(c)Giovanni Cittadini Cesi

One of France’s greatest prides is the network of African American artists who, in the mid-twentieth century, came to Paris. Josephine Baker, Beauford Delaney, Ada “Bricktop” Smith, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin. These are just some names of what Paul Gilroy would call a “counterculture of modernity” of the “Black Atlantic” in mid-century France.[i] It is known that these figures found a certain freedom that they couldn’t enjoy back in the US. Racial divisions, the French have a habit of implying, are a problème américain. As just one example, during the 2021 exhibit Beyond Colour: Black and White in the Pinault Collection in Rennes, the section on racism, “Black[s] and White[s]”, was dominated by Frenchmen Raymond Depardon and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs of segregated life in the US.[ii]

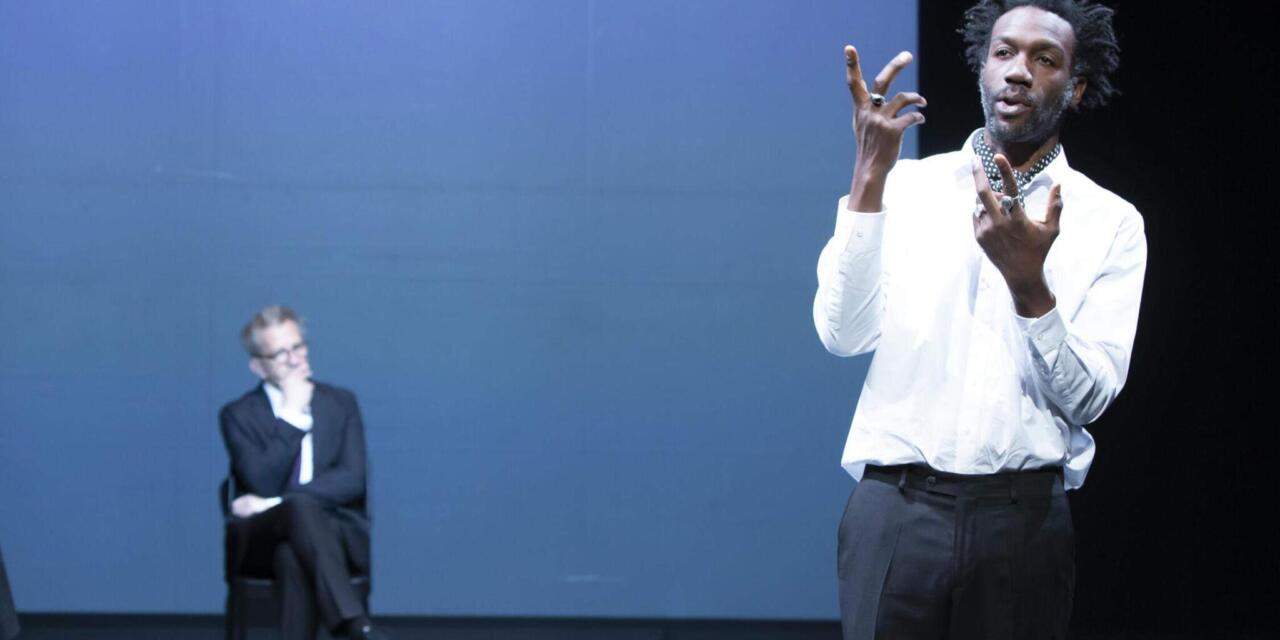

Except, with the rise of the Far Right, with Marine Le Pen dangerously close to being elected in France’s second round of the Presidential elections on April 24, 2022, we cannot pretend that all is well. Portrait Avedon-Baldwin, Entretiens Imaginaires seems all too aware of the timing. Co-created by Élise Vigier and Kevin Keiss, starring Jean-Christophe Folly and Marcial Di Fonzo Bo, the play was originally staged in 2019 for the Comédie de Caen (Normandy). It has been resurrected for a short stint at the Théâtre du Rond Point, Paris, in April 2022. With a focus on the friendship between James Baldwin, prominent member of the Black Atlantic in mid-century France, and photographer Richard Avedon, the show uses mirroring to suggest that the Atlantic Ocean may well be the only thing separating France from the so-called problème américain—and as we know, that oceanic space, as the channel of the slave trade of which France was a participant, is far from neutral.

Mirror, Mirror on the Back Wall

The play stages an imaginary conversation between writer Baldwin and photographer Avedon, two school friends who lost contact and met again in 1963. A year later, they published Nothing Personal, a part-written and part-photographic essay on modern US society, at the height of the Civil Rights struggle and the anti-Vietnam war movement, and a year before the assassination of Malcolm X. As Avedon (Di Fonzo Bo) states, his photographic assemblages across double-page spreads aimed to conjure strange and disquieting juxtapositions; for instance, an ageing White woman, clinging to glamour with deep-colored lipstick versus the youthful Marilyn Monroe, and a Black man staring right at us with glaucoma-beset eyes versus a suited White man of roughly the same age in seeming good health. These figures become uncanny mirrors of one another. The most notable example is the Janus-faced amalgamation of Baldwin and Avedon that the play projects on the back wall, and reproduces in graphic design for its publicity poster.[iii]

Indeed, it is a friendship across borders, built on what unites Baldwin, the Black writer, and Avedon, the White photographer, that is suggested throughout. However, this is not done without acknowledgement of certain differences. The chiaroscuro falling across Avedon’s forehead and jaw almost chromatically commingles with Baldwin’s skin tone in this black-and-white montage, but the play visually and vocally makes the intersectional disparities explicit from the start: Baldwin, Black and gay; Avedon, White, Jewish, and firmly heterosexual. This last category garnered laughter from the audience as humorous acknowledgement of Avedon’s social advantage. We are led to remark the scission in the Avedon-Baldwin photographic montage, the cut which marks where one sitter’s portrait ends and the other’s begins.

(c)Giovanni Cittadini Cesi

There is a complicity to Marcial Di Fonzo Bo and Jean-Christophe Folly’s joint performance that tempt us to believe and emotionally invest in their friendship. The play opens on darkness; all we can hear is their voices in lively conversation as they step into the scene before we see them. Their acting style also mirrors one another’s. Both actors lose themselves in a fast-paced flurry of words as the other listens attentively by his side. A clip of Fred Astaire and a troupe of chorus girls are projected on the back wall; Avedon and Folly insert themselves into the scene, emulating the tap dancers, the diversity of their duo pointing to how white golden-era Hollywood was and, turning to campaigns like #OscarSoWhite, still is.

Against the fractious political climate in France right now—an extreme-right xenophobe versus an unpopular sitting President whose neoliberal globalism has thus far served to line the pockets of the mega-rich—Portrait Avedon-Baldwin instills hope in audience members about the possibilities of alliance across social divides. We laugh as we learn of Avedon’s mother slapping the racist concierge who made Baldwin take the backstairs to the family’s apartment during the men’s youth. Jean-Christophe Folly, as Baldwin, alludes to losing himself when falling head over heels in love, shedding all notion of racial identity—White, Black, or other. The play emphasizes Baldwin’s longing for love as a salvation to the anonymized and splintered society that the US had become by the 1960s, which he wrote about in the written part of Nothing Personal. Rebutting the anti-American joke that it would have been better if Plymouth Rock had landed on the heads of the Pilgrims instead of the latter landing on the rock, Baldwin ends his reflections in this essay with a postdiluvian metaphor: “The sea rises, the light falls, lovers cling to each other, and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the lights go out”.[iv] Eerily prescient of the existential threat posed by climate change, these lines are not quoted in Portrait Avedon-Baldwin, Entretiens imaginaires. However, the sea and its power to unite and divide is present in more ways than one.

Mirrors of Migration

James Baldwin lived in Paris between 1948 and 1957, and finally settled in a quiet maritime Alpine village from 1970 until his death. The play depicts him during an interim period (1963) when he had returned to the United States. The imagined encounter with Avedon makes reference to his Parisian stay, though perhaps not to the same extent as in Baldwin’s essay for Nothing Personal. In the latter, he relates his feelings of security away from American racism: “I have lived in cities where […] it was perfectly possible, and not a matter of taking one’s life in one’s hands, to walk through the park”.[v] Refusing to idealize France in the life of Baldwin, this play does not perpetuate the French habit of exemplifying the African Americans who travelled to France to alleviate domestic guilt about colonialism, as Maya Angelou suggested in the account of her stint in Paris for Porgy and Bess.[vi] Indeed, the play sets up an uncanny mirror not just between Avedon and Baldwin, but also between the actors who play them, Marcial Di Fonzo Bo (“Marcial”) and Jean-Christophe Folly (“Jean-Christophe”), to point to a hierarchy of migration in France.

During the play’s middle-part, the actors recount their own migratory life stories: Marcial is an Argentine immigrant who lived under the dictatorship, and Jean-Christophe, from the twentieth arrondissement of Paris, casts his mind to his Togolese origins. The actors’ life stories blend with those of the characters they play. Marcial alludes to his sister, obsessed with taking family photographs in exactly the same frame (he shows us examples and then affixes them to a flight case that adorns the sparse but sizeable stage). Marcial-as-Richard-Avedon, too, regales us with stories of his sister, whose beauty created such social pressure that it drove her to a psychiatric institution and an early death.[vii]

Jean-Christophe Folly recounts his father’s embarrassment when the actor was obliged to adopt an “Africanized” French accent, for a role in a television film in the early 2000s, which his father knew would only disempower and lead to social opprobrium. This contrasts sharply with the American accent that Folly feigns in humorous fashion at the beginning of the play in his characterization of James Baldwin. The difference between the actor’s reality and that of the historical figure he plays is a reminder that not all foreign accents carry the same privilege. The moment seems to flag up the sinister underside of French idealization of African Americans in France: racism experienced by those from its former colonies.

In other words, what is established is a game of contrasts and opposites between the characters and the actors, who nonetheless have the experience of migration in common. A photographic image of Baldwin (left) standing next to a slightly taller Avedon (right) is projected on the back wall, juxtaposed against Marcial-as-Avedon (left) and a considerably taller Jean-Christophe Folly on the right. These subtle ironies and alienation effects keep us from sentimentalizing the cross-racial friendship. Indeed, certain moments involve us spectators in this hall of uncanny mirrors.

And the Audience…

Members of the public familiar with James Baldwin’s poetic ire may be surprised to find a tempered version of him here. After all, Baldwin, in The Fire Next Time (1963), published one year before Nothing Personal, described his disappointment and rage after the false promises of equal rights for African Americans following their participation in World War II. He tells of a “certain hope [that] died, a certain respect for white Americans [that] faded”.[viii] Portrait Avedon-Baldwin, Entretiens imaginaires makes reference to this book but not the “incredible, abysmal, and really cowardly obtuseness of white liberals” recounted by Baldwin, which drove him to an accept an invitation from black separatist, Elijah Mohammed.[ix] This is not to say that there aren’t more subtle confrontations with the predominantly White liberal audience watching the play.

As Avedon and Baldwin tap dance their existence into the Hollywood frame (mentioned earlier), they also break the fourth wall and enter our space. The moment is brief and doesn’t involve our participation, but both actors engage eye contact with individual audience members, which serves to implicate us in the whitewashed visuals of Fred Astaire and the chorus girls. Jean-Christophe Folly, as Baldwin, makes eye contact with individual audience members, and, I think, harnesses the potential of the actor-audience relationship to communicate Baldwin’s acerbic critique of White culture. Though he did not look at me, when he described, as James Baldwin, his writerly ability to see straight into the heart of people, I felt the intensity of his gaze on the fellow White female audience member adjacent to me. At the end of the play, he laments, again in the role of Baldwin, the disproportionate presence of Black boys in morgues; his statement that he feels the weight of each tragic death of a Black person is extended to an injunction for us to bear this load too. Audience members’ implication is only magnified by the actor’s sustained eye contact.

The show lasts an hour, and we do not see the time pass. The final anecdote is particularly haunting. Avedon tells of his encounter with French filmmaker Jean Renoir in the latter’s California apartment. Amidst the brouhaha of the dinner, Avedon describes to Renoir the disappointment of a missed encounter. Renoir, correcting him, insists that it is not what was said between the two men, but the looks and feelings exchanged that count. The unsaid but most certainly not unfelt. By engaging intense eye contact with us, Avedon’s remarks about being touched by Renoir’s attention to the “stranger/foreigner” (étranger) ring loud and clear as we wait for the final round of the French Presidential election of 2022.

[i] Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard UP, 1993.

[ii] François Pinault is France’s best known billionaire art collector and rival to Louis Vuitton. See: https://www.pinaultcollection.com/en/beyond-colour (accessed 14 April 2022).

[iii] https://www.theatredurondpoint.fr/spectacle/portrait-avedon-baldwin-/ (accessed 14 April 2022)

[iv] James Baldwin, Nothing Personal. Boston: Beacon Press, 2022 [1964], 55.

[v] Ibid., 45-46.

[vi] “The French could entertain the idea of me because they were not immersed in guilt about a mutual history—just as white Americans found it easier to accept Africans, Cubans, or South American Blacks than the Blacks who had lived with them foot to neck for two hundred years.” Maya Angelou, Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas (New York: Random House, 1976), 334.

[vii] Indeed, this explains Avedon’s interest in photographing psychiatric patients, also on display during Beyond Colour: Black and White in the Pinault collection but not in the section dedicated to racial segregation.

[viii] James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time. New York: Vintage, 1993 [1963], 86.

[ix] Ibid., 92.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lara Cox.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.