Award-winning South Korean playwright and educator Ko Yeon-ok reflects about her teaching practice in a conversation with Kee-Yoon Nahm.

This is Part III of a three-part article. Go back to Part I here and go back to Part II here.

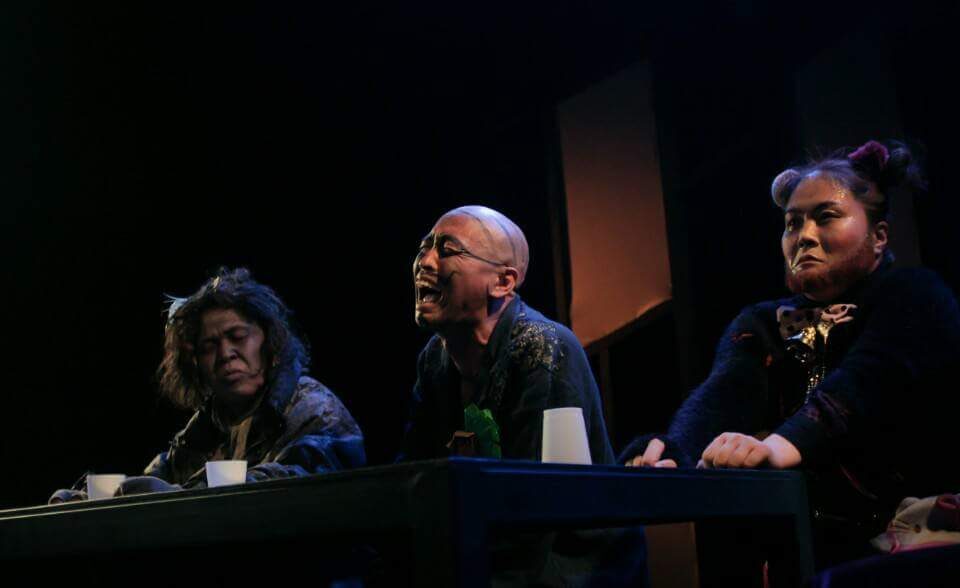

Ko Yeon-ok (Courtesy of the playwright)

Nahm: I’d like to hear your thoughts on the relationship between the playwright and the director. I’ve always felt that there is a dilemma in the title “playwright” itself. As a writer, you have a sense of ownership over your own creation. On the other hand, the theatrical medium requires that you depend on others to realize your work. What audiences encounter is not the text itself, but a staged version of it. Anyway, there can be a lot of conflict in that dynamic. What are your thoughts on this matter?

Ko: When I go to literary award ceremonies that bring together poets, novelists, and critics, I feel like I’m about to suffocate. Other playwrights say the same thing. When writers in other genres create worlds through their writing, it’s as if they are standing on a mountaintop. But with playwrights, our work is only complete when it’s performed by actors on a stage. So plays absolutely need directors, actors, and the stage. It’s a sad thing for one of my plays to exist only as a text. I want my work to become complete through production. And I can’t put into words what I feel when I see my work onstage in an excellent production. Those opportunities don’t come often, so I yearn for them. It’s a tough process—we don’t make a lot of money and communicating with others is hard enough in itself. But in the rare cases where my words shine onstage when the actors raise my story to a sublime level, it’s deeply moving. I can do anything for those moments. I will gladly mop the floor in the rehearsal room, I can buy drinks for the actors and hang out with them. It makes me think that playwrights are more human than writers in other genres. They know how to relate to other people better. The relationship with directors is always difficult. Of course, many directors have deep respect for playwrights. And audiences come to the theatre because they want to experience stories, not just because they are drawn to talented directors and actors. So playwrights have a vital role to play, but, as you know, some directors use writers like tools. In those cases, it’s shameful to be called a writer. Many playwrights are scarred by experiences like that.

Nahm: I don’t know if the situation is similar in other countries, but it seems that there are a lot of directors who are also playwrights in Korean theatre.

Ko: You’re right. But there are even more in Japan. But in Japan, these artists don’t start out as directors. They are playwrights first, and later become directors.

Nahm: In Korea, it seems that many of these playwright-directors are more interested in directing. They like putting their own stories onstage and end up writing their own texts because of that. Sometimes the text feels secondary. What do you think about that trend?

Ko: When a playwright’s text shines on stage, 99.9% of that comes from how much affection the director has for the play. The director has to love the play for the production to excel. So how devoted would a director be if they wrote the play themselves? They work really hard. They push their actors more and rehearse for longer periods. They put a lot of care into it. Objectively speaking, these plays may not be very accomplished as literary works. That doesn’t stop them, though. They keep trying and sometimes they improve. That’s their choice. Speaking for myself, I only want to work with directors who don’t claim to be writers and will stick only to directing. I’ve decided not to work with directors who believe that they can write. As a teacher, when I organize staged readings, I tell writers that they have the capacity to direct their own plays, though directors might think differently. While some directors are quite talented, simple staging is not that hard. So I like to tell my students: anyone can be a director, it’s easy. I say this primarily because playwrights need to learn how to communicate with actors. If playwrights don’t communicate with actors, they get left behind in the production process. There are a lot of theatre productions in which the playwright is alienated. If students get some training in directing, it will be easier for them to communicate with others, especially actors, later in their careers. That’s a good lesson to have. And then there’s another thing. Everyone comments on the play, all the way down to the least experienced person in the team. But people generally don’t say much about what the directing was like, sort of like how it’s difficult to say what’s good or bad about the music in a production. If a playwright can get some directing experience, they have a better sense of what good and bad directing looks like. We talk about that a lot.

Nahm: Could you also talk about problems and difficulties that you face in your teaching?

Ko: To put it bluntly, not all writers are easy to work with. Some are extremely selfish and abrasive. Some have psychological scars and have lived extraordinary lives. There is the danger that they write in order to display or resolve their scars. Some students are consumed by the desire to show off or become famous, all based on a talent for writing. It’s very difficult to communicate with students like that. You have to be strict. They may be hiding it, but it still shows. I try to keep talking to them to connect. But sometimes there comes a point where I’m afraid that I might end up getting hurt by the exchange. That’s where I have to draw the line and stop. There have been five or six cases like that in my teaching career. That’s the most tricky thing. Other than that, I’m happiest when I’m writing plays. Writing plays suits me well and I enjoy teaching it too.

Nahm: You said before that you spend a lot of class time in one-on-one meetings. Do you have some class sessions with all of the students, and others with each individual student separately?

Ko: There are usually two or three students in a playwriting course at K-Arts. But sometimes I have to meet a student one-on-one to discuss their play in more detail. It’s a back and forth between group discussions and in-depth meetings. But one-on-one meetings can be dangerous. I can fall into a trap before I know it. I might start forcing ideas onto students, and the meeting can feel like an interrogation. It’s usually better for a third person to be there, even if it’s another student. It helps if the students can offer ideas and have a conversation on equal terms. So I try to avoid one-on-one meetings when I can.

Nahm: I see. Do you use critical theory in your classes?

Ko: I don’t use theory. When you want people to interpret your play in a certain way, it messes up your writing. You have to write without being conscious of those things, by following ideas in your own mind or excavating from you unconscious. Rather than use theory, I’m interested in merging myth and reality in my plays these days. When I teach, I tell students to find old tales or myths that are similar to the story they’re trying to tell so that they can discover something profound about human nature or the world. It’s worth seeking these connections out. I guess I use Jung’s theories, and Michel Foucault and Hannah Arendt when talking about issues of state power.

Nahm: So you bring theory up when it’s useful, but it’s not necessarily a guiding principle for playwriting.

Ko: Right. In my case, if I’m working on a play based on a myth, I read a lot of philosophy to help me understand it better. These books help me secure a conviction in the issues I want to raise. That kind of research is necessary, so I tell my students to read in that way as well.

Nahm: I see. This is the last question. How long did you say it has been since you started teaching?

Ko: I started teaching at the Playwright’s Institute in 2004, and at universities in 2006.

Nahm: And you’ve continued to write plays at the same time. How has your work as an educator influenced your work as a playwright?

Ko: Working and teaching at the same time is very hard. When I have a deadline, I really force myself to deliver the script in time. But I also have to read students’ work. With these demands, I have no time for myself. As I said before, I’m not just teaching classes. I believe I can only help these students by becoming an example myself. Otherwise, playwriting education turns into an apprenticeship system, forever stuck in a bottle or a mold. I have to continue expanding my horizon of experiences to teach in a way that satisfies me. So I work hard to teach and write at the same time.

Nahm: Is there anything else you’d like to discuss?

Ko: Because the status of the playwright is rather precarious, it’s worth thinking about what aspiring playwrights should be striving towards. A lot of students want to make their literary debut quickly and get their work picked up by places like NTCK. But these days, I can’t help but think that this path can be potentially harmful for young playwrights. If you work towards becoming a famous playwright who has their work produced at large theatres, you can end up writing only to please others before you realize what’s happening. I know some playwrights who did great work in their early careers but went downhill from there. They may have attained fame, but their plays don’t feel alive anymore. I’ve been thinking a lot about this recently. If writing plays is about helping society become a better place, and not just a path to fame, we have to embrace productions in small, less prestigious theatres. Rather than consider productions in these spaces a failure, I mean. You’re not successful just because you’ve worked with a famous director. Working closely with a group of people, even if they’re unknown, can be more valuable. So I try to instill that mindset in my students. Students tend to be drawn to famous teachers and writers, and want to emulate them. I try to shake them out of that illusion. If you start small and enjoy those experiences, you can work your way up to larger projects. But if you take the path to success right away, you can’t go back. These writers are unable to work in small theatres. I think a lot these days about what an early-career playwright’s goals should be.

This interview is part of the project The Global Playwriting Workbook (Methuen Drama 2019), by Ana Candida Carneiro.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.