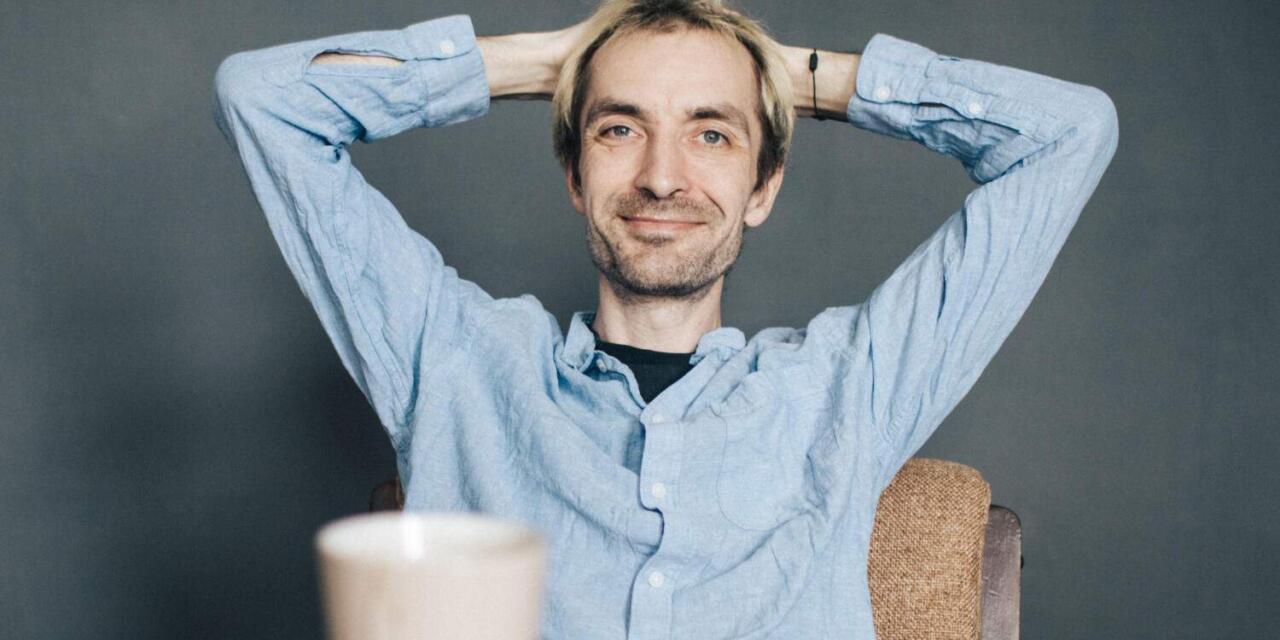

Alexey Strelnicov was a Belarusian theatre critic, director, actor, and tutor. He is considered to be “the engine” of the artisan Belarusian theatre. Alexey appreciated human relationships the most. In his opinion theatre is a place where people are gathering together. Alexey died on December 17, 2022, at the age of 39. His colleagues and friends say that Belarusian theatre has lost a lot without Alexey.

The following interview was made in June 2022 by Hanna Yermakovich for the independent Belarusian media Novy Chas. Alexey asked to postpone the publication: “If I’m imprisoned, publish it immediately”, he said. The original interview was published in Novy Chas on December 18, 2022, in Belarusian.

HY: Alexey, what a war-themed play should look like today?

AS: Until February [2022], it’d have been easier for me to answer. Russia’s attack on Ukraine showed us how the Soviet historical narratives, which were used in conversations about war, have served to justify the aggression. This narrative is still projected from the stage in Belarusian theatres.

It’s not that easy to make a war-themed statement without crossing certain borderlines. For instance, Ales Adamovich’s Khatyn is a worthy book. But at the time of Khatyn writing the Vietnam War was going on, and Adamovich made parallels between the fascists burning villages in Belarus and Americans burning villages in Vietnam. Maybe back then there was a shade of truth, but it’s clear that Adamovich used it to pass the censorship. Ales Adamovich could be shamed for showing the war as not pure heroism, but because in Khatyn he calls American troops “fascists” of the 1970s, it passed censorship.

Badging opponents as “fascist” is a typical propaganda trick. Unfortunately, even the most famous Belarusian plays about WW2 (Privates by Aliaksei Dudarau, Tribunal by Andrei Makayonak), interesting creative texts on their own, are easily integrated into ambiguous narratives. In this respect, when Vasil Bykau’s Alpine Ballad was banned in Ukraine, it was excessive for me. Perhaps, it was an emotional decision for our Ukrainian neighbors, but to critically examine such a text is the right idea.

The point is any artistic statement about war has a presumption of guilt. The author must prove that they consider war critically: the text doesn’t have to be anti-war, and there must be an effort to disassemble the war into components and examine them, asking if the war was unavoidable. Unfortunately, we have only a few such plays and performances.

HY: Have you ever seen in Belarus a play about war that met your criteria?

AS: There were two productions of Nikolay Rudkovski’s Survive till the Premiere at the Belarusian Drama Theatre and at the New Drama Theatre. “The actress” character is rehearsing a play about WW2 and asks herself: “How can it be shown better on stage?” So she tries some absurd things. Thus her question’s presented to the audience. It seems very interesting to me. I should also mention the staging of Zmicier Bartosik’s Master Had a Talking Sparrow. The book emphasizes that “Soviet/German” antagonism is not that significant. There are simply armed and unarmed people.

Today this way to put the question is relevant, because people call each other fascists, but in the end, civilians, who don’t have many arguments to use against guns, are the victims. War crimes are committed everywhere. People who take a specific side are forced to justify the crimes, say, the horrors of Bucha, or the shot knees of Russian prisoners. I believe that there’s a line that shall never be crossed. But it’s hard.

Not so long ago, my troupe staged a play that describes an abstract war between the Roman Empire’s cities. The idea was that during warfare any soldier is initially unfree. The most difficult thing for a person at war is not to turn into a machine. When a commander orders a soldier to shoot a civilian and the soldier obeys, then he stops being a human.

HY: Did you stage this play in Minsk?

AS: Yes. We came up with the following method: while the actors act on stage, the director shouts at them that they are doing everything wrong. Under this constant pressure, the actor shall develop how to disobey the orders. The aim was to discover freedom.

We showed it only once, in a Minsk apartment, on 9 May on purpose. Those who came to watch it thanked us for the opportunity to spend the ambiguous V-Day not hiding from the war topic, but in re-thinking it.

HY: What is the atmosphere of the shows in the state-owned Belarusian theatres?

AS: My colleagues who continue working there emphasize that they aren’t leaving for the sake of their spectators, who still come to them. I saw how in one of the Belarusian theatres, the actors bowed and applauded the audience, which showed everyone both on the stage and in the auditorium was thinking the same. The moments of such a union are extremely valuable. Frankly, it’s what a theatre is supposed to be. But today such cases are an exception.

They say art is the escape from reality. When we see what’s happening behind our windows, we close the curtains and turn on the TV to get switched. Somebody watches a TV show. The other goes to the Opera House, even if they know the staff was fired for their opinions. Somebody comes to Gorky or Yanka Kupala Theatres. I don’t understand a person who comes to the Gorky Theatre, knowing that Alexander Zhdanovich was fired from there. But it would be an exaggeration to say that all these people ignore what’s happening in the country and abroad.

HY: How has the audience of the state theatres changed over the last few years?

AS: I feel like the audiences have shrunk for several reasons. The economic factor and Covid consequences influenced people to visit theatres less. But I’m pleased to think that many Belarusians refuse to visit state theatres due to their political dissent. As for those who still go there, the theatre’s a certain habit of cultural leisure which isn’t easy to give up.

HY: At the very same time the Free Kupalaucy’s audience has grown.

AS: Undoubtedly. I believe that the démarche of the Kupalaucy is the key theatrical event of the Belarusian theatre’s history.

Society has become very politicized. Previously, only 10 to 15 percent of Belarusians had an active political stance, for the rest their maximum participation in the political life of the country was the ritual of coming to polling stations. Now politics is present in the communication with our neighbors. Many of the neighborhood chats are still active. People discuss the most pressing issues. It’s a kind of interest clubs.

This opinion is confirmed by our shows which we present in private apartments. In the summer of 2021, we did a play about the executions by the RSFSR emergency committee during the civil war. Belarusian society has been traumatized by police violence, and it had a hard time accepting this topic, but we’ve developed a specific approach: we presented the harsh text in the most dismissive light way. And people looked at past events and understood: what they are going through today will also pass, someday we will talk about it in the past tense. I saw a Belarusian performance that questioned “What is a family of a police officer?”, “How do the members of this family talk to each other, how do they reason things?” The audience’s response was very active.

HY: Was that a private performance for people you know personally?

AS: Yes, it wasn’t even shown in Minsk.

Obviously, underground shows can’t be mass ones, but each artist makes a choice either to perform for the mass audience or to perform for, say, 20–30 people but speak from one’s heart. I must say that apartment shows aren’t that difficult to organize. Of course, there are risks – we remember how the neighborhood’s yard concerts were cracked down in the autumn of 2020. Yet, I think that the Belarusian security forces’ almightiness is greatly overestimated. It’s impossible to keep a mass phenomenon under control. To intimidate – yes, but to control – no.

Speaking frankly, I’m afraid to do what we’re doing. I don’t want to be jailed, but to submit to this fear means to lose. I continue doing what I want, I am free to choose the material and artistic means. Although this freedom is limited, it is real and very valuable for me.

HY: Do the actors earn anything from the apartments’ shows?

AS: It’s impossible to make a living from. To put the shows on a firm financial footing you need advertising thus leave the underground, which is not the way. Of course, viewers can leave a donation, but this is not what feeds us.

HY: So 28 state Belarusian theatres are just the tip of the theatre life iceberg?

AS: They have always been the tip of the iceberg. There are about 100 people’s theatres in Minsk which are more or less stable independent collectives. I liked one theatre which was run in a high school in Minsk. After the 2020 events, the teacher running it had to quit, and she organized a theatre at her new work in a private school. So creative energy somehow remains, and it’s awesome. [Belarusian] Theatre is now created by those who can’t live without it.

I talked to that teacher. She said that there was some understanding at the level of her colleagues and management. There was the school’s principal who was afraid because he is directly accountable to the authorities. The same situation is in theatres. Actors can think one thing, stage directors – something different, but at the same time, there is a theatre’s headmaster. So the state has levers of pressure on disloyal employees.

HY: Speaking about theatre management, what do you think about people like Vladimir Makei’s wife – Vera Paliakova (who’s been the head of the Young Spectator Theatre since April), being promoted as headmasters of theatres?

AS: I am rather surprised by the fact that quite a few theatre managers kept their positions. It seems that only Eduard Herasimovich said something bloodthirsty about the Belarusian protest participants — God will be his judge. But the vast majority of executive directors have always been selected according to the “if you can manage a bakery, you can manage a theatre” way. People devoted to theatre art are an exception among directors. In this sense, the situation has not changed much.

HY: The mentioned Young Spectator Theatre stages Vasil Bykau’s plays in Russian nowadays. They say it’s for a commercial benefit first and foremost. Is there any benefit to a theatre in such a decision?

AS: When the Young Spectator Theatre stages the shows in Russian, it loses a huge part of its identity. The one and only children-oriented theatre that performs in Belarusian is unique. If someone thinks that performances in Russian will immediately become more popular, they are wrong. Those who didn’t come to see Bykau in Belarusian won’t come to see it in Russian, either. I don’t judge such an approach, but it won’t help the new manager of the theatre to reach their goals.

The value of the Belarusian language has increased so much recently. It’s never been so high, and it should be used. As I understand it, there will be less Belarusian on stage now, because the use of Belarusian will always be associated with anti-government. The authorities will be suspicious of Belarusian-speaking. Belarusian is our national counter-culture.

HY: Do you mean that it’s harmful to go to any of the 28 state theatres in Belarus today, except for maybe the Republican Theatre of Belarusian Drama?

AS: The RTBD and the State Puppet Theatre.

In theory, a group of actors and directors can make a high-quality creative expression that’ll even pass the art council’s censorship in any of the state theatres, even in what is now called “Kupala Theatre”. The problem is that they won’t be able to make this statement publicly, since they can’t rely on the audience to read between the lines. I think such theatricals are pointless. I think it’s not harmful to go to such theatres, it just doesn’t make sense.

Let’s look at the new staging of the Paulinka [the most well-known, classic Belarusian play by Yanka Kupala written in 1912] by the state Yanka Kupala Theatre troupe. There’s a scene, when “Paulinka” shouts to her father that she will stay with “Yakim”. “The father” takes his belt and shouts: “The name of this rebel shall never be called in my house!” They can try to put the play in the ideologically correct way as much as they want, but Kupala already marked the conflict between the archaic world against modernism, freedom, and youth within this play a hundred years ago. The acting of the actor who plays the “father” on stage of the Kupala Theatre is terrible because he has to justify the situation in the country. Ihar Sigau (within the video version by the Free Kupalaucy) plays the same part perfectly, showing the tragedy of a father who realized that he has lost contact with his children. In the state Kupala Theatre’s version, the actor somewhat got hysterical, acting like a domestic abuser. It looked terrible, and it seemed to me that the actor was feeling his lies.

HY: Secondary comedies are forming the regional theatres’ repertoires today. The actors play there without pleasure, for the needs of the easy-going public. Is this format in demand?

AS: We live within a command-administrative system, and theatres’ audiences usually are made of trade union lists. Making an agreement with a professional committee, selling tickets at a discount, and thus filling the auditorium. It’s much more difficult to make a good production and attract the audience. A trade union committee way lets you make a show as bad as you want, and still get the box office. The professional quality of work has little influence on sales now because the state has a theatre monopoly, and the audience does not vote with their wallets anymore. Artists can perform poorly for keeping their jobs if they maintain loyalty. As a result, they lose their skills, and when a really good director comes, it’s difficult for them to work.

The fact that comedies are in great demand in Belarus is a myth of lazy directors who hide their shortcomings with fake statistics. Complex plays of Yauhen Karniah show the great box office despite anything.

HY: What should a young Belarusian who is dreaming of acting do?

AS: It’s a very difficult question. I was shocked to know that at the lectures in the legendary GITIS, the dream of the youth wishing to connect their lives with theatre, Ukrainian literature was named a “fascist” one. I don’t understand how you can study there now even if they have professional stuff. Belarusian universities conduct some kind of classes that used to teach something, but… You see, a truly gifted person doesn’t need this education, and such education definitely won’t help a mediocre person gain skills. The thing is that it’s impossible to get a job in theatres without a diploma. But I don’t see a great need to look for a job in such theatres nowadays. If you can enroll in study programs abroad – try. If there’s nothing to choose from – work with children’s theatre hobby groups. You shall continue looking for independent theatre. I think that’s the way to join a troupe in difficult times.

When we’re talking about theatre education, students need to focus on mastering skills under the supervision of masters whose work they like. I’m sorry for those who have to go to Belarusian schools and universities or go to study in Russia. It’s the worst time.

HY: Is Belarusian culture going through a period of decline or is it some kind of growth?

AS: I shan’t call it growth. Belarusian culture is destroyed. But our time is rich in emotional experiences, and culture is what happens inside one’s soul. I’m sure that there’s no Belarusian who hasn’t faced a difficult choice. What happens now has charged our spiritual state greatly. I believe this charge will be reflected in the cultural field, it’s a question of when and how.

I try to stay optimistic. I don’t want to leave Belarus. I feel that my audience and artists who need me are here. Living in a peaceful, calm country where nobody needs you while staging the tragedies that the people over there don’t understand is not the way out for me.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hanna Yermakovich.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.