Is Sasha Velour a drag queen? It’s debatable. She’s certainly a drag royalty, having won the ninth season of the wildly popular reality show RuPaul’s Drag Race. And she’s certainly a Queen–regal, dramatic, authoritative, demanding of our attention. But if the basic definition of drag is a spectacular reimagining of the opposite sex, well, that’s not what Velour does. For Velour, the idea that there are only two sexes, diametrically opposed, is ridiculously reductive. In her show Smoke & Mirrors, Velour, who is gender fluid and uses feminine pronouns when dressed as a Queen, pushes us to realize that the distinction between male and female, like past and present, good and evil, singular and plural, is a construct, restrictive for daily living but productive for artistic creation.

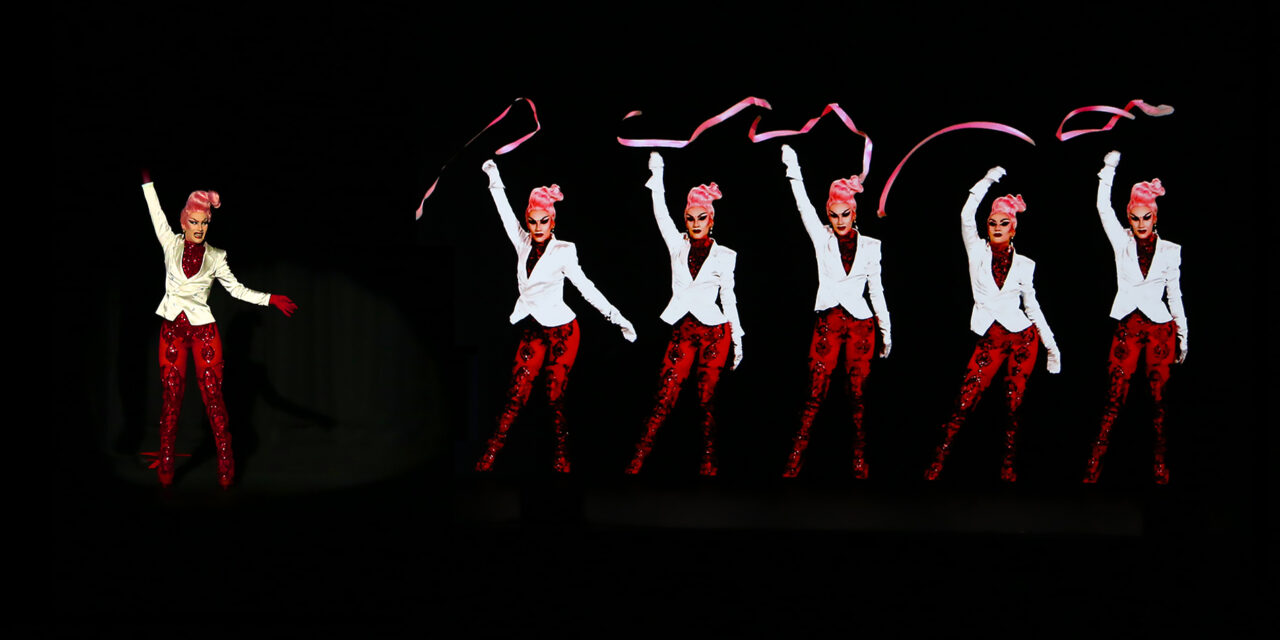

Sasha Velour, beyond good and evil. Photo courtesy of ITD Events/House of Velour.

Smoke & Mirrors, at New York Live Arts, consists of thirteen lip-sync performances, including some drag standbys like Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand, plus poppy entries by the likes of Le Tigre. We’re treated to Velour’s career-making performance of Whitney Houston’s So Emotional, the number with which she clinched her season of Drag Race. In between, we get stories from Velour’s life and career–her entrée into drag from the starting point of being “the gayest person” in a small town in Vermont, the loss of her mother in 2015. Judy Garland referred to her momentous 1951 concert at the Palladium in London as an autobiography in song. Velour’s show is nothing less.

This is Velour’s first one-person show, although she also hosted the Brooklyn-born drag cabaret night Nightgowns. And yet, it’s not quite right to say that there’s just one person in the show. There are many performers and characters, but most of them are Velour herself. Velour is also an accomplished visual artist, and she combines video art, animation and light projections to crowd the stage with versions of herself. The show opens with a performance of Cellophane by Sia. Velour stands alone onstage in a giant white smock-like gown, onto which an image of her own singing face is projected. Behind her, vibrant colors spread in shades and lines evoking, at least for this old millennial, Microsoft Paint. That’s two Velours. For Lana Del Rey’s High by the Beach, the magician Velour cuts the lovely assistant Velour in half. That’s three Velours–the torso and the legs in the magic trick traditionally (that is, required by physics and human society) performed by two different people.

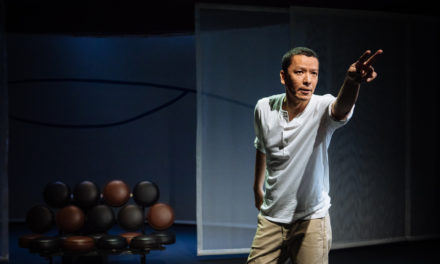

Photo courtesy of ITD Events/House of Velour

My favorite performance was the Annie Lennox song Keep Young And Beautiful, which featured an indeterminate number of Velours. Three figures in ruffled silky costumes of violet, magenta, and turquoise perform a sprightly dance while wearing masks of Sasha’s face. The masks are removed to reveal monstrous representations of Velour’s signature exaggerations–sharp fangs, Nosferatu ears, unkempt eyebrows. The costumes, as throughout the show, tell the story, but in this number, the performer wearing them is another Velour, Johnny, Sasha’s partner.

On the other end of the spectrum is I’m Alive by Celine Dion, which is literally and figuratively stripped down. A shadowy, black-and-white projection of Velour shows her undressing, undressed and dressed back up, to the nines or maybe the elevens. Velour often performs bald, in Smoke & Mirrors her head is spray-painted hot, hot pink, but she uses astonishing sculptural wigs as accessories. In I’m Alive, she takes off her wig and gown, revealing the tight corset she wears to achieve her look, but she doesn’t stay bare for long. She spritzes herself with Chanel No. 5, and begins the transformation all over again. Like Wig In A Box from Hedwig, the staging of this number addresses the hard work, physical, emotional, and creative, it takes to become the best you’ve ever seen.

Sasha Velour is a cerebral queen. She’s the founder and artistic director of the gorgeous publication Velour, The Drag Magazine, now out in trade paperback and available for purchase in the lobby of Live Arts during performances. Velour has a literature degree from Vassar and happens to be Russian academic royalty. Her father is the historian Mark Steinberg whose History Of Russia is a cornerstone for kids who major in Russian Studies in college, such as the author of this review, and her late mother Jane Hedges was the managing editor of Slavic Review. Gender roles are traditionally strict in Russian society, but it’s not immune to drag; check out Jennifer Wilson’s article (Drag)ging Tolstoy Into Queer Theory: On The Cross-Dressing Motif In “War and Peace.” There’s no tradition so solid that it can’t withstand a little gender-bending and, I would argue, the ones that let it in regularly, via Carnival, Halloween, or Purim, have a better rate of survival. Velour’s costumes and design can’t be explained through conventional narrative, but they make intuitive sense like another Russian artform, neologistic poetry called zaum or beyond-sense. Velour is a genre unto herself, but if there’s another Queen she resembles, I guess it’s Catherine the Great.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.