A diptych on the re-appearance of other-than-Human movements, with Amanda Piña and Rolando Vázquez.

Choreographer and performer Amanda Piña is steadily building an embodied praxis that aligns itself with the re-emergence of endangered ancestral movements, dance forms and worlds at large. In a context of accelerated extraction of natural resources, plundering of land and life, she is slowly developing a grounded body of subversive work. One of her collaborators, de-colonial thinker Rolando Vázquez acknowledges that, while dancing otherwise, Piña fundamentally unsettles the coloniality of sensing and knowing proper to the fields of performing arts and inspires the imagination of “a world in which many worlds fit.” A diptych about an ever-moving praxis, challenging the colonial boundaries of our very being, revitalizing deeper relations and vibrant cosmologies, breathing life back in the center of our concerns.

J.B.Y.: It would be interesting to start with you. Who is Amanda Piña? What were the transformative moments in your life that brought you where you are now?

A.P.: My father is Mexican, my mother is Chilean. My mother’s grandfather escaped from Lebanon to Chile when he was fourteen. Chile was the end of the world for him. On my father’s side in Mexico, we are said to be converted Jews. So, I already had a war going on inside, even before I was born. During my childhood years, Mexico had no political relations with Chile, which was in the grip of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. My father decided I should be both Mexican and Chilean to be able to travel out of Chile. So, this position of not belonging to one place only constitutes my various identities.

My family was directly affected by the military regime in Chile, as they cracked down and censored a very strong cultural opposition movement. I was born in 1978, five years after the putsch. My memories of these dark times are grey and cold, like winter.

There were a lot of spontaneous demonstrations when I was a child. What I really remember is that we demonstrated, jumping together in the streets against the military regime, while there was huge social movement happening. This form of jumping together, I discovered later, was related to the way the Mapuche, one of the First Nations that still resist in the territory today called Chile, danced in their ritual celebrations. It was my first encounter with dance. This experience of mass bodily movements for justice really marked me. That’s why I have been looking for dance that is not just dance but a social movement, a manifestation of something different, embodied and urgent.

I was aware from early on that there were fundamentally different ways of thinking life. When I was a teenager I had the chance to be with the Mapuche. They didn’t behave like Chileans from the city. They did things differently and had other priorities. They engaged in rituals and talked to entities of the land. I was having this intuition that biological diversity and cultural diversity were disappearing together, but now I know it is difficult for something to really disappear, from the memories of the people, from their bodies, it always comes back in one way or the other.

I moved from Latin-America to Europe, because I really wanted to look for a form of art or dance that would not be about virtuosity, nor about spectacle, but embodied and urgent. As an artist, I found my home in Vienna, a city with a beautiful artistic movement, with a history of political choreography. Today I travel and also present my work in Latin-America, I have a sort of bridging role. Between here and there.

“Like in African dance, you can become the storm or the hurricane, you can be the spirit of the river or the ocean.” Amanda Piña

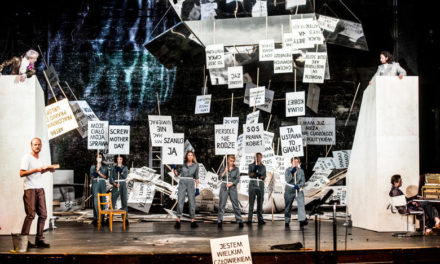

J.B.Y.: Your work was not so politicized from the beginning. Your first work tends to deal with questions of identity and the every day, like in “YOU, “Self” and WE. With Socialmovement/ Theatre Down, would you say that there is a new form of politicization in your work?

A.P. The first performance we did with Nada Productions, which started as a long collaboration with the visual artist Daniel Zimmermann, was called WE, questioning the normative relation with the audience, while we were completely unknown to the scene in Vienna. But it’s true that with Socialmovement/ Theatre Down, I went back to my roots and to the Chilean Issue that was haunting me.

There are works you do not want to but have to make. For instance, Penacho-Ritual, the performance around the restitution of the feather crown from Moctezuma, the leader of the Aztecs. I was invited to do something in the anthropological museum in Vienna, through ImpulsTanz Festival, and as a Latin-American, I could not ignore the colonial history of that place. In Penacho-Ritual we ritually sacrificed the directors of the main museums in Vienna by creating a conversation with a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican spirit that demanded the restitution of the feather crown.

Image of “WE.” Photos courtesy of Nada Productions

J.B.Y.: Can you tell me how this turn came about? With Socialmovement/Theatre Down, you dealt with more political issues, but not yet with the cosmologies of First Peoples. Then with The Dance of Grass, you took that turn and connected with the indigenous struggle. What made you go back to Chile and Mexico, and into the forest rather than the city?

A.P. It was already written in a way. The concept of Endangered Human Movements, indeed came with hindsight, after looking at the performances we had done about coloniality. I call The Dance of Grass, The Camera People, Penacho-Ritual and WAR, Endangered Human Movements: Volume Zero. At the time, coloniality was something I felt and thought but hadn’t read or exchanged a lot about it. It was not the discourse of the moment like it is today. I had a bad time in dance school when I was taught the so-called “history of dance,” which was the history of Western dance, presented as universal. The history, the contemporary … these universal claims are built on coloniality. In Mexico, for example, the contemporary meant to imitate the European and American styles. The contemporary operates as a system of exclusion that favors certain aesthetics, topics, or non-topics and excludes others. I somehow had the obligation in Vienna or in Europe to talk about what is not being talked about, simply because of what I’m made of.

Like in many performances, in WAR, I was really not at ease with the power structures that are at play, so we set to turn the theatre, the museum, the history of dance upside down. Together, with a Polynesian dancer, we created something new out of Polynesian language and traditional Polynesian dances, mixing it with elements of Viennese modern dance. We called it “Manu-inos,” “something strange that came out of the sea” in Rapa Nui. As the performance unfolds, the audience slowly realizes they are just tourists, complicit with armed conflict.

After WAR we started with Four remarks on the history of dance, an archeology of the global history of ethnographic film, depicting the other and their dances. Through this research on the perspective of the camera of white Western anthropologists, we understood that dance could not be reduced to its spectacular or ‘mating’ social function. I was confirmed in my intuition that these dances used to be about something fundamentally different. In Spanish, we have two words for these two different meanings, Danza and Baile, but there is no third word. In Nahuatl though, a language of the Michoacán Aztecs of the high plateau in Mexico, there is the concept of Ixiplatl, that was translated as “representation” by white anthropologists, but it refers more to Michoacán’s enaction or embodiment, addressing “earth beings.”

“The history, the contemporary … these universal claims are built on coloniality. The contemporary operates as a system of exclusion that favors certain aesthetics, topics, or non-topics and excludes other.” Amanda Piña

J.B.Y.: Can you elaborate somewhat more on this absence of a word to describe the third term you are speaking of, a holistic understanding of our surrounding as a being, with ourselves included, this idea of “Earth beings”?

A.P. When understood as Ixiplatl, dance is a form of addressing and establishing reciprocity with earth beings. Earth beings cannot be simply translated as deity. We cannot enclose it in a theological frame, like the “god of the water” or “god of the mountain.” Earth beings refer to the possibility to embody, become and make appear those ecosystems, on different scales, like the mountain, or the jaguar or the people. Through their experience of living on the earth, which we somehow lost in the cities, people used dancing to communicate with these ecosystems through collective forms of embodiment.

The concept of “Earth being” was first coined by Marisol de la Cadena. It emerges from Peru through conversations she had with two Quechua speaking men in Cuzco. The interesting thing of earth being is that you can talk to it, you can reciprocate, and you can become it. Like in African dance, you can become the storm or the hurricane, you can be the spirit of the river or the ocean. The translation of spirit, of course, is problematic because it is transcendental. It’s not only esoteric or spiritual but also very embodied and practical. We are talking about something that can manifest itself here very easily.

Four remarks on the history of dance. Photos by Kat Reynolds

Indigenous people, environmental actors and transnational corporations are talking about three different things when debating on a particular place, like a mountain for example. The transnational corporations are talking about “natural resources” that can be exploited, which is translated into economic assets. The environmentalists are talking about “the environment” in a Western, modern, disembodied tradition of thought. It’s not you. It’s around you, in the landscape. Something bucolic that’s not alive, but inert, irrelevant and somehow also historically feminized. The indigenous people in turn are talking about something quite different. In Nahuatl, for example, you cannot just say “mountain,” you say “my mountain,” like you say “my elbow”. It’s a completely different way of understanding the relationship between yourself, the place you inhabit and the elements that make life possible, like water.

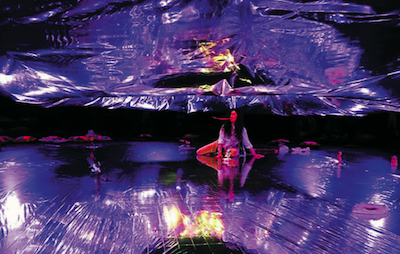

For my new piece Climatic dances we work with the re-emergence of a dance from the Nahua, the Masewal from Sierra Norte de Puebla. In the context of climate change, natural disaster, and accumulation through plundering by transnational mining corporations – “mega-projects of death” as indigenous people in the Sierra call them – some old dances are coming back as they realized they were neglecting their duty to go and dance, bringing offerings to the mountain. The mountain is for them a being, not only geology. It cannot be translated into the matter only. It is a being that gives water, that relates to the wind to create rain. So in this performance, the dancers become the mountain, or the spirit of the mountain.

J.B.Y.: Can you then see the dances you are researching also as a form of technology?

A.P. Totally. I am working with an anthropologist called Alessandro Questa, who told me that dances for the Masewal people can be understood as forms of ancient technology of establishing relations, like 3D-models of socio-ambiental relations. For the native peoples of the Americas, animals, like the jaguar, have been people before. Everything is human inside, with a sense of self and with a human-like consciousness, and not the other way around like in Western thinking, where we have been animals before, but now reached the elevate state of superiority called Humanity. This different way of thinking the other implies that you can establish social relations with that which we call nature.

Matter and energy never get lost, they just transform. Because matter is energy too, in the end. We are just starting to realize this and it is very difficult to imagine. We have been here from the beginning of the world. So, we have been everything in this process. Ancestrality is not a metaphor. If we have been everything, of course we carry with us the memory of all that we have been. Why not think we can embody other beings and communicate with them in other ways than through language?

It’s really about this third space between being and not-being “only one.” All my work really has this idea that we are not “only one.” We cannot be only individual. We carry a lot of beings that allow us to go on living. Other ways of being, being more than one. Being many. Being animal, human, mineral at the same time. The third space, the borderland is really important to understand this. To be able not to have to choose. But to move in between.

J.B.Y.: Through all the intensive relations you built up you seem to be building an important archive. So, in a sense, your work counters processes of extinction and ‘epistemicide,’ and questions about how to keep memory alive.

A.P.: Indeed, but you have to take into account the notion of imperial nostalgia too. People, especially in the West, like to see ruins because they like to see how what they don’t represent is disappearing. But maybe it’s not really disappearing, but re-emerging or transiting or appearing in different, weird places. The dances I am dealing with are now re-appearing in a museum in Mexico and maybe later in a theatre in Vienna. But wherever they re-appear, they do not erase the source. It is not a process of appropriation, but of re-appropriation. It is crucial to honor the sources of this material. But, what we are trying to do is a bit different from “archiving the endangered movements.” The basic movement is to spread out different conceptions of dance, movement and the world, with other principles, different rules of the game, to somehow embody this reemergence.

The School of the Jaguar. Photo by Nada Productions

J.B.Y.: Rolando, in your short text “Precedence, Dance and the Contemporary” on The Jaguar and the Snake you start with a quote by Mara’akame Juan Jose Ramirez during The Jaguar Talks in Tanzquartier Wien in 2019, “The deer is our teacher, our bible, our library.”

R.V.: This opening epigraph from the Wixarika Mara’akame Juan Jose Ramirez juxtaposes the notion of the deer with the text. The animal takes the centrality that the text takes in the West. It expresses a different aesthesis, an understanding of the world that is not textually based, where the animal is not just a companion. It disobeys the human-animal divide. Being and difference are essential for modern/colonial metaphysics, but not for the First Nations of Abya Yala, because the ground of their thinking is relational. In Mesoamerican cultures, there is no “one” nor “difference,” without the relation. The deer then is not an animal, it is not “different” from the human, it becomes an ancestral being that relates to us. In as much as we can relate to the deer, we can enter zones of knowledge and experience that are beyond the logic of textuality.

The question of the oeuvre is inherently linked to this logic of textuality, as it is attached to the author and the text, as well as to the question of being. The canon and the oeuvre work in similar ways. The oeuvre monumentalizes the author. It canonizes or establishes the author’s authority. You might question the mechanisms through which an oeuvre is established as a way of validating the originality, consistency, and novelty of an author. But these are all properties that belong to the logic and power of aesthetics as an order of visibility and recognition. The notion of the author, the notion of oeuvre are there to claim authority and reinforce modern/colonial metaphysics and its ontological claims.

So, when we are speaking of the deer as an ancestor, we raise questions about other possibilities of being in the world. By representing the work of Amanda as an oeuvre, or as authorship, it might erase what is fundamental and most valuable in her work, namely the temporality that she is bringing to dance; which is precisely not the temporality of the author and the oeuvre, but the temporality of precedence, of recovering forms of being on earth that have been erased by the notion of the subject, of remembering endangered human movements.

For Amanda as an artist, it might be strategically important to use these categories of being a choreographer or being the author of an oeuvre. But the de-colonial content of what she is doing is not primarily associated to that understanding of choreography nor to that of the author, as she is enacting the possibility of becoming-animal. Central in this enactment is a notion of animality that precedes us, so we have the possibility of becoming it, precisely because it is before us, meaning that it is appearing in front of us, in space, while also coming from before us, in time. Before the before, so to say.

“De-colonial critique is thus not like self-reflexivity, but like listening to what is beyond our framework of understanding, like receiving what is excluded from that framework. To engage in listening as a mode of critique, it is important to realize your ignorance.” Rolando Vázquez

J.B.Y.: In your reading of her work, you choose to prioritize the sense of listening, or the impossibility to listen to this fundamentally different cosmology. I was wondering why you use the sense of listening in your analysis of the performance. Is this to insist not so much on the sonority of the listening, but on a possible posture of the reception?

R.V.: The modern/colonial order of aesthetics functions through the control of the locus of enunciation. Decolonial aesthetics has to go beyond the primacy of representation, by moving from the aegis of enunciation to the aegis of reception. It is important to ask ourselves what it would mean to engage in an aesthesis of reception, where the horizon is not the individual being, but a process of becoming. When you enter the logic of reception, you can overcome the human subject by receiving and becoming other, not by appropriation or representation. The reception of the other, implies a deep transformation of the self, or even a form of overcoming the self, of overcoming gender and other enclosing differences.

Climate Dances. Photos by Nada Productions

In Amanda’s work, the movement of reception of the other is the reception of the animal in order to overcome the human. Because the animal is not just a companion in the present but an ancestor, it allows the reception of a different temporality that enables our own body to become other. Dance becomes a form and a movement, but a form and a movement sustained by modes of reception, by listening, and remembering that allow it to cross the colonial difference produced in the modern/colonial aesthetic order. It crosses the erasure of other forms of movement that have been silenced. So, listening is about undoing those silences, overcoming the dominant form of representation, the artifice of modernity and exploring modes of listening, modes of reception, that overcome the enclosure of enunciation. The effort of listening then, brings about a different aesthesis, through a bringing to voice, enfleshing what has been erased. It is undoing the colonial difference, the silences that are produced by the control of aesthetics and epistemology.

Listening as a mode of critique can help us to go beyond the modern/colonial order of epistemology and aesthetics. Decolonial critique is thus not like self-reflexivity, but like listening to what is beyond our framework of understanding, like receiving what is excluded from that framework. To engage in listening as a mode of critique, it is important to realize your ignorance. To know that you don’t know is one of the conditions of listening. Humbling the dominant frameworks of epistemology and aesthetics facilitates this capacity of not knowing. The realization of ignorance does not relate to that what is not yet known, in the sense of futurity. That would be the not-knowing of modernity. It relates to a not-knowing that is aware of the bigger erasures around us and to our incapacity to know all that precedes us. This connects to the notion of time and precedence. In modern/colonial epistemologies the past is fixed and monumentalized, whereas the past of not-knowing is the past of an infinite plurality, where the worlds, possibilities and senses that have been erased re-emerge.

“The idea of the author and the oeuvre, is basically the affirmation of the authority of being one. Central in this misunderstanding is the notion of property, ownership that creates the condition of wordlessness, the loss of worlds through eurocentrism and the control of aesthetics.”

Rolando Vázquez

J.B.Y.” So, it is fundamentally opposed to the idea of utopia?

R.V.: Yes, utopia and monumental past belong to the same understanding of temporality. When you speak of precedence, people say that you are conservative or even fundamentalist. We are not fundamentalists, on the contrary. Utopians are attached to a futurity that corresponds to a fixed notion of the past. Our understanding of temporality is never reducible to this logic. The open plurality of what has been lived can never become a monument, it can never be fixed. It can never be appropriated as an object. It can never be just an archive. Time is a radical plurality, the time that has been lived by humans, but also by earth beings, is an infinite plural heritage. When the Wixarika Mara’akame is saying, “The deer is our teacher, our bible, our library” the deer becomes this relation to a deep temporality that carries wisdom and ways of being in the world. We do not invent utopias of the future but work with temporal ethics of hope that responds to the call for justice and for healing of what has been wounded under coloniality.

Dance and Resistance. Photo by Joeri Thiry

J.B.Y.: Can you elaborate on your critique of the idea of oneness, the proposition to be more than one or envisaging the possibility of not being one, as well as on your reference to shamanism as a practice of not being one, being more than one? Does this critique focus on the singularity of subjectivity, more than on the holistic aspect of a certain aesthesis?

R.V. The idea of the author and the oeuvre is basically the affirmation of the authority of being one. The subject is primordial. It produces the sovereign self, but also the author or the conquistador. The position of the sovereign-self is the dominant position in the order of representation, as one singularity it holds the locus of enunciation, the power of representation. You live in the illusion that you are the one that represents, enunciates, that produces you as an author and your body of work as your oeuvre. Central in this misunderstanding is the notion of property, ownership that creates the condition of wordlessness, the loss of worlds through eurocentrism and the control of aesthetics.

Both Maria Lugones and Edouard Glissant speak about not being one, being not one. Also, Fred Moten’s trilogy carries this subtitle ‘consent not to be a single being.’ The question of not being one is about awareness. When moving from representation to reception, we also need to change our conception of owning, as a major relation to the world, to a relation of owing. When moving from owning to owing, you realize you are deeply indebted to human and non-human others. Amanda’s work facilitates a recovery of the body-earth, as a response to earthlessness, to the separation from the earth, but also to the loss of time on the surface of the present. You become aware that your body is earth. The recovery of the body-earth implies also to regain a deep sense of the communal and the ancestral. The recovery of the precedential body means regaining a body that is aware of its provenance and its relation to time, as a response to the loss of time in contemporaneity.

The connection to earth beings in Endangered Human Movements is a way of recovering other movements that I will not call human, but that express an aesthesis and mode of reception that go beyond the human. They bring about a body that is not invested in producing itself as the owner of enunciation, the owner of the world and of earth. They evoke a communal body that is invested in the opening, becoming a place of reception, becoming more than a human, more than a self. They point to an embodiment that exits for a moment the fiction of the self and the binaries it constructs, especially the gender binary.

This article was originally posted at https://e-tcetera.be/ and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Joachim Ben Yakoub.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.