Lucas Hnath takes a “what if” scenario as the central conceit of his sequel to Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Twenty years after leaving Torvald and her children, Nora returns to the family home to request a divorce from her former husband. Production company Focus have realised two stagings of the piece: one in Madrid directed by Andrés Lima with Aitana Sánchez-Gijón in the role of Nora, the second, a Catalan-language version, now playing at Barcelona’s Teatre Romea directed by Silvia Munt with Emma Vilarasau as an older, assured Nora Helmer returning back to the home she walked out of 20 years earlier. Sánchez-Gijón was a vital presence whose bright blue dress cuts through Torvald’s world once again. Villarasau enters a grey world which her own costume – an elegant Edwardian dress and matching jacket in cream and pale grey – aligns her to. This Nora is now a writer, working under a pseudonym, with short, slicked-back hair, refined heels and the confidence of someone used to operating in the public sphere.

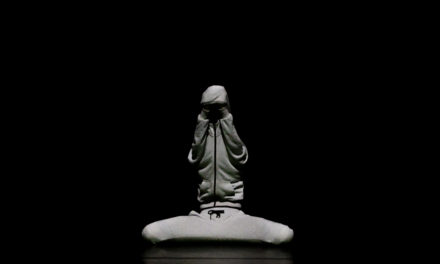

But back in the family home, there is something that unnerves her. Perhaps past memories (both good and bad) that come flooding back, perhaps not knowing who she will encounter or what they will say, perhaps a sense of residing guilt. Enric Planas’ set gives us not the bourgeois drawing room of the naturalistic theatre but rather an empty white space with an open doorway at the back of the stage, two chairs which frame the doorway, and two benches stage left and right. The effect is that of looking at a blank page that has to be filled and fill it Vilarasau’s Nora does, sweeping into the room to try and persuade Anne-Marie, her former nanny, to assist her in her cause: to get Torvald to sign their divorce papers. In a series of scenes – all two-handers – she interacts with Anne-Marie, Torvald and her daughter Emmy as a means of securing the divorce. Nora may be a well-known feminist writer with a following but she still lives in a society where a woman needs some sort of proof of mistreatment or abuse to divorce her husband.

Munt’s production doesn’t quite play out the metatextual levels of the play – Nora is a literary creation who has then provided another literary creation: her own take on walking out on her husband and children. Playfulness is here replaced by a more earnest register. Planas’ set and Mercè Paloma’s palette of grey Edwardian costumes give us a conceptual, abstracted world where the encounters are played out in a direct fashion: each character facing Nora full-on to confront her about her past actions. Isabel Rocatti’s Anne-Marie looks at her in horror when Nora argues for the end of matrimony. Ramon Madaula’s Torvald is visibly shocked when he first sees her. Júlia Truyol’s Emmy, the daughter Nora abandoned, looks at her mother with bemusement. She has a different set of values and a different set of priorities. Recently engaged, she wants marriage and is determined to ensure that the dishonour of her mother walking out on her father doesn’t contaminate her plans.

There is something of a Vilarasau’s Nora that resembles a ghost, floating across the stage in remembrance of things past. She looks around in embarrassment as Ramon Maudala’s Torvald arrives home and she knows she is going to have to face him. Madaula – in a suit that looks too big for him – looks a shrunken presence – always outmanoeuvred by his smarter wife. Nora moves the chairs around as if setting the scene for (and seeking to control) their encounter. She removes her jacket as if stripping down, laying herself bare for their conversation. At times, they break the fourth wall and face the audience in delivering their lines. At times he can barely face her. Torvald’s anger and resentment are palpable.

Rocatti’s Anne-Marie refuses to be co-opted by Nora. She takes the chairs Nora has moved and places them back beside the door. It is as if she doesn’t want Nora to disrupt the family home any further. Nora lies on the bench like a petulant child. Removing her shoes, she is unprepared when her daughter runs in. Truyol’s Emmy captures the uneasiness of facing her mother; she looks gutted when her mother cannot immediately recall anything about her as a child but soon picks up the tconfidence to take control of the situation. The early civilities give way to some more forceful disclosures as Emmy makes clear that she doesn’t want a divorce for her mother but rather her disappearance. As far as she is concerned her mother is dead and needs to remain so. She has a voice here that she lacks in Ibsen’s play and it’s a voice that she is determined to use even if it doesn’t meet with her mother’s approval.

Hnath’s knowing play has a humour that Ibsen’s original lacks. This is a Nora who acknowledges her past in a way that mirrors Hnath’s relationship to Ibsen’s 1879 play. At the end, as Vilarasau takes Torvald’s hand before walking out for a second time, she shows some understanding of the devastating effect the decision she made twenty years earlier had on her family. While I would have liked a more dynamic direction from Munt – the production sometimes feels over schematic with a melancholy violin pointing to a regret that doesn’t overtly feature in Hnath’s writing – Vilarasau makes a fine Nora: moving from the coquettish to the calm and from the nervy to the assured in a split second. The complex emotions that govern her return feel tangible and important. The responses of her family feel legitimate and vital. This is a play where blame cannot be easily attributed, and in an age where insults fly swiftly easily and polarised positions are the order of the day, there’s something to be said for encounters that try to understand the position of the other.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.