This is part 2 of a piece on Dmitry Krymov’s Everyone Is Here. For part 1, click here.

Along with the amazing Alexander Ovchinnikov, another Alexander, Feklistov, is absolutely beautiful on stage. He plays the role of the Stage Manager from Our Town and for the hero, the narrator of this story, he really becomes his main assistant. Feklistov creates the very structure of the performance, like a rhythm section or a bass part in an ensemble. He is the basis of the action; his significance and some kind of inclusiveness determine the pulse of the performance. He always appears at the right moment to support the director, to make further action possible. Feklistov surprises with his diversity and nuance even in such a seemingly monolithic role. He tells the story of an American or Georgian town globally, powerfully, with passion, with inspiration, leads the action, creating a small acting masterpiece from each of his episodes.

One need only only one tiny detail. At one moment, the Stage Manager, who has climbed onto an impromptu pedestal, is given a microphone, somehow taped to a cane. For some time Feklistov broadcasts into it, but at one moment he can’t stand it and tears the microphone off this “stand.” The tape sticks to his fingers, and the artist, as if not finding anything better, annoyed, sticks it on the shoulder of the artist standing next to him. Detail? A trifle? Yes, but how sweet, subtle, funny, and very human.

In general, Feklistov closely follows the hero-Krymov. In his eyes you can read endless sympathy for this man. He is ready to support, to pick him up, because he feels the real pain and honesty of the narrator. The Stage Manager will do everything to ensure that the performance takes place exactly the way the creator intended it. And not for duty, but for love.

It is impossible not to mention Kirill Snegirev and Olga Grudyaeva—a wonderful young couple from Our Town—who seem to live their lives in a dotted way, but at the same time fully and subtly. Kirill’s character is a delightful klutz, awkward and touching. Not understanding what to do with his life, but warm, not indifferent. And Olga is absolutely a match for her stage partner. She masters a variety of genre colors, brightly and fully embodying the Georgian clown bride on the stage, as well as the difficult tragic afterlife scene in the finale of the performance.

No less bright are Tatyana Tsirenina and Pavel Drozdov, who play the hero’s mother and father. They have no text, but there is so much meaning in their wordless etudes-sketches. Perhaps the highest aerobatics for an artist is to play without words what cannot be expressed in words. Pavel and Tatyana succeed in this “Nesterov’s loop,” the impossible aerobatic trick. They are beautiful and young, like all parents who live in the memory of any adult child from a happy family. Their appearances and departures, smiles and reactions, make you remember your childhood, your loved ones.

But I repeat, no matter how wonderful the artists of the School of Modern Play are, the role of the first violin, the most important and reigning in this Krymovian music, is assigned to Maria Smolnikova.

The fact that Smolnikova has become one of the most significant actresses in Russia of our time, probably no one can dispute. She is not afraid to be funny and ugly, she is not shy about any of the most insane challenges thrown to her by the director’s task. Each of her roles turns into a kind of parade of courage and talent. Her heroines are able to speak in such a way that the viewer can hiccup with laughter, and a second later cry from pain and pity. What she does in the play Everyone Is Here seems like magic, a sacrament. It is an amazing and rare feeling when you forget about hundreds of performances, about thousands of actors, about a million roles you’ve seen before . . . You forget. Because now there is only her on the stage. You are ten years old again, and the theatre seems miraculously incomprehensible and beautiful. You look at the stage, your heart is pounding, and tears are flowing, and you can’t even understand how the actress did this to you. The magic of talent is the whole story.

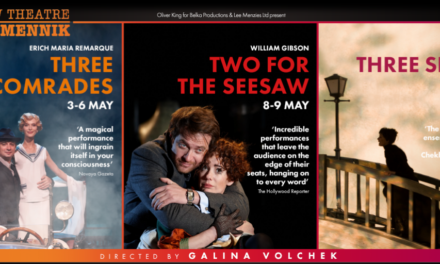

“Everyone Is Here,” dir. Dmitry Krymov at the School of Modern Play in Moscow. Filmed for Stage Russia. Photo by Yury Bogomaz.

In the performance, Smolnikova plays several roles, of varying degrees of significance, but it is worth stopping at two.

The first is Nonna Mikhailovna Skegina, longtime artistic manager for the great Russian director Anatoly Efros, father of Dmitry Krymov. In a sparkling, shiny jacket that is clearly too big for her, holding a microphone with a trembling hand, she speaks in a cracked voice, stubbornly and persistently telling fragments of Anatoly Vasilyevich’s creative biography. With this speech-lecture, Nonna Mikhailovna seems to rebel against injustice and shameful oblivion. She makes you listen to yourself, speaks with passion, uncompromisingly, furiously. She protects her director from the enemies of his art, past and present, from those who have long died and have no power and significance, from those who dared to forget about Efros today.

The actress plays, it would seem, a comic old woman, and the audience roars with laughter at her intemperance, her intelligent swearing, her desire to constantly be wedged into the play with her memories of Efros. At one point, the hero-narrator begins to put fake candles on the chair and asks Nonna to help him. When she realizes that the candles are not real, she hurls an annoyed remark at him: “Your father was looking for the truth, and you are doing your fucking plastic!”

And this remark, better than any melodramatic memories, shows in the mind of the viewer simultaneously the image of Efros, of Krymov, and of Nonna Mikhailovna herself—a real fighter, an irreconcilable gladiator of the work of her chosen theatre and director. When an actress manages to play both comedy and drama with one line, it leaves a deep impression.

And then the time comes for her death, and Nonna Skegina asks that her ashes be spread over the grave of Anatoly Vasilyevich. In her last words to the hero—“Don’t tell me anything now. Just do it”—there is so much power and significance that there is no doubt he will. Because this woman cannot be disobeyed. Because there is too much truth and love in it, without which life itself cannot exist.

Smolnikova in this scene is hypnotic, imperious, infinitely demanding and touching. Don’t break away. I don’t want to let go. Lump in the throat.

And when the narrator begins to talk about how he fulfilled the wishes of Nonna Mikhailovna, Smolnikova, standing a little in the background, begins to pull off her shiny jacket like a second skin, slowly, reluctantly, parting with this amazing woman, whom she gave stage life for a while. Through this, she doesn’t take her eyes off the urn with the ashes, which Krymov tries in vain to open in the cemetery.

Toward the end of the performance, the hero-narrator suddenly recalls a performance that never happened within the walls of the School of Dramatic Art, the theatre that for many years was the home of Krymov and his Workshop. The performance was supposed to tell the story of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov in his own words. In Their Own Words was the title of Dmitry Anatolyevich’s cycle of performances about great writers and playwrights.

The performance about Chekhov never took place, Krymov left the School of Dramatic Art, but one scene from that performance survived . . .

At one time, Anton Pavlovich suddenly abandoned everything and left for the remote island of Sakhalin, where he lived for several months. He met with people, was engaged in the census of the population. Land of exiles, harsh climate, difficult fate . . .

Krymov decides to ask himself (and puzzle the audience with) a question: What happened there with Chekhov, already known at that moment as a prose writer, the author of many successful stories, so that upon his return from a trip to Sakhalin he would start writing plays? The same plays that put the author all over the world, on par with Shakespeare and Molière. What happened to him there? What?

And now the viewer is offered a completely wonderful, hooligan assumption. A “magic if,” as Stanislavsky said. A fantasy, a joke, an instant play of the imagination, and that’s it . . .

During the trip to Sakhalin, Chekhov meets the famous Russian criminal and swindler Sonya the Golden Hand.

Yes, of course, there was no such meeting (probably?). All this is just a wonderful theatrical fiction, but if you imagine . . . then the magic begins.

On the stage is a simple rough table. On one side of the table sits a lanky figure almost three meters tall—Chekhov. A hat, round ribs . . . A long black coat that hides two performers, one on top of the other. A caricature and recognizable image known from our schoolbooks. Throughout the scene he remains silent, listens, and reacts, only a couple of times saying a few awkward remarks . . .

Maria Smolnikova enters the stage, rattling with a long rusty chain, in the role of Sofya Ivanovna Blufshtein—the Robin Hood–like con artist Sonya the Golden Hand. Then it seems that the entire performance Everyone Is Here was made only for the sake of this fifteen-minute scene. Of course, this is not at all true, but the scene is so incredible that for a long time after it, you feel shell-shocked.

Sonya has been in hard labor for a great while. All her brilliant criminal cases are long past. She is chained and shackled to a working wheelbarrow to prevent another escape. She is dressed in an old padded jacket, the usual clothing of Russian convicts. Her hair is disheveled. Half of her teeth are missing.

Smolnikova in the role of Sonya is transcendent. She speak in thieves’ jargon, whole runs of which are cleverly woven into the text of “high art,” does Edith Piaf singing “Accordionist,” painfully becoming like the Parisian “Sparrow,” she kisses the dumbfounded Anton. The actress is so contagious and organic in any of her manifestations that words do not convey her skill. Words are powerless. How to describe a miracle? How to document magic?

Probably the closest comparison would be this: Smolnikova in this scene is a shaman who has fallen into a mystical trance. Spirits speak through her; her body is a conductor of truth.

Sonya talks about her life, and familiar words suddenly begin to appear. Chekhov listens attentively and takes notes after her. At first it seems coincidental, but the more she goes on, the more the heroes of future Chekhov’s plays resound in Sofya Ivanovna’s voice. The words of Nina and Kostya, Dorn and Arkadina, Trigorin and Tuzenbakh, the three sisters and God knows who else will appear in the story of the experienced swindler . . . All of them are cut through in the words of this old, half-mad woman, they will all soon grow into heroes of great drama, because without theatre it is impossible.

All of them are here.

All here . . .

At some point, the effect of mixing the funny and the tragic becomes absolute. The words of the old convict, the words of Chekhov’s plays, strike without pity and without sentiment. Suffering, love, faith in the best, and the desire to change everything are woven into a tight ball embodied in a small woman of some incredible strength and significance. Before us appears the image of a great dramatic actress, a ruined talent, a victim of the eternal uselessness of the prophet in his own country. Here are Akhmatova’s “If you could know what gibberish empowers” and Chekhov’s “one must live, one must live . . .” and the eternal Russian “ability to endure.” All here.

Chekhov listens, and the viewer becomes witness to the birth of the great playwright. And it is impossible to cancel this feeling of participation in the emergence of what will become eternal and immortal.

Everyone Is Here gives us a unique opportunity to feel what happens to the artist at the moment of inspiration. To participate in the creation of a masterpiece. To feel the real pain, horror, and despair of a stranger and accept them as your own. To be filled with feelings that will guide Chekhov’s hand during the creation of plays familiar to theatre people to the last comma. Is this scene funny? Yes! Homeric! Does it cause high empathy, and not vulgar pity? Yes! Undoubtedly! And this dual feeling does not let you go for a long time, holds you tenaciously with the grip of a bull terrier and does not give you rest.

The story of Sonya flies by almost instantly, although it seems like a full-fledged performance. I want to prolong this delightful torture indefinitely, not let go; I want to see this unfulfilled Chekhov in His Own Words now, urgently! And it seems the greatest injustice that only one scene is left of it. But how wonderful that the idea of a piece of a performance that didn’t happen is so exactly parallel to the failed career of the great Russian actress Sofya Blufshtein.

“Oh, if only I knew, if only I knew…”

I have watched this episode in the recording some countless number of times.

But perhaps the most important moment for understanding the performance sounds at the end of this strange dialogue with the silent author of The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard. When Maria-Sonya climbs onto the table and, directly in the eyes of her lanky interlocutor, says “and your plays will be even better. The plays that you write. We will write,” and it becomes . . .

So . . .

Important.

Because Sonya is now taking a promise, an oath of allegiance to art. An oath that every true author takes at some point in his life. The one who makes it will not be able to calm down, will not be able to turn off the path, will never stop. It’s like a brand.

The author of the performance knows this thirst, which cannot be quenched by anything. It is this phantom promise, like a promise to dispel the ashes, that is poured over the director’s grave, drives him forward, makes him create his own worlds. Not from pressure, not by violence, but by an endless desire to share the beauty, love, and pain that haunt the artist’s soul.

God knows where and when Krymov met his Sofya Blufshtein, but now, apparently, he has no right to remain silent. Even though Maria-Sonya tells him, when leaving, “by the way, you cannot mention my name on the cover,” the oath from this does not become less significant.

So it turns out that over and over again you put on performances, write music or poetry, draw or sing, because you simply do not have the right to betray your Sofya Ivanovna or Nonna Mikhailovna. Because she will get from the last world.

And also, because without the theatre it is impossible.

And because everyone is here.

“Everyone Is Here,” dir. Dmitry Krymov at the School of Modern Play in Moscow. Filmed for Stage Russia. Photo by Yury Bogomaz.

I didn’t get to watch Everyone Is Here live, although I heard from my beautiful wife that this performance was the strongest impression of this theatrical season.

I am sincerely grateful to Stage Russia for offering me the opportunity to watch their film of this performance. They read a post I wrote about Yury Butusov’s latest work, R, and for some reason decided that I would be able to appreciate the merits of their video version of Everyone Is Here, which is being prepared for cinema distribution in England and the United States.

I tried my best to convey my thoughts and emotions. I hope something worked out.

The camera work, color correction, and video sound are beyond praise. It’s no secret that few people prefer to watch performances on video, but with Stage Russia’s Everyone Is Here I did not have any problems or discomfort. The angles are chosen well, in my opinion; the performance looks like a single work, and the effect of being there is deeply felt.

Of course, Muscovites have the opportunity to watch this new experience of Dmitry Krymov live, and I sincerely recommend that they run headlong for tickets. But for those who are across the seas and oceans, I strongly advise you to wait for the official release of Everyone Is Here in cinemas. An amazing performance in a highly professional film version . . . Believe me, it’s worth it.

“Everyone Is Here,” dir. Dmitry Krymov at the School of Modern Play in Moscow. Filmed for Stage Russia. Photo by Yury Bogomaz.

Instead of an epilogue.

This is, ultimately, the performance of a cosmically lonely person. He really has one foot “out there.” He understands that when his life path ends, all this beauty, all these feelings, these beautiful people, all the amazing visual images will die with him. And while still alive, he mourns this beauty by sharing it with us.

All these people, all this—in his memory.

The memory becomes a cemetery, and there is no hope for continuation, no new life in the play. Because the urn with the ashes, the truth that his father was looking for, the performance of Mikhail Tumanishvili (the “Soviet Rambo”) . . . they are all here. In the head of the director. In his memory. In his private cemetery.

And nowhere else.

He makes us laugh by mourning the personal. He makes us cry by laughing at himself.

From the very beginning of the performance, from the first scenes, the viewer feels this poignant intonation of sad clowning. So what? Everyone is here? All this beauty and love, all this life so passionately and so touchingly told, will die with the person who keeps it? Disappear without a trace?

No.

Because I will never, before my death, erase from my memory the meeting of Chekhov and Sonya the Golden Hand, the cemetery of Our Town, the funeral of Nonna Mikhailovna, the fake leg.

I will not forget how sitting at the computer screen, in front of a cold, plastic, twenty-one-inch Phillips monitor, I was shaking with sobs and could not calm down.

And I will tell about this performance to anyone I can, as best I can, because the living do not die.

They grow again.

Alexander Barkar, born in the city of Lugansk, Ukraine, and now based in Moscow, is a theatre director, staging performances in and around Russia. He regularly writes on theater, both personally and professionally, to hone his skill.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Barkar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.