Why are thespians the world over so drawn to Waiting for Godot, that for many older actors playing one of its leads is as much a matter of professional pride as playing Hamlet is for younger ones?

And why, in a poll by the U.K.’s National Theatre, was this 1953 Samuel Beckett work voted the most significant English-language play of the 20th century?

In a unique upcoming bill at Kanagawa Arts Theatre in Yokohama, audiences will get two distinct, made-for-Japan opportunities to ponder these questions and more, as director Junnosuke Tada stages two versions of the absurdist drama — one set in the Showa and Heisei eras (1926-2019); the other in the newly opened Reiwa Era.

In both versions, however, the story remains the same as two men named Vladimir and Estragon, who call each other Didi and Gogo, eagerly wait for Godot, about whom they seem to know nothing. Punctuating their speculations about Godot (who Beckett insisted was not God), and other odd exchanges, a pair named Pozzo and Lucky — who may be master and slave — briefly pass by, while in the play’s only other role a boy tells them Godot won’t come today, but will tomorrow. In fact, Godot never appears.

Perhaps it’s because Beckett left all those unknowns that so many dramatists are attracted to this work he described as a “tragicomedy in two acts.” Certainly they must relish a challenge, because the playwright insisted that no musical effects could be used — and not a word could be changed from the script he wrote.

Despite this, 42-year-old Tada, founder of the cutting-edge Tokyo Deathlock theater company, is set to present his double bill with the Showa-Heisei leads played by Hiroo Ohtaka and Takayasu Komiya — both around 60 years of age — and Reiwa’s leads by Sennojo Shigeyama and Gota Watabe — both in their 30s.

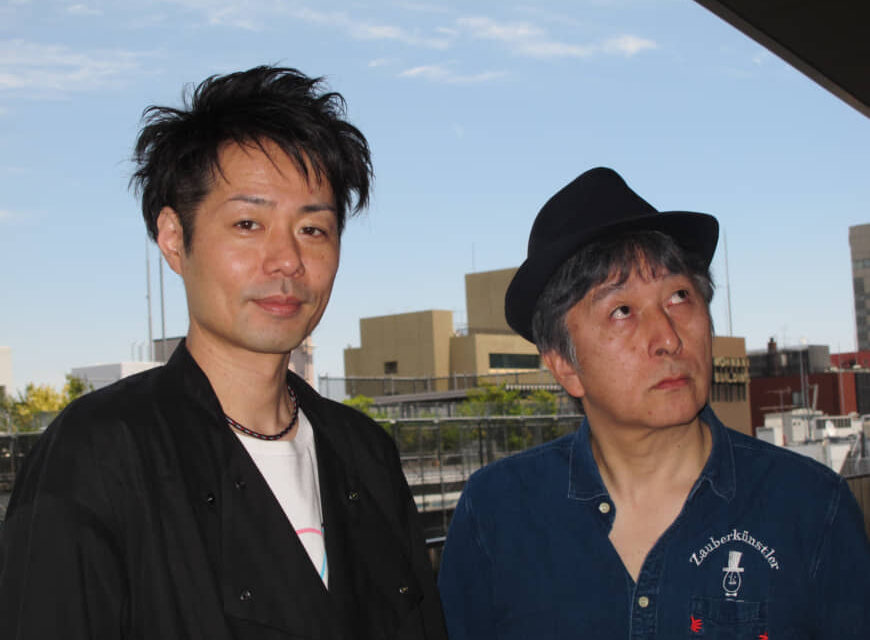

Yet when I meet Tada and Ohtaka — who plays Vladimir — the director is “completely confident” his stagings will yield quite different outcomes.

“With Godot I think Beckett was experimenting with possibilities for dramatical expression that are so different from his novels,” he says. “He presented theater creators with an unreasonable demand to make a compelling production from the simple situation of two men waiting — without having any story development. So this play is Beckett questioning what theater is.”

Tada went on to say that the performance and the way it comes across hinges entirely on the way the actors interpret the lines and in their delivery, given the limited cast and stage setting.

Explaining how he came to be in the limelight this time, Ohtaka says his first brush with Beckett’s play came after he joined a drama club at Waseda University in Tokyo in the late 1970s.

“Back then senior members told me I must read Waiting for Godot before anything else. When I did, all I thought was ‘What’s this? It’s just boring,’” he says with a laugh.

“Those seniors told us newbies to do a two-person improvisation similar to Didi and Gogo every day — and they’d shout: ‘Make us feel emotion and laugh!’ After that, when my friends and I founded the Daisan Butai (Third Stage) company in 1981, we created an original play inspired by Godot.”

That play, Asahi no Yona Yuhi o Tsurete (With a Sunset Like the Morning Sun) — in which Ohtaka played a businessman similar in many ways to Vladimir — was a youth culture hit by the playwright and director Shoji Kokami, and helped propel the company to the forefront of contemporary theater in the 1980s.

“This time I’ve thought again about who Vladimir is and his journey, which I think is very different from Estragon’s,” Ohtaka says. “I’ve also been thinking about other things, such as where is that place represented by just one tree on the stage. I believe this is all a written challenge from Beckett.

“We decided to play it happily because they don’t, or can’t, move from there even if they want to … so we try to enjoy our time as much as possible till the last scene.”

While it may be OK for older people to try and cheerfully accept their mortality, however, how will the young Reiwa team fare in those bleak circumstances?

“The main characters are normally played by veteran actors, so audiences think the two men have already waited for ages and they look quite exhausted,” Tada says. “Also, the standard Japanese translation uses language spoken by older people, whereas I’m using a new translation by Minako Okamuro for both versions, and that’s written in a much more modern, colloquial style with a quicker tempo.”

Besides such artistic considerations, Tada is alert to the social aspect of his parallel plays.

“I personally weigh in my mind what people will feel if they have to wait for a long time from now on — and what they might be waiting for then,” he says. “It’s very interesting, because in the Showa-Heisei version, Didi and Gogo have the confidence to wait because they believe Godot will come one day, so they are optimistic with no reason. But in the Reiwa version — where I try to show a picture of our future state — the young men have their doubts and don’t believe Godot will come, so they are in despair.

“I want to look back to the past, and also imagine the future of our country. That’s my intention in doing these two different generational versions,” Tada adds.

“In the play we repeat the exchange six or seven times when one says ‘Let’s give up,’ then the other says ‘No, we have to wait for Godot,’” Ohtaka says. “Those conversations can be entirely different depending on how you say the lines, so, as Tada says, we voice them with a strong belief that Godot will come one day.”

Tada agrees, saying that he would ask audiences to simply listen to and enjoy the actors’ seemingly silly arguments. “Also, because of the versions’ different social backgrounds, I think they will naturally get different impressions from the same play,” he says.

“I hope people will discover new dimensions to this classic through our productions — and perhaps they might see why Beckett said he’d like to see Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton play these two men.”

Waiting for Godot ran from June 12 to 23 at Kanagawa Arts Theatre in Yokohama. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit www.kaat.jp.

This post was originally published on the Japan Times and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.