The word dongpo, a term that refers affectionately to the sizable Korean immigrant community worldwide, literally means of the same womb. This etymology reflects the belief that the Korean diaspora—estimated around 7 million—falls within the imaginary boundaries of Korean peoplehood. Immigrants supposedly still have their roots firmly planted “here,” in Korean soil, even though many of them left the country decades ago, fleeing war or seeking employment, and have seldom visited since.

This emphasis on kinship beyond geography may provide cultural and emotional support for some migrants, but it also creates blind spots. The unique experiences of dongpo lack attention and sympathy, not because these immigrants are no longer considered Korean, but rather because of an underlying assumption that a foreign environment doesn’t change who you really are. As such, immigrant stories in the past have often followed a tired pattern: Koreans abroad struggle to adjust to the new culture and cry longingly for home.

Two new plays break out of that pattern: A Room Without an Air Conditioner, based on the memoirs of Korean-American Peter Hyun, and The Nurses, Who Do Not Return Home, a docudrama about Korean nurses sent to Germany who chose to stay after their contracts ended. Both plays use as their source material actual memories of Korean immigrants who have vexed relationships with their home country. On a larger scale, these plays reveal how unwelcoming—sometimes, openly hostile—South Korea was to some migrants during the Cold War as they traveled beyond the rigid ideological border that the government maintained.

Containing Trauma

Born in Hawai‘i in 1906, Peter Hyun visited the Korean peninsula three times during his life. He was just over a year old the first time, a few years before Korea’s annexation to Imperial Japan. His father Soon, a pastor and English interpreter, joined the interim Korean government in Shanghai and left his children there while he worked in the U.S. to support Korea’s independence movement. Hyun’s sister Alice became a freedom fighter and Communist, later defecting to the North.

His second visit was in 1945, when Hyun (now an Army sergeant) was sent to Korea to work for the U.S. Army Military Government. However, his family’s connections to Leftist figures led to his arrest and expulsion the following year, as ideological turmoil escalated in the peninsula, leading to the Korean War. Hyun was interrogated by the Korean nationalist government during his detention, as well as the House of Un-American Activities Committee after he was sent back to the U.S.

A Room Without an Air Conditioner, produced by Namsan Arts Center and Theatre Company Baeksukwangbu after the play won the prestigious Byucksan Drama Award in 2016, takes place during Hyun’s third and final visit to Korea in 1975. Playwright Young B. Koh chose to dramatize Peter (played by Han Myung-gu) at age 69, when the South Korean government invites him to bury his father’s ashes at the National Cemetery. Despite the great honor, Peter seems disturbed from the outset. Ironically, Peter’s father was being commemorated by Park Chung-hee’s regime, which espoused the same anti-Communist ideology that expelled Peter thirty years ago. As the elderly man with sagging shoulders settles into his stuffy hotel room the evening before the burial service, memories of his painful past emerge.

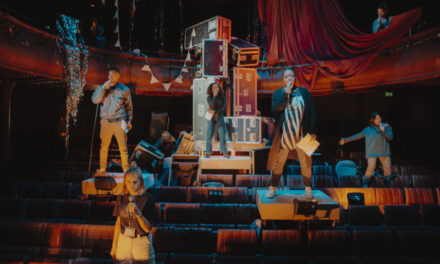

A Room Without an Air Conditioner, written by Young B. Koh, directed by Lee Seong-yeol. Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Baeksukwangbu.

At first, Peter hears faint radio static. He fiddles with the hotel phone and television set, trying to pinpoint the source of the noise to no avail. Gradually, he catches slivers of dialogue between government agents talking about him. He nervously wonders whether the smiling, chatty aide from the Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (Min Byung-wook) is actually an intelligence officer sent to massage information out of him. The production’s outstanding sound design sells Peter’s growing paranoia as the muffled sounds really seem to emanate from the solid surfaces onstage.

These phantasms develop into full-blown hallucinations that also serve as flashbacks. To Peter’s disbelief, a young man (Kim Hyun-joong) suddenly walks out of the closet and begins preparing for a play rehearsal. Peter realizes that he is looking at himself in his twenties, when he led a small theatre company in New York supported by the Federal Theatre Project. The real-life Hyun directed a successful puppet-theatre adaptation of the children’s book Ferdinand the Bull in 1936, only to be voted out of his company right before their next production went to Broadway. He almost made history as the first director on Broadway of Asian heritage, but his white colleagues could not stand taking directions from a “Chop Suey” in public.

A Room Without an Air Conditioner, written by Young B. Koh, directed by Lee Seong-yeol. Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Baeksukwangbu.

This incident, which marked the end of his theatrical career, is lodged deep in the fictional Peter’s psyche like a splinter. It plays out again and again in the solitude of the hotel room. Once he understands that the starry-eyed youth will not go away, Peter confronts his past self, bracing him for the disappointment to come. When young Peter asks about his future as a director, old Peter answers: “I’m sorry.”

As the night deepens, the play makes a flurry of leaps, reverses, and overlaps in time, ceaselessly ripping Peter out of the hotel room in 1975. Director Lee Seong-yeol uses a number of inventive stage transitions to highlight Peter’s psychological disorientation. The back wall of the tight box set recedes the entire length of the stage, transforming the hotel room into a dark cavern. Peter tries to rest in bed. But as the walls vanish, he suddenly finds himself on his knees with his arms bound. An interrogator—a nightmarish version of the Veteran Affairs aide—shouts confusing questions at Peter, although he seems to have already made up his mind that Peter is a Communist agent in disguise. Other people from Peter’s past intrude from all directions, from behind walls, on elevated platforms, through the audience, and most memorably, from an exact replica of the hotel room’s wooden door built horizontally into the stage floor. The stage physically bends and stretches to fit all of Peter’s memories, only to snap back to its everyday form when he clears his mind.

Unfortunately, A Room tries to pack too much history into its contained dramatic setting, especially about Peter’s time in the theatre. This subject was probably too fascinating to leave out, and the emotional confrontation between an optimistic youth and his disillusioned older self does work well. Yet the 1930s plot draws attention away from the more important trigger of Peter’s trauma in 1975: his violent interrogations in Korea and the United States. The play rushes through these chapters in Hyun’s biography so quickly, and relies so heavily on stage effects and frenetic movement, that the Red Scare loses the weight it needs for the “room of memories” premise.

Nevertheless, the play offers a captivating view of modern Korean history from the exile’s position. By the end, I felt relieved that Peter could finally bury his father’s ashes and leave behind a country that caused him so much pain. (The real Hyun lived in Los Angeles until his death in 1993, never to visit Korea again.) A Room asks Korean nationals to learn and sympathize with Peter Hyun’s life, a life undoubtedly shaped by national history, without trying to welcome him “back home.”

To read Part II or this essay, click here.

A Room Without an Air Conditioner, written by Young B. Koh, directed by Lee Seong-yeol. Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Baeksukwangbu.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.