of the Opera show. That is an enormous statement about the longevity of the show and Hal’s dedication to it.

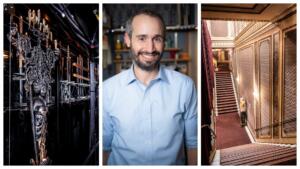

Greg T. Livoti/ Photo credit by Greg Mills.

Gregory T. Livoti, the Production Stage Manager

Gregory has been the stage manager at The Phantom of the Opera for the past 10 years. He is the person who solves whatever issues may come up during the show, who organizes the cast and crew and is ready to save the day, always.

Lisa Моnde: What are the most memorable moments that happened during the run of the show in your experience? Any mysterious, funny, hard situations that you had to get through?

Greg Livoti: The first one that comes to mind is the performance on the night that Phantom announced it was closing, initially. You know, it was a bit of a somber day. But at the very end of the show, in the last scene where we are at the Phantom’s Lair, where there is all that scenery – the candelabras, his throne and the organ… And in order to get to curtain call we have to clear all the scenery from the stage and there’s a lot of things going down into the floor and the trap doors closing… We had a malfunction with the scenery going down into the floor. As we headed into the curtain call. So, we essentially had holes on stage, where the company was supposed to take their bows. And we were worried at the safety of that. But in the moment, as I am assessing the situation, my first thought is “Ok, if we can’t get this cleared, we’ll have to cut the bows. There’s no way we can do it, the stage isn’t safe”. And then in my head I go “Wait! No. We just got some pretty bad news today and these people deserve this bow more than ever.” And so, with the other stage managers and the crew, we all thought quickly and creatively and ended up bringing this curtain in, that is somewhere between the front curtain and the first open hole. And then we quickly got word to everybody in the company – clear off the wings and everybody is going to go down… we’re going to do the whole curtain call on a narrow piece of stage. But we were putting a flying scenery piece behind the cast, so nobody was in danger of being near the open holes in the floor. But it was one of those moments where we had to make things work and figure out a way to do it… And bless the audience that day – it took us probably what felt like 10 minutes, it was really 30 to 45 seconds before we could finally get people onto the stage to start bowing. And that audience never stopped raucous applause and cheering. We knew that the audience wanted it, the cast – needed it, we had to make it work.

LM: Seems like the Phantom himself got upset upon hearing the news and decided to stay on stage… Any other occurrences that were not the Phantom’s doing?

GL: Yes, there was one day we had some massive summer thunderstorm and there were some drains on the roof of the theatre that were clogged up and it resulted into this overflow which was like a rush of water coming down the backstage staircase. During the final scene there was water dripping from one of the upper boxes in the audience. So, we thought – “Well, you’re down in the Lair and it’s wet and damp and all” – a true 4D experience. I’m sure a lot of people thought it was part of the experience when in reality we were trying to bail ourselves out from the water in the wings. I’m glad it happened at that point in the performance – we were almost done with the show. It was a scary moment for sure. Luckily, there was no massive fallout. And that happened within my first couple of weeks of working on the show. Interestingly enough, the first story that I told you happened at the end of the show’s run and the second one – at the very beginning for me. And in between, there was the 10 year-long span.

LM: You’ve been working with actors and have seen many actors play the role of Phantom over the years. How did that process work? How different were they from one another? Tell me a little about working with the Phantoms?

GL: The way we try to do this, when teaching the show, is – we allow our actors to explore the character on their own within the given perimeters. Many people played this role over the years. There is no type as such, there is no height requirement, or body type or anything like that, no specific requirements which need to be met in the same way for every person. We’ve had people of different sizes, shapes, people who have a darker resonance to their voice versus people who have a thinner component to the sound. Obviously, there’s the blocking to teach, but beyond that, everybody is going to inhabit the character in a slightly different way. We just want to say – “Here are the dotted lines and here are the double yellows.” We haven’t put in a new Phantom for a while, Ben Crawford, our current Phantom, has been with the show for a number of years now. But during each process of introducing the new character into the show, any character, I always find that I hear things in a different way, or I learn something new about the character just because of the way the new performers naturally express it or deliver it. That can be invigorating as well. Different people are going to bring different things to the role. Phantom has tried to embrace that over the years. And hopefully we’ve succeeded at least from the performer’s perspective. There’s always new things to be found.

LM: How would the Phantoms prepare themselves to step into the role? What kind of research would they do? Would they watch the movies, the performances that came before them, read the original novel? Was there a Phantom that was considered to be “the best” and others had to kind of emulate him?

GL: Everyone is going to approach their process in a different way. There are people who have read all the literature that’s out there, I’m sure they do a little bit of a YouTube research. Everyone has their own process. Actors will watch the show as part of their rehearsal process as well. We’ll work on some things in the rehearsals and we’ll say – “Tonight you’re going to watch the show.” To give them an idea of what it looks like from the front. I think what we try to say is – “You may see something different from what we’ve worked on in the rehearsal. What you’re seeing is somebody’s growth overtime – everyone is growing into the role and so there is no right or wrong. But the show we are trying to build for you is your version of the show. What you see someone doing in the video is not necessarily what has to be done exactly”. That’s not the most constructive way to solidify the work being done. And then there are other people who prefer to come in like a blank slate. Some actors sometimes ask if they can delay seeing the show until they’ve had at least four or five rehearsals. Because they don’t want what they see to impact their process. And that’s a very fair approach. We try to work with people while also working within the concept of how we need to get someone into the show in the timeline that it needs to happen within. I don’t think that the gold standard of Phantom exists. Each person brings something new. It’s subjective. People are going to relate to someone’s performance in a way that others might not for a variety of reasons.

LM: I wonder, if you’ve had that discussion within the cast and crew. Since the very first Phantom we’ve had was Michael Crawford and now we have Ben Crawford who is finishing up the run. How do you feel about such an interesting coincidence?

GL: It’s a nice bookend. And Ben’s been with the show for a number of years now. Most of the jokes were in the beginning when he first joined. Like “Oh, is the original Phantom your uncle?”. No relation, but it’s funny to sort of draw those parallels. And then, similarly, for a number of years there was a guy on the show whose name was Laird Macintosh and we used to joke with Laird as if he was our producer’s nephew [Cameron Mackintosh]. It is a nice bookend, to think that we had two gentlemen with the last name Crawford who started the show and, in our case is unfortunately, now ending the show.

LM: What will happen to Phantom?

GL: Well, when we got the news on the eight-week extension and an article came out – our producer was quoted as saying “Phantom will be back on Broadway”. When that might happen? Nobody knows. But it continues to have a life and be produced all over the world. I think what’s clear is that this piece resonates with so many people for a variety of reasons. Everyone has that part of themselves that they feel is ugly and shouldn’t be seen. I think that’s why it’s so universal – it’s a story of love, it’s a story of being “other”, in any way, however that’s interpreted by someone. I think when something is so universal as those two things – that’s part of the reason the show has been such a success. And, if you ask me, it’s a brilliantly constructed piece of theatre; music direction, design – all integrated in a really cohesive thoughtful story, everything is done on purpose. Nothing is left to chance. Every detail is accounted for. If you try to add up every little thing it doesn’t quite make sense but if you see it all as a whole – you don’t consciously perceive what is impacting your viewing. It all comes together and works together. How, for example, the black paint around the proscenium draws in the audience, the details of what is onstage and the details in the house as well. It feels timeless, because there’s nothing out there like it. And I hope, for future generations, that people will continue to discover it anew. Some of it will be up to folks like us who were able to experience it and share it with whoever might not be familiar with it, until it does come back again.

LM: Do you think the musical The Phantom of the Opera should be commemorated somehow? Like a plaque on the theatre which would state that Phantom ran there consecutively for 35 years – it is a huge deal, it is the longest running show on Broadway. Or maybe a monument to Phantom or something like that?

GL: I think it’s a really nice idea. This is the longest running show in Broadway history, at certain point something is going to surpass it by something that already exists or something that is yet to be written. I think there’s a nice way to commemorate the work that has been put into this show over the years, something like that on the façade of the theatre, with that iconic mask. To say “This was here, it happened. This was important”. Because as time goes, things become less important the further away you get. That’s human nature. But if we can be reminded of it, with all the work that we put into it, and the labor of so many dedicated crew members, performers and staff… I mean, from top to bottom, people have done everything they possibly could to make this show the best it could be. So to see some sort of acknowledgement of that work would be nice.

LM: Many crew members have already told me that Phantom has been favorable to them and they haven’t necessarily encountered him at the Majestic. Have you had an experience or a feeling that the place, the theatre you worked at was somehow haunted?

GL: Where it can feel really weird is if you’re one of the last people leaving at the end of the night. Most of the lights are off and there’s just the light on stage – the Ghost Light. It is strange to be walking seemingly alone in the huge empty space of the theatre. It’s relatively dark and these are old buildings, they make noises. But when you hear some sound from several feet away, it feels strange and spooky.

LM: You’ve seen the show many times, as part of the process, from the stage, from backstage and from the audience. How did the audience change throughout these years, their reactions, their perception of the show?

GL: The show has changed over the years, because the audience has changed. I think we, as viewers of any content – live, television, – we are ready for things to unfold faster. The attention for a slow developing story is not as reliable. There are some things that we’ve done with the show to, not modernize, but to naturalize the performance a little bit. So that it doesn’t feel lethargic or too slow. Even though the tempo doesn’t change. If our delivery is more natural, it lands itself better with the audience. That was some of the focus when we restarted. You know, there’s opera within the show and opera is presentational. The bulk of what has happened over the years, while we still have a lot of these operatic moments, we are interacting with each other more as people in a world and we are interacting with the audience more.

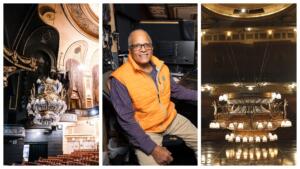

Alan Lampel/ Photo credit by Greg Mills, Photo of the Chandelier by Joan Marcus.

Alan Lampel – Head Electrician (since day one!) / Head Lighting Tech

“I’ve spent over half of my life in that building.”

Alan Lampel

Alan Lampel is the Head Electrician and Lighting Tech at The Majestic Theatre. He was responsible for wiring the legendary Chandelier that would fly over Broadway audiences each night and has been keeping the lights on for Phantom for 35 years.

Lisa Мonde: You are a veteran of this production, a man who can be considered the longest active contractor in history of the show and probably of Broadway in general. You’ve been with Phantom for 35 years. How do you feel? Now that Phantom is closing in May.

Alan Lampel: It’s been a long run indeed. I worked on this show probably six months before it loaded in, because I actually had the amazing opportunity to work in one of the shops that built this show. So many items came through my particular department, which was called R&D (Research and Development) at the time. This particular shop was very well-known for its work in that field. So, we took great pride in, for instance, the chandelier itself. We were one of the four shops to participate in its construction. I think we were the second shop, wiring the chandelier, adding multiple kinds of insulations, and then it had to go off to another shop to be outfitted with all the globes and beads. I had the opportunity to witness multiple shows from this perspective. It was a very exciting time for me. But this one was jam-packed with fun goodies.

LM: Since you’ve already mentioned the chandelier, I have to ask – I’ve heard that it weighs over a ton – is that true?

AL: Well, it weighs a little bit more than a ton, somewhere between 12 hundred and 14 hundred pounds. It really does need to swing well.

LM: How many chandeliers were there, throughout the run of the Phantom?

AL: This chandelier is the original chandelier, placed here in 1988. We have maintained it very well and it has gotten a few updates over the years. There were six chandeliers in total in the United States (New York and another that was for the National sit-down production in Los Angeles and San Francisco – the Christine Company). Then there were two of each for the two National touring companies (Raoul & Music Box Companies). And I oversaw the wiring of all six of them.

LM: I guess you can be called the Chandelier Master of The Phantom of the Opera!

AL: (laughs) Well, that’s a very kind title. I know every bit about this chandelier, that’s for sure. The others were basically similar, just laid out by different people. And as the years went by, the dimming got better, different quality and all. The last two were made out of aluminum, as opposed to the first four that were steel. The first one was the heaviest, I’m sure. She was nicknamed “Ruthie II” after Hal Prince’s [director] assistant, Ruth Mitchell.

LM: And Ruthie II was on Broadway all these years, correct?

AL: Yes.

LM: How did things change when it comes to the operation of the show?

AL: The electrics have evolved quite a bit, though the lighting design is pretty much the same faithful design since day one. For instance, we’re on our third lighting console. That’s what I run the lights on every night for the performance. The first one was this huge piece of furniture — it was on wheels! It had to be taken apart and reassembled in the space that I occupy still in the house. The second console could fit on top of a table. And the third one takes up even less space and is so much more efficient, robust and worry-free. Technology has come a long way. The first one had three floppy disks. One change happened during a live scene, in the middle of the first act. That was a bunch of years of holding your breath. Because, in fact, there was only space and time to load it twice. Otherwise, the next cue was coming up and it was in the same scene. To have this change in the middle of the scene was just hair-raising. It would have been much easier to do it between scenes.

LM: May I ask you which scene that was?

AL: The middle of Managers 1 – the door openings. I would never forget it. It was between the second and the third door openings. That’s a busy scene!

LM: So, you are responsible for all the lighting design happening in the show?

AL: Yes, day in and day out. I try to do my best to keep the lighting design crisp. It’s a very small stagehouse and the show is very tightly hung. It took us all a while to make things work smoothly.

LM: The lighting design is a huge part of any show, but especially for The Phantom of the Opera. It sets up the atmosphere.

AL: I believe that the lighting design is very important in any show, and this show is no exception. Quite frankly, there will probably never again be such a rich show, lighting-wise. There is a certain fleet of lighting units that are probably never going to get used again on Broadway when we close. I have been maintaining what is called the Altman 360Q diligently and respectfully as the shop weened themselves of this very unit over the last 10 years. It truly makes a beautiful, rich light that will never quite be seen again in this format. I love the lighting design on this show.

LM: Have you introduced any new lighting equipment into the show, since now the abilities are different and the progress has moved on?

AL: That is exactly what we did for the reopening. I call them “the new toys”. They happen to be the only LEDs on this show. We introduced new lamps called the Luster II by ETC and it enables the designer to color the light electronically from within. Those have made my life easier because instead of having to maintain some old scrollers, called Color Ram’s, that are now obsolete also. And then, our light-curtains – that’s a whole other story. There were two particular batons of lights, “X-rays”, as we call them – they did a lot of things, they moved, did live sweeps of actors – those were all operated by myself, live on the console. That was really exciting all these years, because it was still live in the New York show, but on the subsequent touring shows it became an automated kind of thing. But it was easy for a number of people to be out of sync and have the light be behind or ahead of the actors. In New York I was able to do that live, and you didn’t miss them ever. I resisted those upgrades in New York to favor the manual attention for years until the reopening. These new lighting units come from a German lighting company, GLC. They are fantastic. They do electronic controlled color as well, have a variety of beautiful colors and you can even build any color you want. The associate lighting designer, who was in charge of the reopening, had a lot of fun with those, but it was also challenging using the new equipment, because she had to create the similar effect, lighting-wise to duplicate the original light curtains. So we did that, but also came up with some new fantastic and unique colors. It’s dazzling.

LM: What was your favorite lighting trick in the show?

AL: My favorite scene is the Lair Scene. The trick there, is that it’s done so beautifully with so few lights. “Minimalist lighting” I call it. Andrew Bridge [original lighting designer] did an amazing job. The way we use the green for the water flicker and the amber to represent the candlelight – it’s really something. And then you layer on these four delicately worked Follow Spots. It makes the scene just beautiful.

LM: I love the lighting in that scene too. You mentioned the Follow Spots, is there a person moving the Follow Spots or are those automatically operated?

AL: No, not automated at all. Each one is moved by a person. It takes a lot of experience to do this well.

LM: So how many times have you seen the show?

AL: I’ve probably seen Phantom more than anyone else in the world. There’s no one that’s kept a job like mine, looking at the show from the front, for this long. Even in London they change out these jobs more often than we do – it’s a different labor framework that wouldn’t allow a person like myself to keep this job for so long, it just doesn’t work that way there. I’ve got a bunch of records, certainly for being a stagehand – the longest sitting stagehand since the original show. And holding the same job for the entire run.

LM: That’s what makes Phantom so special, among other things. It becomes a home for many people who work on it and Phantom welcomes people who have been working on the show in different positions back, over and over again. Which is quite unusual for Broadway shows in general.

AL: That’s true.

LM: Now, did you encounter the Phantom at the theater? Was he in your way every once in a while?

AL: No, I was lucky. Because he lived backstage, and most of my time was spent out in the front of the house, at the console. So running into him was not in the cards for me.

LM: Since the show is so complicated, when it comes to the set and the multiple cues that have to happen – lighting and sound and the operation of all the above mentioned, has the show ever been on the brink of stopping?

AL: I can knock on wood and say that the show has never had to stop for my department. When I think of all of the loadings of that disk, it’s amazing that I never had bigger issues with it. There were plenty of moments of really heavy sweating in those days.

LM: What was your favorite part of the show? Perhaps a specific scene where you had fun with lighting and were especially proud of your work?

AL: The Overture – the strobes that play throughout the overture – was something I used to do manually. Which certainly added to my show’s excitement. That was my part of art, it was my live, nightly, artistic contribution to this show. No show’s overture was ever the same. This contribution came along with a musical sensitivity. I learned to love it, so it became my light-music moment. I tried to convey a feeling. My original words to describe the atmosphere, the goal, when training a sub were – “spooky B movie and intense drama.” Of course, they all had their own interpretation of that, and I would sit back and watch what they came up with. When we put in the new strobes three years ago, we now had a console that could record what I’d been doing live. I really took this as a compliment to the faithfulness of my contributions. The cuing of that sequence is now initiated by the sound console, in fact, so that it is in complete sync with the orchestra and the overture’s execution, needing to be musically matched all the way through. It’s moving and brilliant. I would have liked to embellish the Lair Scene as well… But I guess, one doesn’t always get their way. Now that the Overture is recorded on the console, I don’t have to do it manually anymore — I can sit and watch it happen. I love how I was able to create that “shocking moment” with the help of lighting and music. But now I have no control over it – it’s a different experience.

LM: What would be your parting words for Phantom?

AL: I should have been retired a year ago, but because of Covid-19, I needed to regain a bit of funds that I had to tap into, as many of us had to do while we were out. And when we were told that Phantom was coming to its closure, I was very happy to know that I would be able to be there till the end. I’ve been replaying just how it’s going to feel as these days count down. I’ve put a lot of love into the show. I’ve spent over half of my life in this building. That’s a weird thing to say. But it’s been fantastic and how better could you write a scenario like that for yourself?

LM: True. You’ve become part of the history. You made history with Phantom.

AL: It has been a wild ride.

Hugh Barnett/ Photo credit by Greg Mills.

Hugh Barnett – the House Manager at the Majestic Theatre

Hugh has been the house manager at the Majestic Theatre for 10 years with The Phantom of the Opera. He used to manage other Shubert Theatres and was fortunate to attend the opening night party of The Phantom of the Opera in 1988 at the Beacon Theatre. He was the house manager for the original production of the Chorus Line!

Lisa Мonde: You’ve been with Phantom for quite some time, and you know how Phantom is today – how did the show change throughout these years and how did the audience change?

Hugh Barnett: One of the joys of being associated with this show has been that the producers – Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cameron Mackintosh – as well as the Shuberts, used large sums of money to keep the show in such stellar condition. I was lucky to start my career in the mid 80s in the original production of the Chorus Line. So I’ve been fortunate to work in long-running shows. It’s a lovely feeling to be associated with the show that is as crisp and just as good, not just on special occasions, as it was on the opening night. People in this production are very enthusiastic and keep the show in a stellar condition – so in regard to the level of production – not much has changed.

LM: You are the person who welcomes the audience, when they first come into the theater. In your experience, how has the audience changed throughout this time?

HB: When it comes to the audience – it’s a show for all generations: parents, kids, grandparents… Since now the house managers on Broadway wear nametags, people that come in, know who I am, and a lot of people have approached me not to complain but to express their joy at attending the show and tell me how many times they’ve seen it.

LM: So you’ve been the manager of the House where Phantom lived all these years. How was it – being the manager for Phantom?

HB: I always refer to it as a happy show. It’s a date night show – straight and gay, it’s a family show, it is a show that people come to propose, for whatever reason, it is a show that they bring very little children to, and it is a show that very elderly come to and everything in between. It’s a joy to be there because people are happy. People are coming to be entertained and this is such a lush show, they are getting a beautiful, full out, well-rehearsed production. To such an extent that one wonders if we’ll ever see anything like that on Broadway again any time soon.

LM: Very true. Now, have you received any letters from Phantom?

HB: No! But Phantom Fans – PH “Phans”, expressing their gratitude and joy for the show and every so often thanking the theater staff and appreciating their efforts to accommodate people.

LM: Have there been any major issues during the run of the show, like the set malfunctioning etc.?

HB: No doubt, there have been many things over the years, there were a couple of times when the gates and the candelabras didn’t come up or the boat or the fog didn’t work. And there have been instances when the chandelier didn’t go down.

LM: Now, when that happens, do you blame it on the Phantom?

HB: (laughs) No doubt that there is a Phantom somewhere in the system, yes.

LM: But it seems like Phantom has been favorable to everybody in this show.

HB: Yes, without question.

LM: I know that when Phantom moved in, a lot had to be done at the theatre to accommodate a show with such big set pieces: the area under the stage had to be completely transformed to have it all working and functioning and for storage. What modifications will be happening at the theatre when Phantom moves out?

HB: The theatre will be completely redone. They literally had to jackhammer and go below the concrete floor which was there, under the stage. That was done to accommodate the gates, candelabras and so forth. So that area will be filled in with concrete and smoothed out. There’s a lot in that building that needs to come out.

LM: Since Phantom has been the longest running show on Broadway. Is there going to be anything that commemorates that? Will there perhaps be a plaque installed on the theatre?

HB: I don’t know anything definitively, but… We can just go down the block to the Shubert Theatre and there is a commemorative plaque for Chorus Line. I have to imagine that a similar plaque would be put in the Majestic at some point.

LM: Are there any plans to create a room or a little exhibit at the Majestic Theatre, where there would be some kind of memorabilia – installation for The Phantom of the Opera once it’s renovated?

HB: It’s an interesting idea. It’s shocking but in the vast majority of theatres on Broadway there isn’t an inch of room left for anything. Like when Phantom came to the Majestic Theatre – it is jam packed backstage. The choreography behind the choreography, to get the people onto the stage, is amazing because if someone is in the wrong place at the wrong time – they may cause a major jam up, or just get run over. And at the front of the house there just isn’t any space.

LM: What would you like to say to conclude our interview?

HB: There are many stories to be told. Times 35 years, hundreds of people. Many people, myself included thought that Phantom would just be there. And that it would be considered almost like the Statue of Liberty. That when you come to New York, you come to Broadway, you see the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building and The Phantom of the Opera. I’m happy to say it has become part of the official “New York experience”.

The Ghost Light. Photo credit by Greg Mills

A special thank you goes to Mr. Michael Borowski, the press representative for The Phantom of the Opera, whose help was invaluable in the process of preparation of this article and acquiring the photo materials. I hope that with Michael’s assistance, our readers were able to experience an unforgettable journey into the House where Phantom lived. And his name was Erik.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lisa Monde.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.