In the middle of the vibrant Berlin district Friedrichshain, well-known for party tourism, hipster cafés, and flea markets, it is possible to find Zwingli Church. The historical venue – with 800 square meters of space, used nowadays mostly as an event location – has been primary sources for the site-specific and site-responsive theatre performance Stimmen des Kiezes by Czech director Petr Manteuffel.

Leader of the independent company StadTheater – operating in Germany but with an international team with Maria Cristina Canta, Anne Diedering, Matthias Hille, Bodil Strutz, Robert Speidel, Bogna Grażyna Jaroslawski, Helena Kontoudakis, Zoran Terzić, and Freya Treutmann – Manteuffel is an expert director. After first experiences in Prague and Hamburg, where Manteuffel trained, the company moved to Kassel and Berlin, where they are involved in conceptual theatre projects for adults, but also working on devised, children’s and youth theatre, such as Jean Cocteau’s A Human Voice, against-together, Charlie Parker is Dead or Robin Hood.

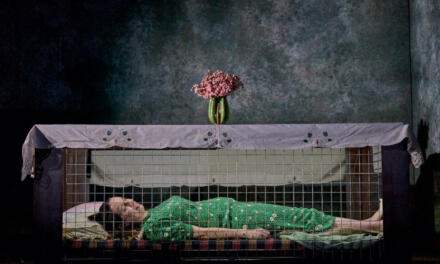

Stimmen des Kiezes has been inspired by the venue itself, from a clear responsive perspective. The main source of inspiration was a painting that shows the drowning St. Peter, whose faith was not strong enough to walk on water, being saved by Jesus. Manteuffel created a collage of text fragments from Shakespeare’s Tempest, Kafka’s The Trial, biblical texts and his own writing, combining the source material with strong visual images, movement, and dance. The performance intended to capture bigger questions of human life in general which created an interesting contrast from the usual expectations of spectators in a church. The very particular set design, created by Bogna Grażyna Jaroslawski, played an important part in this process, using long white curtains hanging in a mystical way from the ceiling and being transformed into various elements such as water plants, animals, walls or boats.

In this way, the venue was necessary to create a text-movement based performance on specific elements of the church itself, where spirituality and Christianity did not form the main part of the context.

Additional value has been given by the musical part, composed by the pianist Zoran Terzić with the insertion of repertoire – such as Monteverdi – performed by the Kammerchor Jeunesse Berlin. A core part of the performance was also Maria Cristina Canta’s solo “dance of the metronome,” a moment that dealt with the meaning of time and interestingly paused the ongoing performance for a while.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Armando Rotondi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.