Polish theatre artists have recently been experimenting with Virtual Reality (VR). What is it, and how does its use affect the reception of performances?

VR technology is gaining popularity in recent years. It’s used not only in computer games and short films but also in the theatre. Everyone–Skype users, users of GPS navigation or computer games–function in augmented reality, which is where the computer-generated world overlaps with the real one, “extends” it. Usually, however, the recipient can feel the difference between real and second life. The goal of companies working on this technology is to blur this border in order to give the viewer the impression of a strong immersion in the generated world. Then we’re dealing with VR.

Immersion in VR is possible thanks to the 360-degree technique, which allows you to follow the image not only in front of the recipient, but also around it. Sensitive head movements and often eye-catching high-resolution goggles are used for this. When watching a film recorded in this technique, we can rotate around our own axis and follow alternately various frames, selecting ourselves which elements we want to pay more attention to. This creates a sufficiently intense impression of being in the virtual world, so that we forget about its illusory nature.

It’s an increasingly popular technology that is constantly being improved in terms of both quality and availability. However, the goggles through which viewers at the Performing Arts Meeting in Japan were watching Grzegorz Jarzyna’s G.E.N. VR in February 2018 weighed about 800 grams. The question is, how much immersion is possible with such a strong physical distraction?

VR and the power of sight

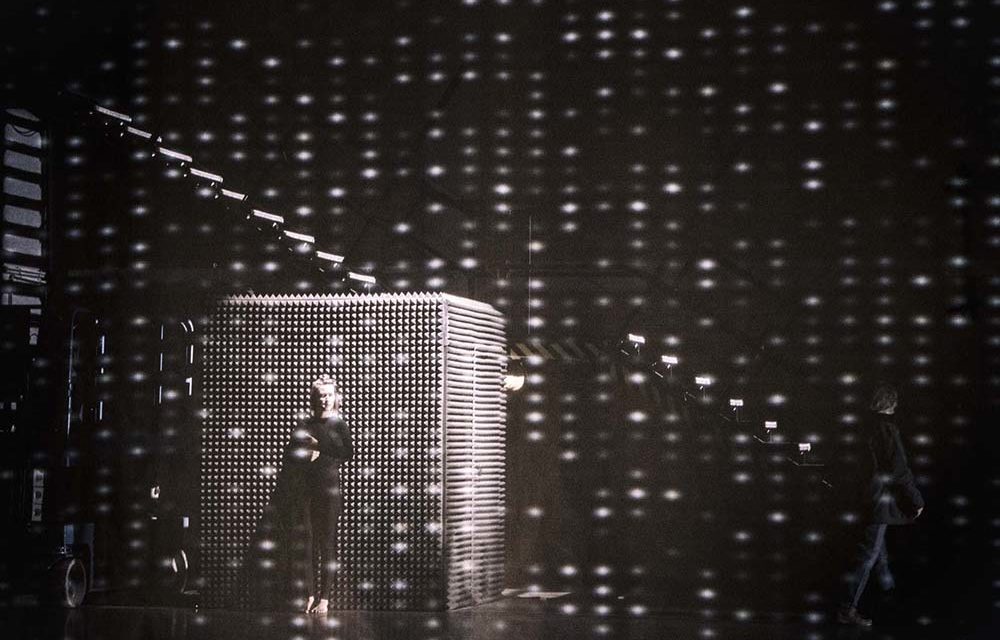

Scene from the performance of G.E.N. directed by Grzegorz Jarzyna; on the photo: Rafał Maćkowiak, photo: Magda Hueckel/TR Warsaw

Mediation, multiplication, image mobility, and editing are nothing new in art, just like the discussion about the relationship between the phenomenon and its image. One of the voices in this discussion was the work of the Russian avant-garde filmmaker Dżigi Stawowa, who considered the camera an extension of the human eye. In one of his manifestoes, “Kinocy. Revolution. With a summons in early 1922,” he wrote:

I – kinooko. I – mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you the world, just as I can see it. Today I am freed from human immobility forever, in a constant movement I get closer to objects and move away from them, I crawl under them and climb on them […]. Here I am, the camera, I am racing after the accident, navigating among the chaos of movements, perpetuating the movement in its most complex systems. […] My path leads to the creation of a new perception of the world.

Wiertow believed that the film recording of an event is equal to the event itself. Whereas in the light of the traditional medium of film, the two-dimensional moving image, it’s easy to reject this idea, in the context of VR technology it’s not so easy. In film, which is subject to classical editing, the director chooses the details on which the viewer’s attention is to focus. In the case of films in VR, the viewer’s eyes have the same ability to select images as in everyday life.

The prospects for this new medium have been appreciated by the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. For Carne Y Arena, Alejandro Iñárritu was awarded a special Oscar, which so far has been awarded only 18 times during the 90-year history of the Academy’s activity. The last film thus distinguished was the first full-length feature film created entirely using computer technology–Toy Story, by Pixar, from 1995.

Carne Y Arena, awarded for its vision and its huge breakthrough in storytelling, is an installation that allows you to experience and trace the fate of refugees at the US–Mexican border from the perspective of their journey. The film was shown at the Cannes Festival, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Fondazione Prada in Milan and the Tlatelolco Cultural Center in Mexico City.

VR in the theatre

Scene from the performance Feast directed by Krzysztof Garbaczewski, 2018, photo: Magda Hueckel/Nowy Teatr in Warsaw

One of the most recognizable Polish theatre directors experimenting with new media is Krzysztof Garbaczewski. Projections in 360-degree technology organize the game space in his performances. In The Feast (premiere: February 8, 2018), VR animations are part of the stage design, corresponding to the stage action, while in Roberta Robura almost the whole spectacle is the visualization of space from the perspective of actors, displayed on a huge screen in the shape of an eye. Similarly, in Platon’s State, Garbaczewski offers viewers a look at the world through the eyes of a character through technology–the actors move in goggles, from which images are broadcast to a large screen.

Grzegorz Jarzyna’s G.E.N. project was the first in Poland VR theatrical realization. Artistic research has been combined with new technology, which seems very adequate in the case of the play on the tension between the individual and the group, which talks about the contestation of social norms. The performance is a response to Lars von Trier’s Idiots (1998), a film about a group of young people pretending to be mentally disabled in order to challenge the norms of Western society. G.E.N. is not a criticism aimed at the social system but rather a diagnosis of the fact that, despite the progress of civilization, people do not necessarily evolve in terms of ethics.

The use of 360-degree technology in the reception of performances has one more important aspect. It indicates new possibilities of documentation and archiving of theatrical works, giving hope for narrowing the gap between an event and its reception.

This article first appeared in Culture.Pl on February 16, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by culture.pl .

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.