The Handke Project, Kosovo Theatre Showcase, Teatri Oda, 26th October 2022

If The Handke Project – written by Kosovo and international playwright Jeton Neziraj and directed by his wife Blerta Neziraj – has a feeling of improvisation derived from its meta-theatre narrative that gives structure to its associative scenes then it is probably deliberate.

Read critical thought about the Austrian author Peter Handke’s work, whom this play is about, and you’ll find some voices who consider his style to be associative, where his episodic writing illustrates internal probings that reflect very personal points of view on life. Handke, who has long been a supporter of Slobodan Milošević (the Yugoslavian and Serbian leader who committed crimes against humanity during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s) and who has accused Bosnian Muslims of staging the Srebrenica genocide, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2019. For those who suffered during Milosevic’s reign of terror, this act by the Swiss committee is unconscionable. For others, it calls into question artistic responsibility and the worry that it will encourage more voices to deny other similar atrocities.

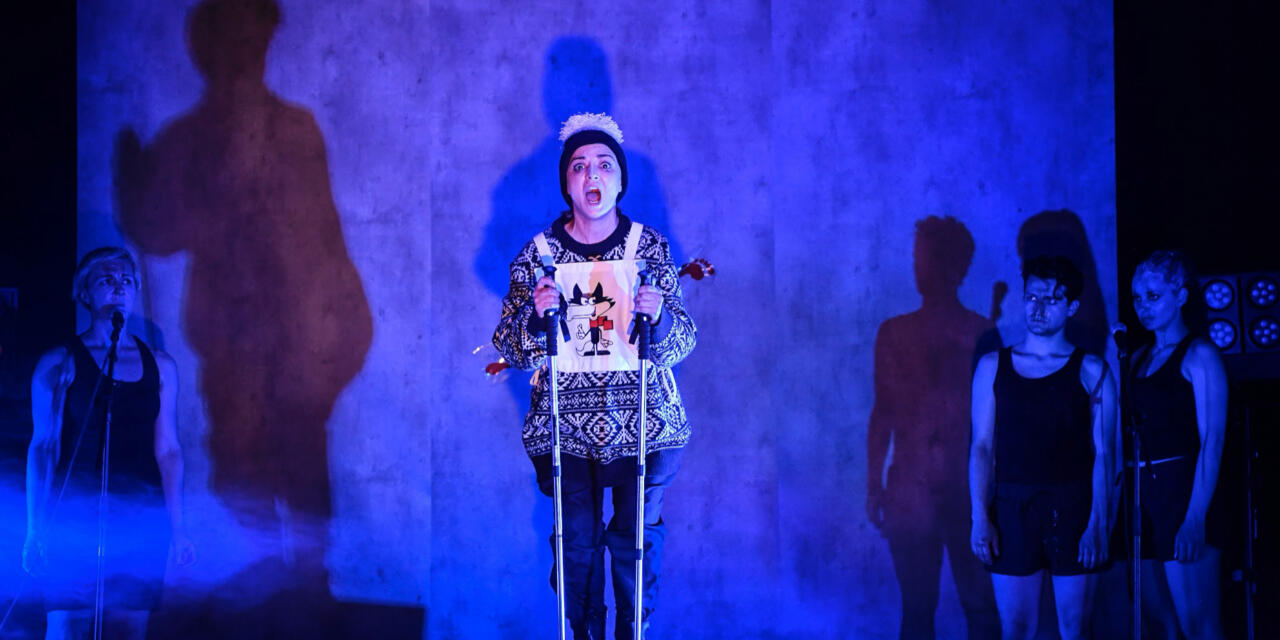

But back to the play. Neziraj strips away Handke’s artistry to reveal the real man beneath. Scenes are taken from his own work and actors take turns playing Handke. A plinth or a monument or a coffin sits center stage and dominates the psychogeography of the space. The actors gather around it, like vultures, to abuse the audience, asking anyone to leave who is fascist, racist etc, in a sly take on Handke’s own “Offending the audience.” The play continues in this meta tradition, with the ensemble discussing and experimenting with different scenes to interrogate and explore Handke’s artistic process.

The play works on several levels. One is where the audience is made aware of the full horror and consequence of Handke’s blind support for Milošević and his denial of one of the worst crimes against humanity since the Holocaust. In an ironic take on art mirroring reality, scenes include a Serbian actress protesting that she finds the material about Handke and Serbia too sensitive (when the company was putting the show together some Serbian actors walked out). These scenes illustrate how Handke’s false views help encourage an aggressive kind of nationalism and a refusal to look at historical truth. Another level explores the ironies and witticisms that Neziraj employs in the text. For example, an onstage “mentor” or “uncle’ figure to Handke is created, with whom he exchanges discussions on writing, a reference to Handke’s writing style where he creates a narrator who is much like himself. These scenes occur early so that the meaning of Handke’s philosophies on writing can gradually accrue, including a sense of how internal and obsessive Handke’s outlook becomes. Then another level tackles artistic responsibility. The narrator disappears and we are left with Handke taking center stage in scenes derived from The Fruit Thief or his Essay on a Mushroom Maniac, placing Handke firmly at the center of his own work. Defenders of Handke have long argued that his abhorrent views on Srebrenica and Milošević have little to do with Handke as an artist – this play is coming down firmly in the camp which sees Handke’s thought experiment about Serbia and Srebrenica as a continuation of his explorations of his fictional work, where only one point of view, his, is the final arbiter of truth. What may true artistic responsibility look like? Here, it takes the form of an ensemble who are working together to try and find artistic and historic truth. Neziraj firmly rejects Handke’s one narrator as the final arbiter of truth in favor of consensus (in the form of the ensemble).

PC: Atdhe Mulla

Lastly and perhaps the most important of all, the play is a monument to human suffering, particularly that of those caught up in the Srebrenica genocide. Blerta Neziraj gives the spotlight to a little boy skiing in the Bosnian mountains whose father is forced by the Serbs to call him down into the village and to his execution. But Handke does not escape scrutiny even here, the scene evokes Handke’s “Repetition” which explores a particular kind of genre writing roughly termed “childhood and landscape” or in German, “Kindschaft.” But Neziraj’s scene is not romantic, but horrific and explores the real consequences of war and Milošević’s reign of terror.

Up until this point, the audience might have felt that they had to go along with the flow of the play, not able to build a cohesive meaning from episodic scenes, a little like how some people describe reading Handke’s own work. But the little boy’s innocence, his childish joy of skiing and the rush of the landscape seen from his perspective and not Handke’s (who at last is no longer centre stage) widens the narrative out, contextualizes it and gives it meaning, depth and humanity. And there is no greater illustration of artistic responsibility than this.

The Handke Project was at the Kosovo Theatre Showcase 26th October at Teatri Oda in Prishtina. It is produced by Qendra Multimedia, in association with Mittelfest & Teatro della Pergola (Italy), Theater Dortmund (Germany), Sarajevo National Theatre and International Theater Festival – Scene MESS (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

It is on tour at:

14-15 November 2022 | National Theatre Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

16-17 December 2022 | Theatre Dortmund (Germany) https://www.theaterdo.de/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Verity Healey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.