The playwright

“I spring from ministers, murderers, rebels, addicts, closeted queens, soldiers, singers, and blue-collar mill workers.”

This confession opens playwright Gabriel Jason Dean’s artistic statement. It ends with this vision, “Though my subjects are sometimes provocative, I don’t see myself as a provocateur, but instead as an architect of questions. [. . .] As theatre-goer and writer, I crave transformative work that gnaws at my bones for life.”

How can one resist such a vision?

Dean’s revelations inspired me to explore his much talked about drama, Heartland, which takes place in Afghanistan and the U.S. Having taught at a university in neighboring Iran, I was impressed by the expansive knowledge of Islamic culture and modes of Afghan intercultural interactions that enriched his play culturally.

Heartland synopsis

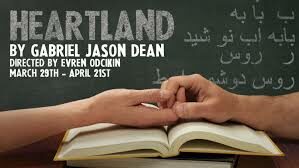

HEARTLAND poster, Interact Theatre Company, Philadelphia, PA, March – April 2019.

Set in both the U.S. and in war-torn Afghanistan, Heartland shows Harold, an American professor, now growing toward senility. He gets visited by Nazrullah (Naz), his adopted daughter’s Afghan boyfriend, a young mathematics teacher, whom she [Geetee] fell in love with while they were both teaching in their country of birth.

Through flashbacks, we see the young American woman trying to adapt to life in a Muslim society, while her boyfriend tries to absorb as many Western values as he can without giving up his Islamic beliefs.

Heartland shows the dilemma of good intentions on both sides of the ideological divide, leading to major problems. For example, years earlier, the professor helped write CIA-created, pro-Jihad textbooks to fight the invading Russian forces that led to the brainwashing and the subsequent death of many young Afghans.

Nazli Sarpkaya as Afghan-born American Geeta getting photographed

by Yousof Sultani as her Afghan boyfriend. Photo by Seth Rozin.

A generation later, the Muslim teacher, very much in love, took a Polaroid photo of the Afghan-American woman that got into the hands of his uncle, who killed her. The young Afghan devotes his life supporting the deteriorating father of his girlfriend in the U.S.—with a most unexpected ending. The excitement of the action—moving from one culture to the other, heightened by the frequent use of Dari—left the audience enthralled. One of the secrets of this moving and eye-opening drama?

Dean, an experienced and successful playwright who almost always works with a dramaturg, had listened closely to his cultural consultant, Afghan-born Humaira Ghilzai. Her work extends beyond just making sure things are culturally authentic. He co-operated with her practically from the beginning, marrying her intimate cultural knowledge with his dramatic talents.

Afghan-born cultural consultant Humaira Ghilzai,

dedicated to bringing people together across cultures. Photo courtesy of H. Ghilzai.

No matter how experienced American playwrights, if they write about characters in another culture, such as presenting life in Afghanistan, a traditional Islamic society—they need more knowledge and research than many a play based in the U.S.

Hollywood, with significantly more money available than the theater world, tends to hire the best experts to advise a writer on every nuance of another culture. Unfortunately, not everyone can afford to work intensively with a cultural consultant.

Dean, while a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University, won their $83,000 grant and, out of that fund, hired Afghan cultural consultant Humaira Ghilzai to work closely with her throughout the evolution of the script and all four world premieres—a kind of cultural rug weaving.

Four examples of American-Afghan cooperation on Heartland

1. To strengthen a pivotal scene, Dean needed to find out details about the infamous CIA propaganda school books for Afghan high school kids—textbooks which, after the defeat of the Russians, had fallen out of favor. These English-language schoolbooks had been used to turn young Afghans into a kind of underground resistance group to go all out fighting the occupying Russian forces—leading to many deaths in Afghan families.

Through her connections, Ghilzai actually found original copies of the CIA textbooks in Kabul. Dean, supported by the evidence, integrated references to those books into his play and showed the disastrous consequences that impacted the lives of all three of his characters.

2. Ghilzai became a bridge-builder between the playwright’s way of expressing something in English and the way Afghans would speak. She would offer several alternatives. After lengthy discussions, Dean would re-write the dialogues to make them even more authentic and natural.

3. To help non-native speakers of Dari, Ghilzai also created all of the Dari transliterations so that the actors could pronounce them easily.

4. During each of the four world premieres in the U.S., she coached accent, posture, and helped with costuming choices.

Looking at the script from an Afghan perspective

Video of Humaira Ghilzai interviewing Khaled Hosseini, author of the best-selling novel THE KITE RUNNER, which caused a furor in Afghanistan when the movie came out.

In a recent interview, Ghilzai presented her way of working with playwrights and people in the theater arts world and with Dean, in particular:

“In theatre consulting or any consulting project [. . .] you don’t give your opinion, you don’t move your own agenda; you help the client fulfill their goals. [. . .] my job is to bring cultural authenticity to their vision. [. . .] My job is not to censor anything.”

“[. . .] my job is first to set a scene for the world we’re portraying, and then I go on to help the costume designer, set designer, music artists, and cast create that world accurately.”

“We did everything by email and phone until maybe a year ago when we first did a Skype call and we met each other face-to-face.”

“Gabe [. . .] was very collaborative and he not only sought my input but really tried to understand more about the culture on his own. I would throw out ideas [. . .] and [. . .] we would discuss [them], and then it was up to him to decide if he wanted it in his play.”

“Once in a while, I’d see him throw in a line that was a little bit of an inside cultural joke, which showed to me that he really got Afghanistan and its people.”

Interview with Gabriel Jason Dean, the intercultural playwright

Playwright Gabriel Jason Dean. Photo by Jeremy Folmer.

Henrik Eger: Overall, there seems to be a tendency in U.S. theater to focus mainly on themes and characters from an Anglo-American perspective. What made you look way beyond U.S. borders and probe deep into the heart of conflicted characters, here and abroad?

Gabriel Jason Dean: Ultimately, this story is an examination of what it means to be an American. I am obsessed with that subject. I am interested in the stories we don’t tell and why. We have a history that we must face, warts and all, and the play puts a small part of that history forward.

So, I went where the story demanded, and I did the research and hired Humaira to help me make sure that what I was presenting was accurate. I think it is wrong-headed to believe that any writer can and should only write about their own specific identity.

Henrik: None of the traditional rankings of The 10 most important American [most widely performed] plays deal with anything outside the United States. How could American playwrights tackle subjects that deal with another culture sensitively and authentically?

Gabriel: As writers, we ought to be able to write about anything that sets us on fire. However, if the subject is outside our own experience, then we must do the research to the point of exhaustion—but there is only so much research one can do. Having one or more collaborators who have “lived experience” of the culture and of the place is extremely important when writing outside our own lived experience.

Henrik: Tell us about the development of Heartland, especially the input of the PlayPenn directors, the creative team, and the actors who stage-read your version in Philadelphia two years ago.

Gabriel: The play has grown immensely since the PlayPenn draft, and much of that growth was a result of the time I spent on it at PlayPenn with director Ed Sobel and dramaturg Kittson O’Neill. When I came to PlayPenn [new playwrights, see “Everything you always wanted to know about PlayPenn, but were afraid to ask”], I was still searching for the beating heart of this play, and through many rewrites while there, I found it.

Henrik: Once you finished your PlayPenn version, a number of theaters showed great interest in Heartland and, eventually, began premiering it.

Gabriel: I went on to continue to work on it through development with director Pirronne Yousefzadeh and Geva Theatre Center. I then shaped it further in anticipation of the first production of the National New Play Network Rolling World Premiere.

Henrik: I rarely, if ever, heard from writers about the impact of cultural consultants on their work. You seem to be one of the few playwrights willing to address this issue.

Gabriel: Thank you. Humaira, my collaborator throughout all of the many iterations, shaped the Afghan authenticity of this play tremendously.

Henrik: I saw the first and second staged-reading version of Heartland and liked them tremendously. However, now it has grown even further into a world-class drama. What were the main changes you made since those PlayPenn days, in addition to the four intercultural items (above) that you and your Afghan consultant had worked on?

Gabriel: First, I changed the character of Geetee from Greta—a domestically adopted daughter. My original impulse was to make Geetee Afghan, but I pulled away from that, because the Western concept of adoption is not something that actually exists in Afghanistan. But it simply wasn’t working for the story or the character, and so I endeavored to figure out a way that could make feasible her adoption by Harold [the U.S. professor who accepted the task of writing the English textbooks that would encourage Afghan students to fight the Russians].

What I actually settled on connected my characters even more to the CIA-commissioned textbooks.

I also removed all potential associations of Nazrullah to the Taliban. It became increasingly clear to me that I didn’t want him to even remotely be considered a terrorist in the audience’s mind. In the PlayPenn version, his uncle was affiliated with the Taliban, which made Naz affiliated by association. In the version you saw at Interact Theatre Company, his uncle Bashir is simply described as “motahasib,” or “traditional.”

Henrik: Which Heartland scene grabbed you the most?

Tim Moyer as the senile professor and Yousof Sultani as his best friend near the end of the professor’s life. Photo by Seth Rozin.

Gabriel: The scene that I knew would exist from the beginning would be the final scene with Harold [the aging atheist] and Naz [the young Muslim] praying together. I knew I wanted to show some kind of complex love and understanding between the two men.

The rest of the play gets us to that point. I’m not as interested in characters who tear each other apart.

Henrik: Most characters from the Islamic world in American drama and film get portrayed as rather one-sided, often unsavory, and dangerous characters. What did you do to avoid stereotypes, in addition to working with your cultural consultant?

Gabriel: One of the goals of this play early on was that I wanted to write a good Afghan character: somebody who was good at heart, flawed in the way that we all are flawed, but decidedly not a terrorist. Someone who had a healthy relationship with Islam. Not someone who was a victim and felt completely downtrodden.

So, the character of Nazrullah was born in rebellion to a lot of Muslim characters that I’ve seen portrayed in other plays. That was very important to me.

Then I thought, “Wait, am I doing this out of some White Saviorism?” I worried about that. I worried Naz was too good at times. But now, having thoroughly developed this play and this character and having seen the effect Nazrullah has on Muslim audience members, I think I’ve done the right thing.

Henrik: With the help of your Afghan consultant, you managed to reduce the lengthy final prayer of mourning while keeping the scene’s Islamic authenticity intact. As a result, we experienced deeply moving moments that had many of us in tears.

Gabriel: We used a shorter version of Fajr [the first of the five daily prayers], one that might be spoken by a recent convert. We opted to do only one rakat [the prescribed movements and words followed by Muslims while offering prayers] for the sake of theatrical timing. I never would’ve been comfortable making that choice on my own without Humaira’s input and that of several other Muslims.

In the Philly production, Yousuf Sultani, who is Afghan and was raised in a Muslim household, was doing a version of the prayer that was most comfortable for him. In instances like this, I defer and get out of the way to let those who know it firsthand show me.

Afghan authenticity versus violence-oriented U.S. producers

Henrik: Having taken the Afghan hurdles with your cultural consultant, what did you experience with American producers?

Gabriel: So many people have wanted more “drama” from this play—literally more bombs, more allusion to the conflict happening around Geetee and Naz—but I find that critique of the play intellectually and emotionally disappointing. I’m just not interested in that kind of play here. This is a quiet story about what is unsaid.

I had numerous meetings and calls with producers—all older white men, I might add—who desired that the play have more bombs and war. Those were challenging moments, but ultimately, I didn’t submit to that view of the play. I just waited for the right producers to come along.

Henrik: What would you say to directors and producers to help them overcome their concerns?

Gabriel: I often hear that this play is difficult to cast. Let me assure you, potential producer, it is not! After five productions and audition processes, I have a large list of excellent potential Nazrullahs and Geetees.

And producers often fret about the frequent use of the Dari language in the play. Rest assured, I have pronunciation recordings that are available for use.

Henrik: I think so highly of Heartland that I would like to see it translated and performed abroad to open up hearts and minds around the globe, including the Islamic world—whether as a play or as an international film, which could become available to many more people, irrespective of external and cultural borders and restraints.

Gabriel: I would love to see all of that happen as well! From your mouth to god’s ear.

Audience responses to Heartland

Henrik: Tell us about your experiences with audience members who saw Heartland, especially those with an Afghan or Islamic background.

Gabriel: For example, at Geva Theatre, they bussed in high school kids to come to see it. I remember being there after one of the matinees, and one of the students, a young boy, came up and said, “Thank you. This is great. I’ve never seen a guy like that on stage.”

He was talking about Naz, you know? Because every time this kid sees somebody who looks like him on stage, on film, or on TV, they’re not playing a character like this. I was like, “Okay, mission accomplished. My job here is done.” I love the character of Nazrullah. I love him so much.

At a talkback at InterAct, an Afghan man in the audience said the play was a true representation of Afghanistan and that he wished more work like this existed in the world. He told us all his story:

He walked nearly 2,000 miles to escape the Russians when they invaded in 1979. Eventually, he came to the U.S. as a refugee—something he couldn’t do today. He is now a doctor living in New Jersey. I hope more people like him get to see this play.

Henrik: Gabriel jan*, tashakor, many thanks.

*Jan (Persian: جان) or Jaan is a Persian word originally meaning “life” and “soul,” also used as a name with extended meanings like “dear” or “my friend.”

Dean’s plays include In Bloom, Qualities of Starlight, Terminus, The Transition of Doodle Pequeño, and Heartland. He also authored books and lyrics for the musicals Mario & the Comet and Our New Town. His screenplays include Pigskin and D’Angelico.

Dean’s scripts are published through Samuel French, Dramatic Publishing, and Playscripts. He is on faculty for Spalding University and Visiting Writer in Residence at Muhlenberg College. MFA: the University of Texas-Austin, Michener Center for Writers. He grew up in Chatsworth, GA, and currently lives in Brooklyn, NY.

To follow playwright Gabriel Jason Dean, visit his website at www.gabrieljasondean.com.

For more information on Humaira Ghilzai’s work as an Afghanistan Cultural Consultant, visit her website at www.humairaghilzai.com. To learn more about Afghan Friends Network, check out www.afghanfriends.net.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Henrik Eger.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.