The summer season at the Royal Court, London’s premiere new writing venue, features two plays which imaginatively explore the human condition by using elements of the surreal and the dystopian as well as the more mundane and familiar. Or, to put it more accurately, both Alistair McDowall (in All of It) and Tom Fowler (in Hope Has a Happy Meal) show us recognizable human emotions through the lens of highly original storytelling. The overall effect is an exciting contribution to contemporary playwriting — it’s art that seems to make your mind go woo-woo.

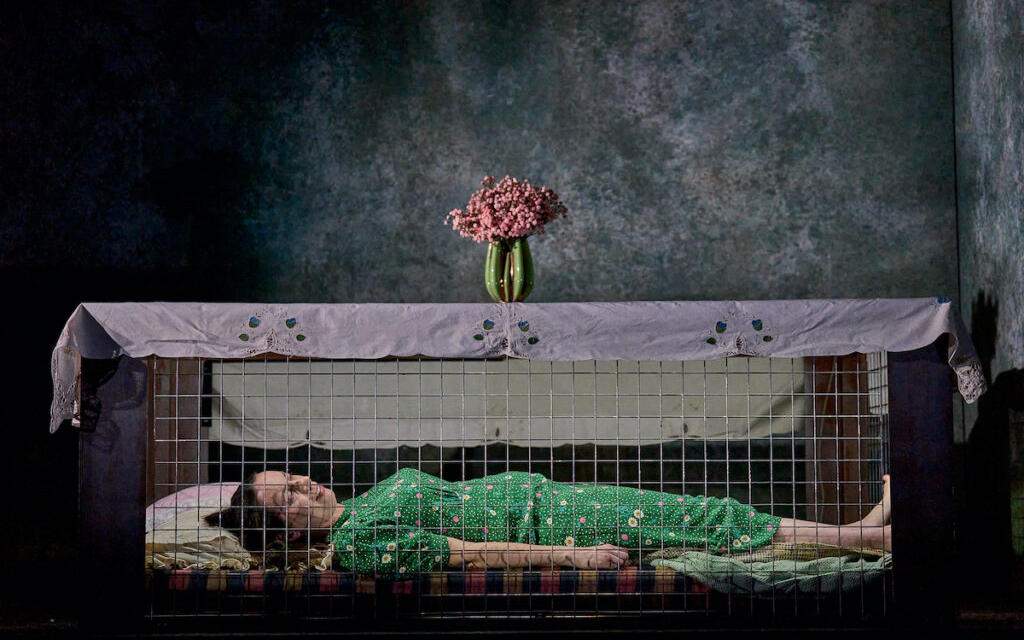

The most mentally explosive experience, in the main Downstairs space, is McDowall’s trilogy of short plays, which are all performed by Kate O’Flynn in what must surely be a career-defining event. Although the overall title is All of It, the first 20-minute-playlet is called Northleigh, 1940. This is about a 29-year-old woman who joins her father in their Morrison shelter, a wire-mesh tomb-like container on the floor of the dining room, during a wartime air raid. Starting with the elevated and inflated tone of lyrical poetry — “Alone, on ashen sands that yearned beyond/ All measure known in realms familiar” — the piece then grounds itself in northern everyday chat, such as “That’s just — Mithering. Bossing about”, as father and daughter make a rare connection.

He has been widowed and the death of his wife, which their daughter says “had no poetry in it” but consisted of “soiled sheets and bowls of thick phlegm marbled with blood”, hangs over them. Naturally, they remember her differently, and he touchingly points out that she never thought the less of him for being disabled, with a damaged leg. They agree that she could be “hard” on both of them. The daughter, fed up with her job as a typist, wants to get married and move out, and enjoys the company of books, especially science fiction and horror stories, more than that of people. Then McDowall evokes the falling German bombs, “fins fixed now in furious descent”, in a passage increasingly and oddly obscure. It’s all intriguing and allusive, but less impressive than the next two monologues.

During the next 20-minute-piece, In Stereo, we watch O’Flynn’s lonely narrator experiencing a psychotic episode in which the actor’s recorded voiceover tells the supernatural story of a damp stain on the wall which gradually takes over her life. Alone on stage in an empty house with only a television, the silent O’Flynn moves warily as her entire life begins to be consumed not only by the growing mould around her, but also by fractures of her self as her words splinter into several simultaneous and competing voices. At first she discovers a doppelgänger in the house and then past and present collide as the streams of words overlap and mix in a kind of Kafkaesque absorption of human and house. It’s fun, but also dark. Very dark.

By the end, McDowall shows how the mottled room, itself a character, will outlive this one woman and will absorb the lives of future generations until climate change washes over everyone. At this point I have to mention the play text. Entitled Three Poems, it is almost twice as large as a regular one and this gives McDowall’s words a lot of room to roam over the page. So In Stereo, especially, has fragments of voices running down the page in narrow parallel lines, and in one glorious playwriting moment are all mashed up in a dark rectangle which is only semi-legible. It’s a thrilling way to represent the inner world of woman and house. As the final words dribble away, the playwright mentions the arrogance of assuming you can squash all of experience into marks on the page. Indeed.

And then he proceeds to do just that when the mixture of Beckettian sparsity with moments of extreme lyricism continues with All of It, a euphoric 45-minute monologue which tells the entire life story of a woman from birth to death. Starting with impressions of birth, then a positively Joycean articulation of baby talk, the piece moves through childhood, puberty, sex, university, love, marriage, pregnancy and divorce. There is adolescent anxiety about her body, the desire to write poetry and a late remarriage. The early death of the speaker’s mother takes its central traumatic place and childbirth is thrilling portrayed as the woman shouts “BABY IS COMING OUT OF ME”. As so often, she imagines — just for a moment — that she’s the only woman to have ever given birth.

Later, the repetitive quality of work is emphasized, and also both the pleasures and pains of family, as the narrator moves from being a teen to having a teen daughter. As a mother she catches herself saying the same things to her own daughter that her mother said to her. Yes, there’s a universal feel to some of these passages. A repeated refrain is “everyone dies”. O’Flynn performs this series of snapshots of the inner life, with its repeats of “I’m fine” (when they are not) and deadening “Driving to work” (for page after page), at a snappy pace which suggests the speed of time passing. It is a life from the vantage point of the deathbed. She is intimate, enthralling, funny, sad and moving.

All of these monologues show how ordinary people have rich internal lives, arguing that each of us have poetic thoughts (occasionally), can be funny in our reactions (sometimes) and are full of fragmented feelings (occasionally). While this is a powerful corrective to the idea that so-called ordinary people are boring and mundane, the sheer imaginative elaboration of McDowall’s writing — with a play text which in all of its poems demonstrates an inventiveness in typography as well as in language — suggests an opposite interpretation: maybe this is just an idealistic aestheticization of normal lives, a kind of retreat from realism. It’s strong, but is it real?

Still, the cumulative effect of the show almost cancels out such carping criticism. Directors Vicky Featherstone (All of It) and Sam Pritchard (the other two), with help from Merle Hensel’s claustrophobic set and Melanie Wilson’s eerie soundscapes, work beautifully with O’Flynn to make this experimental trilogy memorable visually, as well as in its cascades of words, especially parts two and three. It’s the kind of theatre that, as you leave the venue, has heightened all your senses so you seem to experience your own life brighter sharper deeper. You suddenly, for a while at least, feel more alive.

This article appeared on Aleks Sierz on June 8th, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.