The First National Veterans Theatre Festival, a partnership between the Feast of Crispian (FoC) and the Milwaukee Repertory Theatre, ran in Wisconsin from May 23 to 26, 2019. Subtitled “Acts of Engagement” and mainly performed by veterans with and without professional acting training, the Festival presented five productions, FoC’s And Comes Safe Home: A Story of Homecoming, The Telling Project’s She Went to War, Mitch Capel and Sonny Kelly’s The Color of Courage: A Two-Man Play with Actors, The Combat Hippies’ Amal, and DE-CRUIT’s Cry Havoc!. Therapeutic processual vehicles for the veterans’ coping with pre-military, war, and post-military traumas (about 20 veterans commit suicide each day in the US), in their public outreach, the performances articulate as activist modalities, mediating theatre as a scene of socio-political interventions. In problematizing moves, they render the design of military power and its internalized structure—the technologies of self/subjectivization prompting soldiers to bind themselves to unit cohesion identity/consciousness—tangible, and so susceptible to subversion.

The Festival opened with FoC’s And Comes Safe Home and closed with DE-CRUIT’s Cry Havoc!. These non-profit organizations employ comparable dramatic and theatrical techniques to safeguard the veterans’ and their families’ mental and social wellbeing. Assisting the veterans’ work with embodied trauma, they rely on mimetic mirroring, the sensory and cognitive coupling with Shakespeare’s characters, whose depictions of war effects evoke, articulate, and afford an address to the veterans’ somatic, psychological, and moral injuries, hence enabling greater connections with others in the world we share. Just as both companies resort to Shakespeare’s inner landscapes to attend to veterans’ emotions and feelings, they also embrace the playwright’s iambic pentameter, its rhythm helping to hold the veterans’ cognitive attention, to check the fragmentary impulses of traumatic embodiment.

In addition to their work with Shakespeare’s characters and meter/verse to re-connect the veterans’ bodies, emotional perceptions, and verbal articulation, they also harness a military structure, Henry V’s “band of brothers,” known today as “unit cohesion.” A powerful tool of military enculturation, unit cohesion incites the soldiers’ vital and committed attachments to one another, to the unit, and to the mission, while desensitizing them to the conduct of violence, and of compassion, towards themselves and the designated enemy as well. In furtherance of veterans’ individual and social reintegration, then, FoC’s and DE-CRUIT’s workshops fashion an emotionally supportive “unit,” a relationally familiar environment through which somatic and psychotherapeutic, affective and cognitive, processing of trauma can take place. Correspondingly, as they retool unit cohesion for civil ends, de-militarizing its warfare affordances, they remake its functionality, ethically revaluing the necropolitical objectives underpinning it.

And Comes Safe Home by The Telling Project. Photo by Kenny Yoo.

The FoC’s And Comes Safe Home gives stage presence to an ensemble of fourteen veterans, one prompter, and a band. Serving in wars from Vietnam to Iraq, in different branches of the US military, and at different ranks, these performers pair their individual and military accounts with apposite excerpts from Henry V, Measure for Measure, Othello, and Hamlet. Doing so, they fashion a series of doubling tableaux, within which the particularity of a personal story is at once concentrated, reflected, and legitimated by the parabolic use of Shakespeare’s scenes. In its therapeutic dimension, the superimposition of the Shakespearean universal over the lived diffuses the veterans’ embodied traumas, validating the soldiers’ experiences as historically shared effects of war. In its social dimension, this doubling focuses the topical issues at stake, intensifying the dilemmas their narratives bespeak.

For instance, how should the theatrical we—soldiers, veterans, citizens—come to terms with bringing wounded, female, enemy civilians to a US military-run hospital, where the staff refused to treat them medically? Here, the theatrical event implicitly conjoins multiplying identities and temporalities, in which the enemy civilians’ lives’ livability then, the veteran’s life then and now, and our lives now are precariously intertwined. Moreover, as the narrative blurs the binary constructed to hold the civilian (the soldiers’ humanitarian impulses) and the military (their rejection by the militarized medical personnel) spheres apart, it also thematizes the line separating them as of an inherently traumatizing ontology. In view of national biopolitics, we cannot but dwell in the necropolitical deadlock of the war situation the soldier-veteran portrays; nor, in light of globalized necropolitics, can we escape the political violence joining us to the “dispensable” life of the enemy civilians. Publicly pronounced and heard, such telling moments of structural—and for the “civilians” often hidden—brutality serve as points of entry for the post-show discussions accompanying each Festival production.

The ethical summoning of and for life’s livability extends to an organizing principle of And Comes Safe Home, a relationality conventionally hidden in liberal theatricality: the prompter-performer rapport. A constitutive part of the mise-en-scène, the prompter, Jordan Watson, is present onstage throughout, lending her voice and touch to those who need it, allowing the “veteran performers with high levels of PTSD and TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury) to feel safe and confident on stage,” as the program says. In the performance’s doing, her work materializes an affirmative social bond, a condition of interdependency, as Judith Butler suggests, constitutive of the very livability of life. Not an invisible auxiliary to the illusionary independent agency of neo/liberal character, the prompter-performer’s interactive rapport is the care to bear up and bear along with, the act by which the performance moves beyond the exclusive representational investment of liberal-humanist ableism. Without this attending relationality, the theatrical present could be not sustained, the historical present not shared, and a more inclusive theatre not imagined.

Mitch Capel and Sonny Kelly’s The Color of Courage comes close to the genre of memorial performance, refining the work of Paul Laurence Dunbar to lend voice and image to “the heroism, dignity, and struggles,” as the program notes, of the African American soldiers serving in the Civil War. Interrelating colonial and military racialization, the performance inscribes and celebrates the African American contributions to the Union victory, problematizing their erasure from the history that still writes the “American people” today.

She Went to War by The Telling Project. Photo by Kenny Yoo.

The Telling Project’s She Went to War unfolds the biostories of four performers, all women veterans. This piece, phrasing the female soldiers’ equal service in combat and conflict zones, disengages the operative biases of the military’s gender exclusion practices, at work despite 2013 rescinding of the Direct Combat Exclusion Rule. Retired Command Sergeant Major Gretchen Evans, who served 27 years in the US Army, conveys what she experienced in Afghanistan when she was, with fifteen soldiers, cut off from the larger task force: pinned down by enemy gunfire on a mountainside, three soldiers dead and three wounded, her group was trapped and running short on ammunition. Here, she explains her leadership practice and what it took to move to the top of the mountain, where they could be evacuated. In parallel performances, Sergeant Jenn Calaway narrates her service in the Marines as a Public Affairs Specialist and Staff Sergeant Racheal Robinson in the Minnesota Army National Guard as a Signal Support System Specialist and in the Minnesota Air National Guard, in Aircraft Maintenance, Nondestructive Inspections.

The explicit portrayal of the equality and respect among the female soldiers and their male counterparts also sounds an implicit critique of the military’s enlistment and enculturation strategies, a reckoning mutually engaged, in one way or another, by all of the Festival’s productions. Inasmuch as recruitment idealizes military service in civilian terms—travel to exotic places, economic security, the acquisition of technical skills, leadership practices, and education—to capitalize on the recruits’ life inexperience (many enlist in high school or soon after) and on pre-military familial difficulties often resulting from economic and political structural inequalities, so, too, military inculcation reinforces the internalization of necessary competencies in ways that render the recruits inherently vulnerable to traumatization. Disclosing how equality of opportunity slips into equality of precarious disposability, Tabitha Nichols, who served in the Army National Guard, reflects on the experience of her wounded body separated from the field tasks it had been trained to perform. In need of medical care, her body-in-pain translates into self-blame, motivating her to reclaim it for soldierly efficiency, justified through a striking discourse that at once evokes and negates Levinasian ethics, the integration of others—those of her unit—into the consciousness of the self, of her professional performance.

Amal by The Combat Hippies. Photo by Kenny Yoo.

The Miami-based Combat Hippies’ Amal, Arabic for hope, is performed by three Puerto Rican veterans, Anthony Torres, Hipólito Arriaga, and Angel R. Rodriguez Sr. This performance is remarkable for the layered and multiplying connections it draws between the historical and the contemporary; the economic, the political, and the social; and between Puerto Rico’s colonial subjection and the military enlistment of Puerto Ricans in the US armed forces. Refusing to trace the state/military sanctioned and hierarchized operational seclusion of veterans from civilians, combatants from non-combatants, citizens from refugees, and national warriors from national enemies, it suggestively reaches to a complex account of radical attachments between differently exploited peoples, such as the “brown” US invaders and the “brown” Arabs they invade.

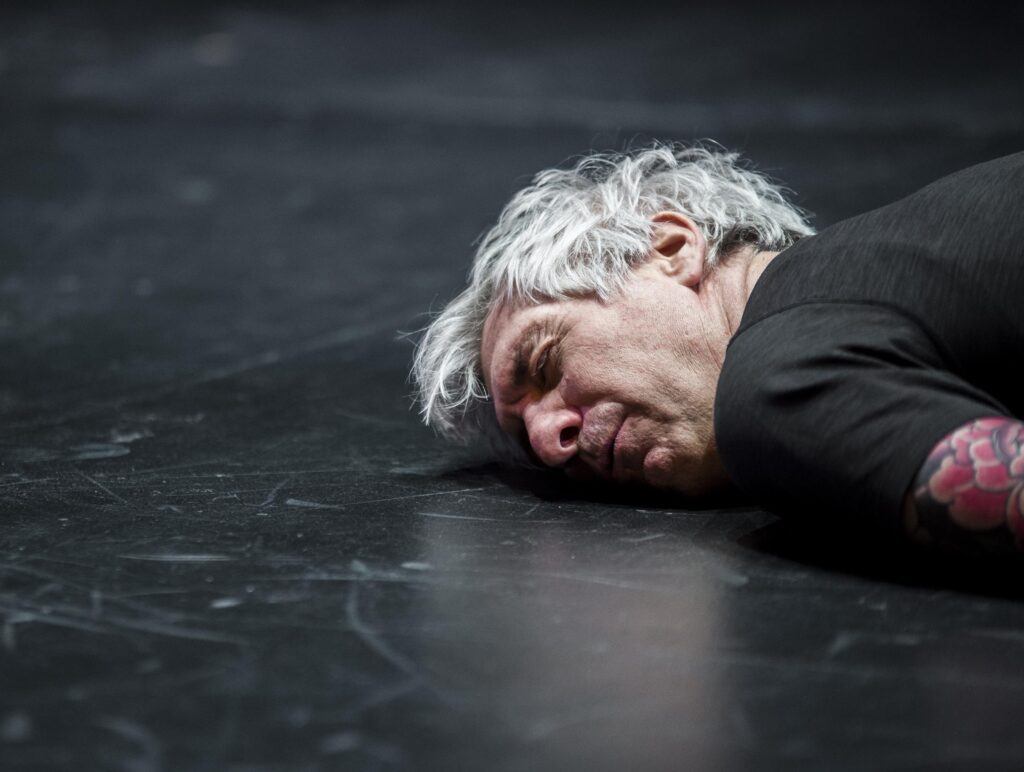

The Festival closed with Cry Havoc!, a tour de force solo, performed and continually developed by Stephan Wolfert, the founder of DE-CRUIT. Intertwining his childhood, adolescent, and military experiences; triangulating Shakespeare’s texts as capacious artistic, therapeutic, and political instruments; and actualizing life as a circumstantial modality formed by the encounters with inanimate and animate forces the body embeds and remembers, the performance contextualizes, critiques, and remakes the processes consequential for the soldiers’ traumatization and the veterans’ re-traumatization, disabling the latter’s social and civic engagement.

De-Cruit: Cry Havoc! by Stephan Wolfert. Photo by Kenny Yoo.

An event of therapeutic, social, and political significance, the First National Veterans Theatre Festival summoned an urgent public gathering in the theatre, creating an environment through which the military territorialization of the soldiers’ bodies and the civilians’ entanglement in it could be, and was, addressed. An event of lived politics, the Festival encouraged an intersectional and interrelated we; a we within which it was impossible to will myself into an independent entity, to find myself free from my pacifism’s other. Motivating us “to see what we see,” to see behind and beyond what blinds us, the Festival does not merely assist the veterans in their control of trauma. It also deploys trauma as a critical means to mediate what Judith Butler in Frames of War calls a “sensate understanding of war, and the conditions for a sensate opposition to war.” Affectively arguing for conceiving life in interdependent terms, for combatants’ and non-combatants’ lives’ livability, for an interrelational mise-en-scène, and for a theatrical experience lived not at the expense of other lives, the Festival arises as a radically democratic act, an act of engagement with.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hana Worthen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.