There is one wonderful detail in the Russian language. The letter E (“ye”) can be absolutely equivalently read as the letter Ё (“yo”). But not vice versa. Often, people are just too lazy to put two dots over the letter E, they are just in a hurry . . . but everyone (vse) understands everything (vsё), right? See? Sometimes this small feature can change the word, making it deeper, more global and meaningful.

The play by Dmitry Krymov is called Everyone Is Here. It is these words that form a refrain in the final scene at the cemetery in Our Town: “Everyone is here . . . Everyone is here . . . Everyone is here . . .”

Of course, we are talking about people buried in this cemetery, among whom, mixed with the heroes of Wilder’s play, are Georgian artists, mom and dad, grandparents, and Nonna Mikhailovna. They balance in the finale on a shaky platform, on the edge of an imaginary abyss. They are still here, although their position is unsteady, and it seems that they are about to fall together in unison, and there will be no one else, no one left.

But for now, they’re still here. Everyone is here.

Need to decipher anything to answer the sacramental, annoying question of newspaper journalists, “Why did you decide to name your production like that?” Because everyone is here. Everyone is in the cemetery.

And everything would be obvious and simple if not for that damned Schrödinger of the letter E. Which at the same time can be read as a phantom “Yo.”

The thing is that this amazing performance is not so much about the people who appear in it, not about personalities, but about the memory of ONE person who keeps in himself like in a huge mass grave the images, emotions, moods, fragments of completed and failed performances, smiles and tears, pictures and toys, and of course people.

It’s all inside his head. In his memory.

EVERYONE IS HERE.

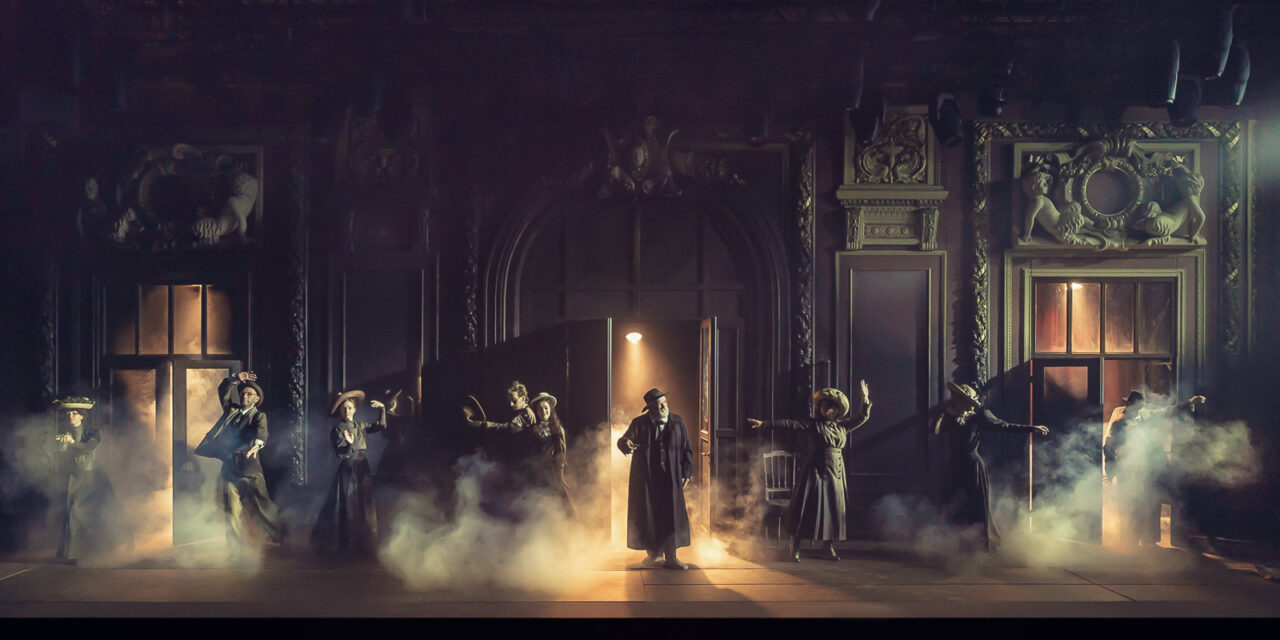

“Everyone Is Here,” dir. Dmitry Krymov at the School of Modern Play in Moscow. Filmed for Stage Russia. Photo by Yury Bogomaz.

Everyone is here . . .

Here, as in a child’s kaleidoscope, many different feelings of the artist are mixed up, penetrating one another firmly, fused to a state of unity. And yet some kind of poignant, childish intonation comes through. Despite the fact that a person who is no longer young is telling this story to us—and the events that occur on the stage are far from always the impression of a child—one cannot escape the feeling of a child’s game, the age of tenderness and innocence.

The naivety of the author-narrator (played by Alexander Ovchinnikov) is so natural and incorruptible that it envelops us from head to toe. The viewer of this performance immediately, on a grand scale, from the first scenes, gets stuck in this children’s memory as in a favorite delicacy.

All the well-known techniques of the Krymov “artist’s theatre”—which, in recent years, by the efforts of the master himself and his students, have stood out as if in a separate theatrical dimension, in an independent genre—work here like clockwork. These include funny little touches like water squirters from which tears are shed, or a khachapuri (a Georgian bread) moving on an impromptu fabric “table,” or toy cars rolling around the stage, the hero rushing between them as he tries to cross a Moscow street in 1973 . . . but also global spatial solutions built on lighting accents and the use of the very body of the theatre building, the School of Modern Play.

All this causes the joy of recognition, understanding, involvement in the artist’s thoughts. Each image is multivalued; it transforms in time and space and gives rise to new insights, meanings, metaphors. Some of them are so strong that a lump in the throat does not go away for several minutes after a scene is over.

For example, a scene with a fake leg, which the hero swings, explaining that he has one leg “there”—that is, at that time, in those events. There is a wonderful figure of speech in Russian, “one foot here—the other there,” meaning that a person will return from a trip very quickly. In Everyone Is Here even this well-known phrase acquires a dual meaning. “I have one foot THERE” says the hero, and the viewer hears: for the author, what is HERE is just a part of life, and far from the fact that it is significant.

Then this sham leg ends up in the hands of the hero’s mother. Some kind of magical music sounds, instantly evoking black-and-white Moscow from films past . . .and the mother-girl Natalia Krymova begins to play with this fake leg. She first takes shelter from the rain under it, like under an umbrella, and when the rain stops, she starts dancing around the stage. And at first this leg is used as a cane-umbrella, easily, gracefully, evoking Fred Astaire, but step by step, the actress gradually dries up, hunches over, and turns into an old woman leaning on this leg of her son, thrown into the past, like a wand.

Lord, it becomes difficult to breathe from the pain and beauty of this image. All these breathtaking visual solutions can be listed seemingly endlessly and admired nonstop.

But despite the abundance of vivid artistic images, they do not merge into a common emotional background, but are, instead, each remembered separately, as if the director found a way to sort each picture according to the right shelves in the heart of the viewer.

I remember everything. From the black cat that starts the show peeking out of the door with impudence and pride inherent only in cats, to white birds fluttering across the stage. Pigeons, by the way, once fluttering out of the door, roam the stage in a businesslike way, clearly disapproving of these shameless bipeds devoid of feathers fussing around. The characters appear from many doors: the wall itself, dotted with these doorways, seems to be an illustration of our memory, in which a draft always slams the shutters.

And then there’s a central door. The hero, talking about his parents for the first time, begins to dismantle the broken glass inserted into these massive doors with his bare hands. Mom and dad appear in the windows, dismantled from fragments. And when their time comes, the time for the parents to leave in life and out of the play, the viewer will see the gaping holes of broken glass in the form of their profiles on closed doors for a long time to come.

Each image is burned into memory. Why is this happening, you ask yourself?

Maybe the whole point is that the author of the performance truly appreciates his memories and feelings?

The scenography of Everyone Is Here is concise and precise. The image of memory is visible and transparent. Most action takes place on the proscenium, with the artists as close as possible to the viewer. Sometimes the characters even invade the auditorium, because it is unrealistic to stay on a narrow strip of stage space if your emotions are whipping over the edge, and there are more than enough emotions here. This feature of the performance reaches its peak in the finale, when all the characters are literally on the verge of death.

Memory often betrays us; memory is always a boundary, a shaky sense of balance. Therefore, everything is brought forward: heroes, events, feelings. At first it may seem that the story is confused, indistinct, too emotional to become some kind of serious theatrical statement, but over time it becomes obvious that there is nothing accidental here. In the events that pop up during these short sketches of life, there is some kind of defenselessness that unites them, as if awkwardness. It’s as if a person who shares important moments of his biography with us is a little shy about frankness and is afraid of being inappropriate or uninteresting.

Therefore, perhaps, the two main emotions that permeate the performance are the fear of not being on time and the feeling of awkwardness. Everyone Is Here is an endless attempt to tell the important, to keep time from slipping through our fingers, to squeeze as much of your love and life as possible into short stage sketches, but . . .

But when life and love are told, played out, indicated by the imperfect means of the theatre—cardboard, fake mustaches, papier-mâché—one gets the feeling that all this begins to seem superfluous or false, unnecessary, inappropriate to the narrator himself/

Then there is another refrain of the play, “Well, something like that . . . Something like that . . .”

Over and over again, after the next memory and his stage incarnation, the hero-Krymov condemns: “Something like this . . .”

Do you understand? That is, all this is approximate, not as it should be, everything is a little inaccurate, damn it! Not that! It is impossible to convey what the memory has preserved, to explain, to convey “from soul to soul” as Konstantin Stanislavski tried in vain . . .

But at least this way . . . Something like this . . . Well, something like this . . .

Because you still have to try to say and do. In order to at least roughly make strangers in the hall understand and feel what does not allow you to live, sleep, and breathe in peace.

“Empty, empty, empty . . . Scary, scary scary . . .”

And it is impossible to explain, and it is impossible to remain silent. The eternal dilemma of the artist.

There is a common truth that any performance is a director’s diagnosis. To understand what kind of person creates this or that theatrical reality, you do not need an interview and a biography on Wikipedia. It is enough just to see what and how he does on stage or in the cinema.

The artist reveals himself to the maximum in his work.

Krymov, of course, is no exception. For several decades we have been seeing his inner world, phantasmagoric, inventive, bright, and surprisingly deep. And each of his performances is a new facet, a new refraction of this universe called “the worlds of Dimitry Krymov.”

But, perhaps, we have not seen the director so defenseless and vulnerable before. So candid. So . . . self-sufficient.

Undoubtedly, the artists of the School of Modern Play are beautiful, accurate, and professional, and, led by the brilliant Alexander Feklistov, they form a powerful choir that sounds clear and distinct.

And on the stage, as in the Greek theatre of the great innovator Thespides, the director and his actress are engaged in an endless dialogue. There is a feeling that everything else—people on stage, animals, props—only help these two to understand the intricacies of their emotions. And this is such a personal story of one person about two heads that at times it seems just an excuse to talk about something important only for them.

The duet of Dmitry Krymov and Maria Smolnikova creates the semantic and sensual core of the whole action. It seems that these two know something special about time, about art, about inspiration. At one time, Anatoly Efros also deeply and touchingly collaborated with the great Olga Yakovleva, and this also has a kind of continuity.

Probably, in any other performance, such centralization of the figures of the director and his actress would be a negative and would cause embarrassment, but not in this case. In Everyone Is Here every scene hits the bull’s-eye, so much so that Robin Hood would be envious. Krymov is Krymov because he can make his deep, almost intimate experience so visible and direct that it becomes important and even necessary for everyone in the audience.

The fact that the management of the School of Modern Play, and personally Iosif Reichelgauz, dared to give Dmitry Krymov absolute carte blanche for a deeply personal story demands respect. Who else on the theatrical map of Moscow would have agreed to give a director, even such a well-known one, the opportunity to tell about himself and his loved ones, without defending himself with some big name like Shakespeare or Ostrovsky? Who would be willing to risk box-office success when the average viewer often goes for the catchy name of a playwright? Who would think of giving the director an excellent troupe but allowing it to be more of an entourage, and allowing a guest actress to play a central role?

Nevertheless, here it is—a performance that violates all the mercantile and cynical laws of our time. It is all the more wonderful that absolutely deserved success came to the performance, and to the theatre, and to the troupe. In the end, everyone involved was a winner. And you know what? For me, there is nothing more joyful than witnessing creative justice with my own eyes. When the real and alive is appreciated not only by professionals and aesthetes, but also by a simple spectator. Because love and beauty are concepts beyond framework and conventions.

Taking as a basis his youthful shock from seeing Thornston Wilder’s Our Town performed by the Arena Stage company, Krymov unfolds his memory like a canvas in width and depth. The director goes for a cool and nontrivial move: he introduces himself into the play as the main character, in a stunning performance by Alexander Ovchinnikov.

This character’s words are the direct speech of Krymov, a story about his memories, his experiences. The first-person monologue and Ovchinnikov create the image of the director, without falling into parody or excessive reverence. At a certain point in the performance, you simply stop separating the actor from his character. Hero-Krymov on the stage is absolutely alive, natural, the ideal stage alter ego of the author of the play. The text is so appropriated by the performer that at moments the real Krymov, a symbolic and household figure in the Russian theatre, falls out of memory, and only the hero of the performance remains. It is this creation of a theatrical reality in which the laws of our reality are canceled that is the real miracle. And how inspiring that this miracle is being created by an artist before our eyes. Of course, he is not alone in his efforts, and the whole performance forms a kind of “memory pool,” but nevertheless, it is Alexander Ovchinnikov who is the point, focus, and voice of the author of the performance.

The artist manages not only to create a wonderful, memorable image, but to perfectly build the composition, the dynamics of his character. If at the beginning of the performance, this is a slightly insecure person, straying, doubting, then closer to the final scenes, he becomes implacable, passionate to the point of trembling, not tolerating objections. The less time he has for a story, the closer we are to the finale, and the more acutely he reacts to those around him. As if he is afraid of not having time to finish the game, to convey something important, to finish the words that are torn from somewhere inside.

The hustle and bustle from the audience to the stage seems nonstop; the artist is in constant emotional tension, a deep inner asset, never weakening the movement of the action, but spurring it on, fully taking charge of everything that happens. And the further we move with the hero deep into his memory, the more despair and pain grow, and the more we sense that something important has been left unstated.

Ovchinnikov feels the rhythmic pattern of his role; he “cares” so much that you involuntarily lean forward in order to hear better, see more, more precisely understand what the director of the play is trying to convey to us so passionately, but it seems unsuccessful and in vain. Something important is missing, and the hero feels it . . .

Something like that . . . Well, something like that . . .

Three times after the prologue, which presents the play Our Town, which lives in the memory of the hero, the artists enter the stage, playing under the direction of the Stage Manager of Wildler’s play. And three times the insufferable hero-Krymov intervenes in the measured course of the rehearsed production. At first, he politely, if almost passionately, begs to play a scene from the second act instead of starting from the outset. The Stage Manager agrees, not without uncertainty, but where should he go, as he is simply a product of the hero’s memory. Having intervened in the course of the performance for the second time, Krymov is already more insistent, he already demands to play the wedding scene. And from whom? He demands this from Georgian artists, hot-blooded highlanders! They all agree to do so for this strange man running on to the stage. But it’s still not enough. Feeling his helplessness and defenselessness, the hero, Ovchinnikov, shouts, “Help me finish it all! Play us something from Wilder!”

And a poignant, infinitely sad cemetery scene appears . . .

The performance is so perfect compositionally that even with great effort it is difficult to find fault with something. Many episodes that seem random or seem to arise for no reason, without internal justification, later fall into a single coherent picture, like pieces of a puzzle. In general, the performance resembles this puzzle. At first, you have a lot of colorful pieces, but gradually, step by step, a picture of the world appears in front of you. And all the fragments are perfectly fitted to one another.

Judge for yourself. The arc of the play is Our Town. The artists take turns playing, getting to know the world, growing up, getting married, and dying. Between these reference points, the main events in the life of an ordinary person, there are episodes from the life of a specific person—Dmitry Krymov. Events connected with the legacy of his great parents, the death of this legacy in the person of its keeper Nonna Skegina, the childhood of Dmitry himself, his entourage, his grandparents, harsh and not very happy people, and finally his own creative legacy, arising here and now and also doomed into oblivion, personified by an episode of a performance that never happened.

It is almost architecture, but extremely alive and human.

This article continues in part 2.

Alexander Barkar, born in the city of Lugansk, Ukraine, and now based in Moscow, is a theatre director, staging performances in and around Russia. He regularly writes on theater, both personally and professionally, to hone his skill.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Barkar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.