There’s a nasty smell in the air. Something rotten. Horrible. I can’t quite put my finger on it. But I’ll try. Something really disgusting, from the dustbin of history, from the past. Or maybe not. Maybe something quite near, but often masked by our ignorance, or our complacency, or our indifference. Anyway, it’s a really ugly scent—the stink of anti-semitism. In the Brexit era, there’s plenty of evidence that racist hate speech is on the increase, and that the digital media have amplified its effects. There has also been a rise in street attacks on Jewish people, as well as on other minorities. And the anti-semitism row in the Labour Party has fuelled a prejudice that many had hoped was no longer current.

In this context, Stephen Laughton’s One Jewish Boy feels really timely, as well as upsetting. The story is relatively simple: Jesse is a young Jewish man, Alex is a young mixed-race woman. In 2004, when both of these Londoners are 20 years old, they first meet at Space in Ibiza. Then, five years later, Alex finds Jesse on a London street after he has been attacked by thugs, and calls an ambulance. Subsequently, the pair fall in love, visit Paris and New York, get married and have a child together. But their four-year relationship is fraught because they can’t agree about issues of personal identity and political belief. And because Jesse is a very difficult guy. Or is he?

Jesse is a bundle of anxiety: after the attack, he’s worried about his personal safety. That’s reasonable enough. But he becomes increasingly obsessed with anti-semitism not only in everyday conversations, about such potentially dangerous issues as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but also in many other aspects of effective life. And his paranoid attitude begins to spoil his relationship with Alex. Although it’s understandable that someone who is the victim of a violent attack by a stranger would feel frightened that it might happen again, Jesse is not really processing the experience in an emotionally healthy way. In his traumatized imagination, he links it with the whole history of the persecution of the Jews, with the blood libel and with the need to cling to cultural rituals such as circumcision.

By contrast, Alex—who has also experienced racism—is much more balanced character. Yet, as she points out, her experiences as a young woman on the streets can be equally tense: you never know when someone might attack you. Still, in general, she has a more easy-going attitude to life, exemplified by the scene in which the couple first meet. In Ibiza, Jesse is chilled and Alex is well off her face. But as they get to know each other more intimately the effects of the assault on Jesse, and his inability to avoid escalating arguments and taking up emotionally fired-up positions, pushes her to her limits. Having a child together only puts an additional strain on them.

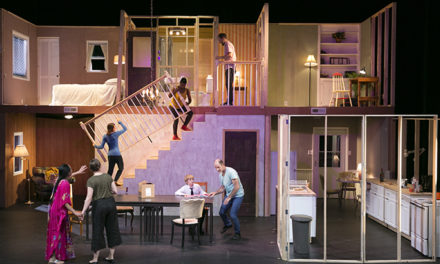

Laughton tells Jesse and Alex’s story using a fractured theatre form, with its 80 minutes of running time punctuated by leaps backwards and forwards in time between 2004, 2009, 2012 and the years up to now. In Sarah Meadows’s engaging and powerful production, this is made clear by the use of highlighted dates on the walls of Georgia de Grey’s colourful set, which features Hannah Lawrence’s graffiti and a claustrophobic screened box that suggests Jesse’s enclosed and fearful mind, with a precarious ledge for balcony scenes that symbolise the couple’s unsteady relationship. Robert Neumark-Jones as the rather callow but increasingly angry and vulnerable Jesse is well matched by Asha Reid’s Alex, who is more grounded, more mature and, in many respects, more appealing character.

But Laughton, whose text has plenty of comedy as well as deep feeling, has chosen to focus on Jesse, and so this is quite a subjective drama. The story is seen mainly through his eyes. For this reason, it’s useless to protest that Alex doesn’t get more lines, or more detail about her experiences of sexual harassment or racist insults: the play is about being Jewish, and what it sharply conveys is the feeling that an accumulation of micro-aggressions and misunderstandings from those close to you can be as hurtful as any assault. This is a piece about experience, not a debate about politics. And its meticulous detail is cumulatively convincing.

If there had been more material about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or about the anti-semitism scandal affecting the Labour Party, One Jewish Boy would have been a different play. Ironically, but perhaps predictably, Laughton has been attacked with vicious anti-semitic comments for writing it. The deluge of hate speech directed at him proves that our much-vaunted tolerant society is actually an illusion. He’s been criticized for not attacking Israel. For not writing about the Palestinians. In response, Laughton, who used to work for Liberal Judaism magazine, has been quoted as saying: “The irony is that the play focuses on the conflating of diaspora Jews with Israeli foreign policy.” And it is this intellectual confusion that leads to some of the prejudice against Jesse, along with more ancient grudges. This drama conveys its points with a powerful mix of passion and intelligence.

This article originally appeared in Aleks Sierz on December 18, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.