Homegrown: Occupy Festival

Battersea Arts Centre

March 18 – April 12

Lakeisha Lynch Stevens in High Rise eState Of Mind by Conrad Murray and Beats and Elements

When it comes to arts venues, Battersea Arts Centre is certainly a performance space with a difference. Not only is this former Town Hall adorned with unique architectural features (bee mosaics, a bespoke music organ built into its architecture) and extraordinary stories of survival (recent miraculous ascent from the ashes, following a big fire of 2015) – but it is the closest a cultural center could ever come to feeling like a home.

The secret of this homely feeling is partly rooted in its approach to programming which values community-building events as much as regularly produced work. The past few weeks have seen A Grand Night Out event in which playwright Simon Stephens interviewed footballer Gary Linekar and Tourettes-hero star Jess Thom interviewed Channel 4 Broadcaster Jon Snow, followed by a whole day of screenings of films about theatre made in collaboration with the BBC. My highlights from what I caught of the latter include a documentary about the making of Beckett’s Not I by the above mentioned neuro-diverse performer Jess Thom, commissioned by BAC in 2017, and Hofesh Shechter’s mesmeric dance contemplation on “how far we will go in the name of entertainment” -Clowns.

The latest offering from BAC is a month-long Homegrown festival timed to coincide with the originally planned Brexit-date, and specifically intended to celebrate cultural diversity. Curated by young producer Saad Eddine Said, this year’s edition entitled Occupy opened with a line up of six shows taking place around the building whereby each audience member could see a double-bill on a given evening. I caught Conrad Murray’s new piece A High Rise eState Of Mind and Xavier de Sousa’s Post.

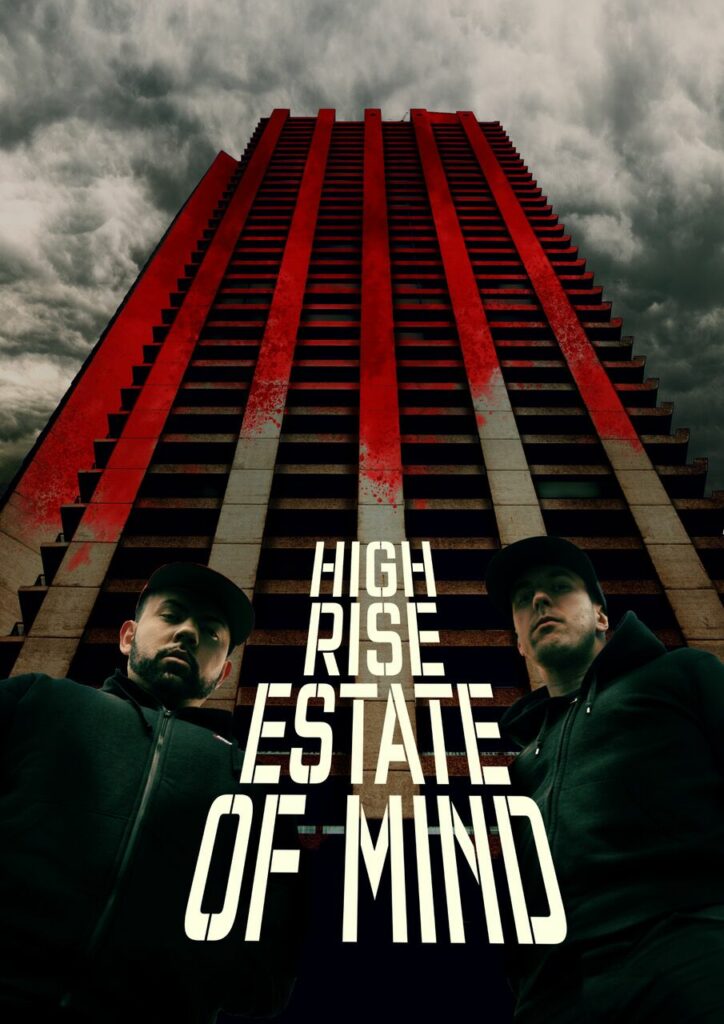

High Rise eState Of Mind by Conrad Murray and Beats and Elements, (L-R Conrad Murray, Gambit Ace Lakeisha Lynch Stevens, Paul Cree)

Murray’s brand new piece of hip hop theatre follows the stellar success of his adaptation of Frankenstein, an ensemble extravaganza created with a group of young people from South East London who meet weekly under Murray’s tutelage at Battersea Arts Centre as members of the Beatbox Academy. A High Rise eState Of Mind is Murray’s collaboration with hip hop artists Lakeisha Lynch Stevens, Paul Cree, and David Bonnick Junior. The piece is directed by Murray, who leads his crew gently from behind by also performing on the stage with them. Meanwhile, the writing credit is given to Beats and Elements – that is, the company as a whole. Narratively speaking, it is a complex piece – an intertwining of a dystopian story of high rise estate city living, which also functions as a horror allegory for the British class society, and of the personal stories of the performers themselves. There is also a moment in which an audience member’s dreams will be woven into the fabric of the piece by the freestyling magic of David Bonnick Junior. Somewhat surprisingly, these spoken word artists turn out to be excellent character actors too and even an acoustic guitar makes a notable appearance within its regimented choreography. In the best tradition of storytelling and community-building, this is a true feast of talent, candor, humor, wisdom, imagination, empathy, and the delicious fruits of dedicated creative practice, that will have you leaving the theatre both touched and elevated.

High Rise eState Of Mind by Conrad Murray and Beats and Elements, (L-R Conrad Murray, Paul Cree)

At the other end of the building, Portuguese Xavier de Sousa is cooking a soup. He has a set consisting of some domestic furniture and a carefully chosen frame hanging on an invisible wall into which a projector casts relevant text and images, as the show progresses.

As the audience trickles in, De Sousa, wearing a faux-ethnic hat and a skirt, is chatting in a totally open, genuinely interested and relaxed manner to those already in their seats. He wants to know where individual audience members come from, what they do, who they are, but he makes it feel like these things matter far less than just having an easy conversation. Then he asks how much hosting is important to any of us; and how we would rate him on his hosting at this moment in time on a scale from 1 to 10.

De Sousa’s show could be seen as having two halves: one in which he sets the scene by chatting to us/casting his guests, cooking and telling us stories (about himself, about his native Portugal, the histories of its migrations), and the second in which he holds the space for four other people to tell stories and answer specific questions around his dinner table. Mostly thanks to his extraordinary curatorial facility, this transition is seamless – and sweetened by the serving of an aperitif to everyone in the audience. He deftly even clones himself by selecting an audience member early on and gradually priming him (on this occasion another Portuguese man) to eventually take his place at the table as the host-double, so he, the ultimate host, can step out and continue to look after the show from the outside (notching up a glowing 10/10 for hosting by the end).

The inner structure of the piece is a kind of automaton, consisting of a series of questions which the four diners selected from the audience will proceed to take out of the envelope (and which are also projected on the wall for our convenience) in the course of the party – through the duration of the piece is very much dependent on the garrulousness of the guests and, potentially, the extent of their inebriation.

At this point, I am compelled to offer a personal disclosure that, like de Sousa, I too am culturally and personally deeply invested in the question of hospitality. Like de Sousa, I too am also a guest in the UK, the country I have lived in for more than half of my life. I didn’t happen to be asked any questions and I didn’t feel free to volunteer – and although I’m sure it would be a welcome relief for many potential audience members to know that they are not obliged to participate in this potentially highly participatory show – I found myself experiencing the opposite problem on this occasion. From the moment the topic of hospitality came up I was desperate to be involved in this conversation. What is more, within the first few minutes of de Sousa’s performance starting, it was becoming clear to me that this was indeed the very show that I had been unconsciously making and rehearsing myself for years around my own dinner table, hosting dinner party after dinner party with strangers, acquaintances, and friends on endless Saturday nights in my various temporary homes over the decades of my life in England. I am not really a foodie or even a particularly good cook, but what I have always loved about these occasions has been the facilitation of sharing of the personal stories, the cultivation of connection, the search for a sense of belonging.

POST by Xavier de Sousa at Battersea Arts Centre as part of Homegrown Festival Occupy

As it happens the element of frustration I had to grapple with around my own non-participation was not necessarily unique to me. I am sure many were also secretly fantasizing about being at the table for other reasons – maybe the tasting of the brandy-cooked chorizo or the sparkly wine, or a particular question being aired (“When moving to a new place is the onus on you or the others for you to fit in?) – but this feeling of being left out, was also possibly thematically quite relevant and dramaturgically integral to the show which ends up reflecting in a beautiful piece of prose by de Sousa on the notions of community itself.

POST by Xavier de Sousa at Battersea Arts Centre as part of Homegrown Festival Occupy

De Sousa’s show is subtle and sensitive (and so beautifully lit!) at all the right moments. But above all it is clever. And timely. It should be licensed as a format, or built as a compulsory element into the British citizenship ceremony. It is a show that everyone in the UK should have done in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. And it is also a show for which, the more I think about it, de Sousa’s hosting score is going through the roof like that number of signatories on the second referendum petition. And ultimately it is a show that, not unlike Murray’s, puts “home” at the heart of the Homegrown festival at BAC.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.