This February, writer Jasminne Mendez’s City Without Altar will receive a staged reading at Stages Repertory Theatre’s second annual Sin Muros Latinx Theatre Festival in Houston, Texas. Mendez has been a fixture of the Houston literary arts scene for well over a decade, marking her collaboration with Sin Muros particularly noteworthy.

After completing high school in San Antonio, Mendez moved to Houston to attend the University of Houston, where she obtained a BA in English and an M.E. in Curriculum and Instruction. Despite being an English major as an undergrad, she stayed connected to her theatre roots, performing in A Raisin in the Sun, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf, and Yerma on the UH mainstage alongside Houston-favorites Bernardo Cubría and Philip Hays. When she wasn’t on stage, she grew into her role as a creative writer, performing poetry in local venues around the Houston area such as Taft Street Coffee House and Avant Garden. In the years since, Mendez has transformed from an emerging talent to a bonafide leader in the Houston arts scene. She is a Canto Mundo Fellow, a VONA Alumni, a Macondo Fellow, and an MFA in Creative writing candidate at the Ranier Writing Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University. Her books include Island of Dreams (Floricanto Press, 2014) and Night Blooming Jasmin(n)e (Arte Publico Press, 2018). Alongside her husband and fellow writer Lupe Mendez, she co-founded Tintero Projects, a literary organization supporting Latinx writers in the Texas Gulf Coast.

In this interview, Mendez discusses City Without Altar, her work as a poet and playwright, the Houston arts scene, and what she hopes to learn about her work during the upcoming Sin Muros Latinx Theatre Festival.

Trevor: Tell us about your new play City Without Altar.

Jasminne: City Without Altar is a choreopoem play about the 1937 Haitian Massacre along the northwestern Dominican/Haitian border. The 1937 Massacre was a government sanctioned genocide during the Trujillo Era. Trujillo believed that Haitians were “contaminating” and “ruining” the Dominican Republic and so he ordered his military men to “remedy the situation” by killing Haitians. Haitians, and even some Dominicans, were massacred using machetes to make it seem like the killings were “feuds” between local farmers for stealing each other’s cattle. The main character Socorro is a scholar who becomes interested in the events of the massacre because she discovers her grandmother’s childhood journal. Socorro is on a mission to learn more about what really happened and she spends her time interviewing survivors (both Haitan and Dominican) about the massacre. Socorro wants to know why and how anti-Haitianism developed on the island, and how/if she or her family are complicit in any way. It’s a play about borders, and language, hate, and trauma, love and joy, reconciliation and rebuilding.

Trevor: What have been the most unexpected aspects of developing this play? What have been the biggest challenges?

Jasminne: The most unexpected aspects of developing this play is the fact that it’s a play! I never intended for this to happen. When I started working on this, I wanted to create a docu-poetic manuscript (docu-poetry is poetry that draws its text and language from archival documents, historical research, interviews etc). I started writing persona poems in the voices of survivors and victims, and suddenly I couldn’t stop. I toyed with the idea of turning the persona poems into a choreopoem play and could see it coming to life on the stage but was nervous about doing it because I’d only written one very short play before. However, once I sat down and started working on it with the lens of a playwright, amazing and fun things started happening. For example, the main character, Socorro, is NOT one of the personas in the original poetry manuscript. Instead, she developed as a necessity to help keep the story moving forward and for dramaturgical purposes.

Even though this play centers on tragedy and trauma, I’ve surprisingly, have had a lot of fun playing with the language, the sequence of events, and challenging myself to keep as much of the poetic language as possible while also trying to make it work theatrically.

I think the biggest challenge has been finding an ending I’m happy with and that makes sense. I think that the play sort of just ends without much transformation or revelation for the main character and I’m still trying to work my way through that. Like what is Socorro’s goal, how does she change, how does this experience change her, how is she or is she not complicit? I think for me, developing the characters more fully beyond their poetic language and short vignettes is something I continue to struggle with. Because I’ve done theatre my whole life, I know what “traditional” theatre is supposed to look and sound like on stage, so I’m constantly worried this play is not enough of that, but then I wonder if it even has to be…*shrugs* I’m also worried about either giving too much historical context or not enough. I’m constantly asking myself “what does the audience need to know” in order for this to make sense?

Trevor: What are you hoping to learn about City Without Altar while working with director Alex Meda at Sin Muros?

Jasminne: Oh man. So. Many. Things. I’ve never really been on this side of the theatrical process (as a playwright). So I’m hoping to learn how to sit still and shut up and let the director do her thing. (LOL) But seriously, I want to know what will and won’t work theatrically with this piece and what edits or revisions I may need to make so that the play continues to move forward. I know that the language in this piece is very vivid, poetic, and evocative. It’s not so much a language and dialogue of action as it is emotion and thought as well as information. It’s a tricky balance trying to infuse historical research and information into a play without boring or losing your audience. I’m hoping Alex can create a space that will highlight both of those elements.

Trevor: You’re primarily known as a poet. Can you tell us more about your shift to playwriting? What can playwriting do for this story in particular that poetry can’t do? Why playwriting? Why now?

Jasminne: Hmm, interesting question because the structure of this play is primarily done with poems and choreopoems I don’t know how much a “shift” this really is. I mean I’ve definitely added some dialogue and have an arc that the original poetry manuscript did not have but I think that what a play can do that a traditional poem cannot perhaps, is 1) the immediacy of the audience interaction and reaction to the language and the story, having that immediate audience feedback and reaction I think is priceless and worthwhile, 2) the whole sense for the scene with lighting, sound, characterization etc I think there’s more emotional intensity with a play than there might be with a poem written on a page and the director and actors can help steer and guide what those audience emotions should be which is quite powerful and 3) I think it really elevates the fact that I’m trying to tell a story in order to bring the human back to a group of “othered” people. In a play you see a physical body saying real words, you don’t have to imagine that, it’s there in your face, in real time and even though these actors are playing a part, I think it can make more of an impact, folks can maybe actually start to feel some real empathy for the “other.”

Why playwriting? Well, I guess I’ve always wanted to do it and theatre is my first love, so why not? Honestly, I’m always looking to try new things and keep my writing fresh and fun. Playwriting seemed inevitable and this just so happened to be the work that ended up being right for the stage. Why now? Well, I think we’re in the midst of a Latinx Literary Renaissance, we are natural born storytellers and I know that theatre speaks to mi gente, a play may be the quickest and most effective way to bring stories to my people, to the people, to any people.

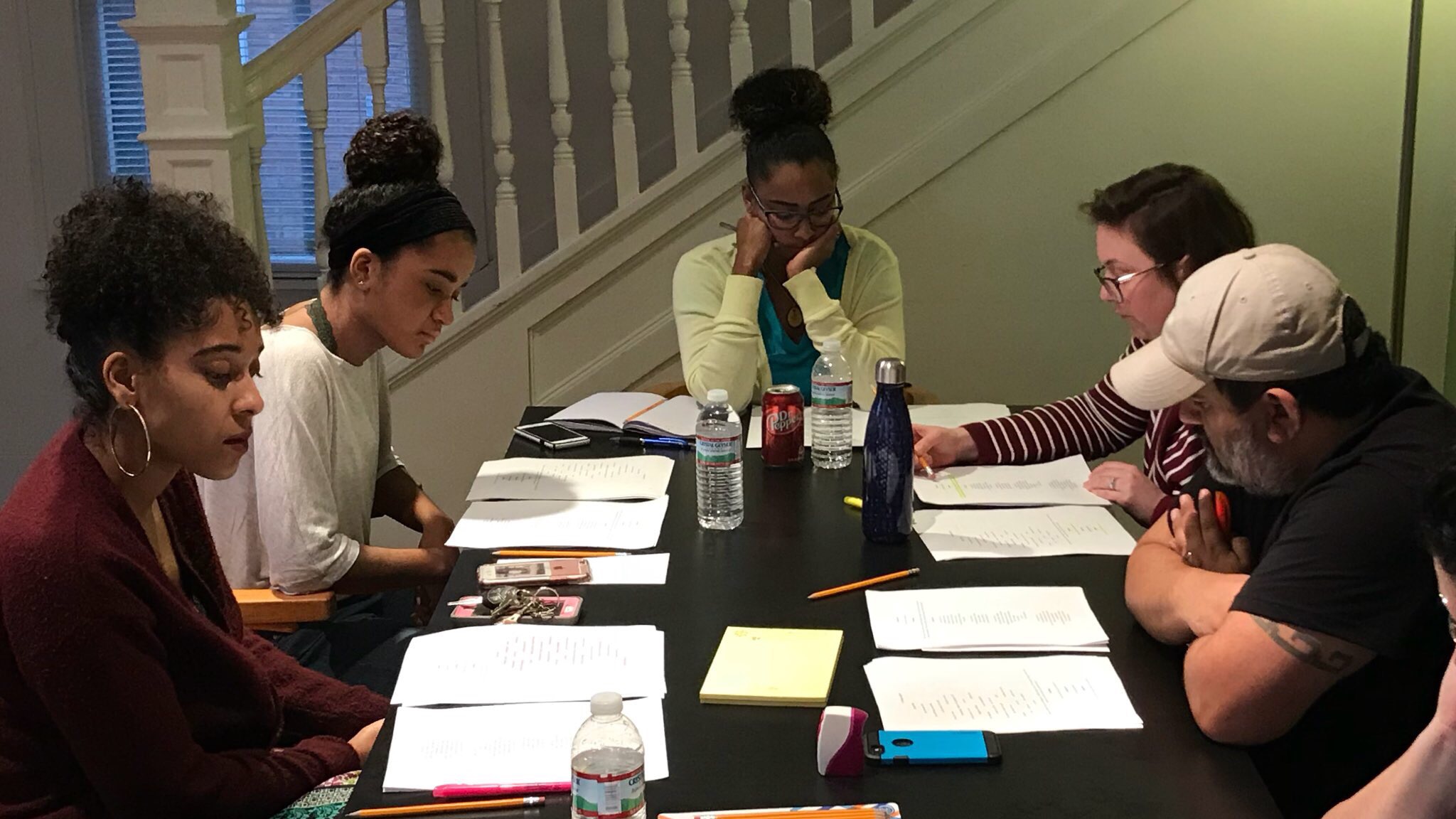

Writer Jasminne Mendez. Photo courtesy of Jasminne Mendez.

Trevor: You’ve been an important voice in Houston’s literary community for well over a decade. Can you tell us more about how Houston’s writing community has influenced your work? Where have you been? Where are you going?

Jasminne: Houston’s literary community has been a part of me for the last 16 years. From reading bad poems at open mics all across town to opening for Sandra Cisneros and winning book prizes, the Houston literary community has always been good to me. While the Latinx literary community is small in this town, we are strong. I’ve made a name for myself because I’m literally the ONLY Afro-Dominican poet in town, at least the only one that gets out there and is doing the work in community. And because of that, though I have sometimes felt tokenized, I have been welcomed with open arms and am always asked to share my work at Latinx literary events. And the way I see it, if someone has to represent Afro-Latinx folks, it may as well be me.

I’ve been just about everywhere in this town, from high schools to community colleges to fancy theatres and museums,from coffee shops to bars and everything in between. My goal is just to keep doing what I do, writing, performing, organizing, rinse and repeat.

Trevor: What else are you working on now?

Jasminne: I’m actually working on finishing up the poetry manuscript version of City Without Altar as part of my graduate school MFA creative thesis. Aside from that, I have a couple of book projects on deck including a YA Memoir on contract with Arte Publico Press, a book of essays on microaggressions as an Afro-Latina in Texas, and working as senior contributing editor for Queen Mob’s Teahouse. Oh, and on top of all of that…just trying to be a decent mom and good role model for my little girl Luz Maria.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Trevor Boffone.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.