The fictional world is our world, but at the same time it’s another place; likewise, the digital world is another place, but at the same time our world. In his latest play, which he performs himself, Martin Crimp investigates and interrogates the writer’s process of creating characters while at the same time exploring the paradox that he himself is Not One of These People, but of course is every one of them too. In this he is aided by his Québécois director and designer Christian Lapointe, who gives the show its digital dimension.

A huge screen on a bare stage shows us images of realistic photos of a huge variety of people, of every age, every ethnicity and every gender, and for each picture Crimp reads a paragraph, or sometimes just a line, of dialogue which evokes their character, personality and attitude. While our imaginations immediately link the image with the dialogue, instinctively sketching in back stories and empathizing with the character’s humanity, it is easy to forget that these images are not real photographs: they are fictional images created by digital technology. Crimp’s invented word-people are represented by invented image-people.

Instead of a plot, or named characters, Crimp has created 299 instances of dialogue, which include the everyday, the familiar, but also the surreal and the mind-bending. The first person says, “I went into that meeting fully expecting to be fired”, and unusually they return later in the show with more details as to why they were indeed let go. Another character has a Japanese girlfriend and is trying to learn her language; another is furious with the way male authors represent women; others are skeptical about communication, or just say that the sky is blue. Still others insist that “I am not one of these people who…”

Crimp’s most provocative gesture is to include statements made by women, gays, black people and trans individuals as a deliberate questioning of a writer’s right to create or represent people from a different identity. He is well aware that young writers today are anxious about which kinds of fictional characters they can invent, and how minority groups might react to such representation. Instead of taking the unhelpful line that any creative artist can invent absolutely anybody, he includes instances which have a challenging side. The audience is okay about laughing at old white males, but the mention of rape or transitioning chills the atmosphere.

This is clearly Crimp at his most questioning, most tentative. But despite their variety, most of these people speak in Crimp’s familiar voice, with its mixture of dry humour, ironic self-awareness and proximity to violence. Like his 1997 masterpiece Attempts on Her Life, there are instances of abuse, prejudice and death. Fraught emotions are pervasive. At the same time, the text has a distinctly new rhythm, occasionally reminiscent in its repetitions to Pinter and in its confessional sections to Forced Entertainment’s 1994 classic Speak Bitterness. In all cases the dialogues are examples of empathy, and maybe occasionally of cultural appropriation.

Although it is organized in 299 sections of dialogue by unnamed characters, the text comprises three distinct moods: the most provocative are the instances of culture wars material, in which our current anxieties about gender and race are articulated in an implicitly critical way. The second recognizable strand is the confessional voices which vary from profound to absurdist, and suggest that we all have something to hide. But by confessing are we revealing ourselves — or just hiding more intelligently? Finally, Crimp explores the role of chance in life with a subtle reference to Oedipus, and other life-changing chance events, some positive and some negative.

The experimental quality of the work — is this a text-based play or an art installation? — goes hand-in-hand with the mild danger of the event. Some passages are prerecorded, others are live, and the possibility of offensive material hovers around the piece although it never crassly intrudes. There are many humorous moments, jokey dialogues, puzzled passages, self-referential asides and both explicit and oblique references to Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka, Greek mythology and Samuel Beckett. In some 100 minutes we explore a fictional portrait of our world, which is weird, wonderful and in its mix of truth and lies, well, theatrical.

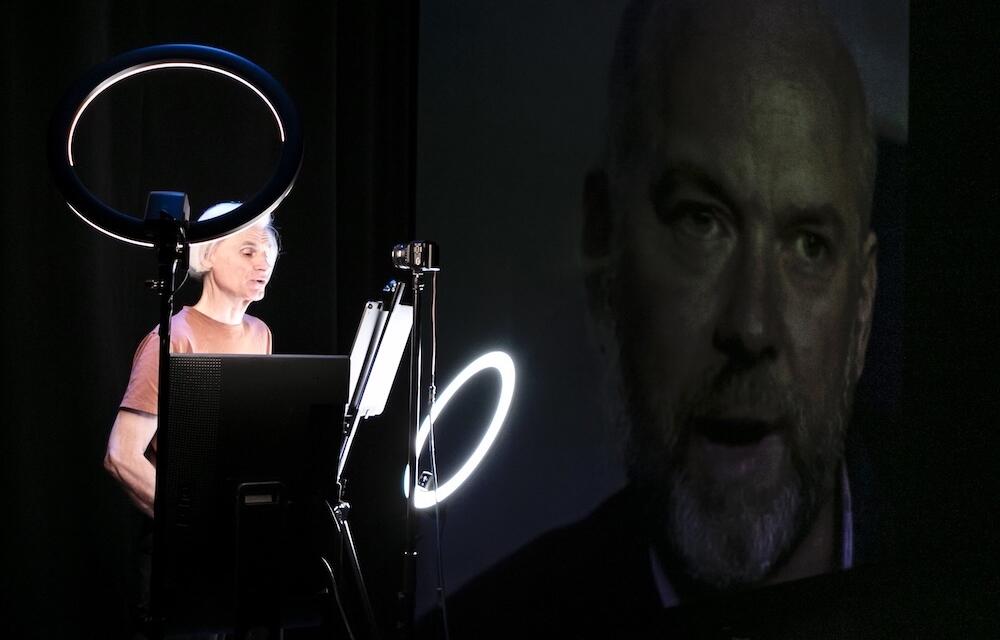

If there are common Crimpian themes — satires on self-help, self-love and self-righteousness — these seemingly random mini-stories are given a lot of drive and coherence in this production by Christian Lapointe, artistic director of Québec City’s Carte Blanche theatre company. At first, Crimp is offstage and our attention is fixed on the faces on the screen, while the playwright’s voice provides the words; when he arrives on stage and takes his place at the side, sipping water and reading from the text, the images begin to move, at first just blinking, and then becoming as expressive as Crimp himself, the images mirroring exactly the facial movements of the playwright. It’s a kind of lip-synch fest.

Guillaume Lévesque, of o/i Hub numérique, has used AI technology to animate still photographs in real time, a process which reminds us both of deep fake tech and of the fact that these images are fictional anyway. There’s something joyous about watching still pictures spring to life, as well as something rather unsettling. When Crimp leaves the stage while his voice and the images continue, it feels like the robots are taking over. Authorial presence turns to absence. Towards the end, the images begin to morph into each other, and Crimp reappears, this time visible behind the screen, working at a writer’s desk.

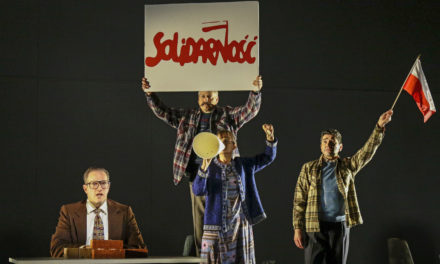

First seen on 1 June in Québec, where Crimp performed it once in English followed on two other occasions by Lapointe in French, Not One of These People is a powerful demonstration of how innovative writing can cross the force-fields of our anxieties about gender, race and consumer society, raising urgent questions about cultural appropriation, artistic freedom and ethical choice (there is a lot about free will and determinism). Clearly, Crimp is not offering any answers, but the theatrical passion with which the show is imbued challenges its audience to think hard about the issues it raises. A rich and rewarding text, which merits further and different productions, it is also, despite a mere four-performance London run, the best new play of the year.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.