King Lear by William Shakespeare. Text adaptation and music scoring by Jan Klata. Translation: Leon Ulrich. Set design, costumes, lighting director: Justyna Łagowska. Music: James Leyland Kirby (The Caretaker).Stage movement: Maćko Prusak. Assistant set designer: Katarzyna Jeznach. Stage manager/prompter/ assistant director: Iwona Gołębiowska. Cast: Krzysztof Zawadzki, Bartosz Bielenia (gościnnie), Roman Gancarczyk, Jacek Romanowski, Jaśmina Polak (gościnnie), Bogdan Brzyski, Mieczysław Grąbka, Radosław Krzyżowski, Jerzy Grałek (image and voice). World premiere: 19 December 2014 at the National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland. Seen in Saint Petersburg during the International Theatre Olympics 2019.

Safety is one of the basic human needs and it was in Russia’s theatrical institutions that people began to truly pay attention to this fact. Hanging up evacuation plans, designating exits from the hall with luminous signs, warning about the rules of conduct in case of emergency; the organizers of The Theatre Olympics 2019 in Saint Petersburg even made spectators safety a priority, which was clearly evident from the information in their festival program. The repertoire here is colourful and includes many famous names and representatives of different schools, beliefs and styles. All of them, however, had been selected in such a way as not to disturb the public, but rather to provide them with pleasure.

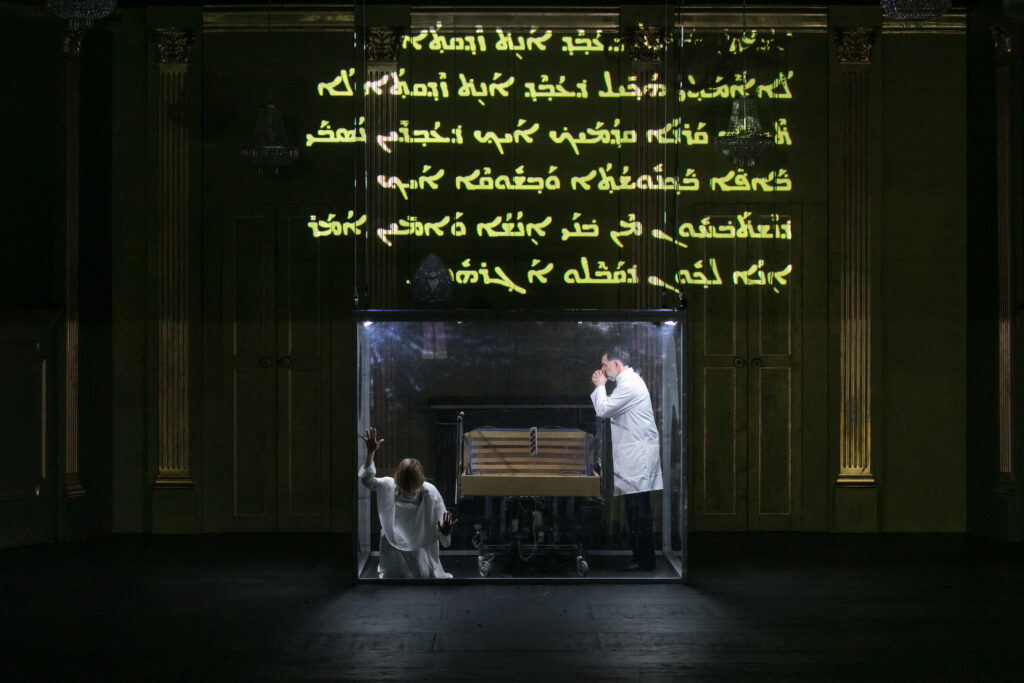

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

Jan Klata, known as a theatrical radical and enfant terrible, appeared before the guests of The Theatre Olympics as a very clear cut, delicate and tactful director. His King Lear was announced as a theatrical provocation involving certain noted attacks on the Catholic Church. In fact, the performance was considered to be a delight for the eyes and a light snack for the mind.

“And is this radicalism?” – the audience, who witnessed attempts to ban the performance of Lear by Konstantin Bogomolov in The State Drama Theatre, Priyut Komedianta were amazed. In this performance, the scene of Shakespeare’s play was transferred to Soviet Russia and supplemented by the texts of Friedrich Nietzsche and Paul Celan. The audience was frightened; the performance Jan Klata put on was a revered event, which left the audience feeling extremely satisfied. For her blood pressure remained normal, her pulse did not increase; her eyes did not get tired because the shelf life of the performance’s radicalism had seemed to expire. The 2014 performance was participated to The Theatre Olympics 2019 and most probably guided by the care of the viewers and heightened safety concerns.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

In Russia, there remains a bitter taste from productions that have caused a wave of indignation and protests related to insulting the faith and feelings of believers. In the days of The Theatre Olympics and the Year of the Theatre in Russia, Member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation, Pavel Pozhigailo took the initiative to close all theatres in Russia.

“The theatre in the full sense is a substitute for the liturgy. It’s a substitution of the Church, ” said the activist.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

It is still unsafe to touch on the topic of religion and in particular, the Russian Orthodox Church, but it is hardly possible to ban anything from the sight of foreign eyes. Moreover, the speech in the performance of Jan Klata is about the Catholic Church. The case of the King Lear play recalls an old Soviet joke from the Era of Stagnation: The American says: “We live in a free country. I can go to the square in front of the White House and shout, “Reagan is a Fool.” And they won’t do anything about it. The Russian replies: “So what? I can also go to Red Square and shout, “Reagan is a Fool.” And for me, too, there will be no repercussions ”

If we ignore the context of the play of the National Old Theatre in Krakow along with the other truly harsh and not indifferent productions of the director, it is worth saying that King Lear is an aesthetic viewing pleasure, for Shakespeare’s play is immersed in the atmosphere of the Vatican in all its beauty and splendor.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

In addition, it is curious that in 2004 Jan Klata staged Vatican Cellars based on the novel by André Gide. Each part of the performance was cinematic and visually verified as being so. Aesthetically, Jan Klata does not oppose church ritual, but instead maximizes its aesthetic wealth. He knows that the magic of red, black and gold pope’s clothes makes a strong impression on the public. In 2014, this was quite an impressive demonstration of this fact because Paolo Sorrentino had not yet introduced The Young Pope. In 2019, it seems to be more relevant and altogether beautiful.

Unfortunately, Jan Klata did not manage to bring the atmosphere with which this performance was played out in Poland, which has caused many difficulties and scandals that in one way or another were connected with Catholic institutions – the scandal surrounding the film The Clergy being a prime example of this; it has all been a very painful process, which has certainly affected the audience’s perception.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

In Russia, the edge of the performance has become dull. The performance does not manage to excite the mind, quite the contrary in fact, for it relaxes the audience and affords them considerable pleasure; everything is well organized, beautiful and pleasing to the eye. Modern technologies such as video projections, modern music like Nothing compares to you by Sinead O’Connor and Smalltown Boy by Bronski Beat, beautiful costumes, choreography, vivid visual images all constitute a highly agreeable evening at the theatre, where formalism is combined with naturalism and ritualistic performance. According to Pozhigailo, here the theatre partially reproduces the liturgy, or – at the very least – appears to be inspired by it.

Church rites are reproduced here and biblical texts are explored and absorbed and yet Jan Klata does not come across as a director that is comfortable transferring the experience of working as a feuilleton player and grave digger to his performances; instead, he proved it by the production of Macbeth in Moscow at the Moscow Art Theatre.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

King Lear conducts a dialogue with the viewer about absolute power, whether it be the power of a god, king or father of a family. In fact, the play is built upon one convincing reception after the director altered certain details of the play. In this updated version, King Lear is the Pope and his daughters are cardinals who fight for power. Here the text of Shakespeare, albeit peppered with directorial narcissism, has been significantly reduced and yet paradoxically, the play does not appear to rapidly develop, rather amble along at rather a leisurely pace that is slightly unbecoming. So whilst this impressive director’s gesture is all in good stead it appears to be repeated many times over through a series of captivating images and excellent choreography.

In February 2016, the performer of the role of Lyra, the master of the Polish scene, Jerzy Gralek passed away. Since that time, the performance has evolved into a new form, although scenes with the participation of Jerzy Grałek are shown in the video. During the performance, digital images are projected onto the backdrop of the scene and various well-positioned screens. An empty throne, an empty hospital bed, a voice from the void all appear to have a powerful effect, which leaves a heavy impression upon both actors and the audience.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Photo by Magda Hueckel from Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019.

In the performance played at The Theatre Olympics 2019, there was no distinct message, anti-clerical manifesto or sense of rebellion. In fact, King Lear turned out to be a literary and musical composition that could be watched with great interest during a special live broadcast on the Internet. In this version – comparable in many ways to a cinematic experience – Shakespeare is nothing more than an occasion for a colorful composition of great balance; a balance that stages the skill of the director. The performance, however, is more like the atmosphere one discovers at a museum, for it is both majestic and pompous whilst managing to remain somewhat disconnected from time. Artistic images are the main event here; the written or rather a spoken word seems dolefully to settle for silver. The hands of the aforementioned cardinals are eloquent and replace whole Shakespearean monologues as they initially join hands in prayer before rubbing them together and plotting intrigue.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

There is neither new reading nor discovery of hidden, encrypted meanings in this version, despite the obvious intertwining of the spiritual and the earthly. It is, however indisputably clear that faith is shown to be false through and obedience a mere screen for sins as each of the heroes fights for power.

The blindness of some turns into a bitter insight for others, and loneliness, madness, old age, death, betrayal, and repentance – whilst all strong categories – seem to be a mere backdrop for the visually spectacular scenes that feature in this performance; formalism here dominates frankness and form conquers emotion.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

The performance is completed by the glass pavilion/cage/cube that has in recent times spread itself across on the worlds’ stages; inside this cube, Lear is locked. The actors of this performance are professional and convincing and create a harmonious ensemble, yet it comes across as though they could all be easily replaced, a little too easily in all earnest.

The performance overall is one such that deserves admiration, but not empathy, for it bears the imprint of another director’s work; works that at one point in time evoked strong emotions in the public that ranged from outrage to protest to praise. This particular director, who likes to say that theatre is a space of confrontation with the audience, offered the audience a most convenient and conformal performance.

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

All in all, this perfect storm of a performance is rather a spectacular show, reminiscent of the final judgment, before which any frail human is both naked and defenseless. Flashes and flickers of light and sharp alongside contrasting transitions replace the original text of the play here and video projections on the scene – shot by the camera from above – symbolize the view of Heaven upon the sinful earth far below, far, far below where unanimous applause sound out across the stalls.

Lear is dead. Long live Lear!

King Lear. Director Jan Klata. National Old Theatre in Krakow, Poland, 2014. Theatre Olympics Press Service 2019. Interpress

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.