The official stats have it that in its 73rd year of existence, the Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2019 will have hosted 3841 shows in 232 venues across the city. It’s hard enough choosing what to see even if you’re here for the whole four weeks of August, but if, like most punters, you happen to be visiting for just a few days, your selection might be exceedingly a niche.

Embarking on a research project on aural dramaturgies in 2020, I have selected to focus my three days in Edinburgh this year specifically on the form known as gig theatre.

What is gig theatre? How has it come about? How do you tell it apart from the much longer-running and better-known forms of musical and cabaret? And is it specifically British, or does it exist in other cultures too?

My research so far reveals that the first recorded – though quickly forgotten – use of the term ‘gig theatre’ appears in the Irish press, and is attributed to actor/writer Donal O’Kelly as a description of his piece The Hand presented at the Dublin Festival 2002. In the run-up to it, Brian Lavery of the Irish Independent wrote: ‘The Hand is a debut presentation of O’Kelly’s idea of gig theatre, a concept that, if it works, will eliminate the boring parts of regular drama, will forge a more open, honest bond between the actors and the audience, and will do it through music.’ Gig theatre, however, did not seem to work out at the time. Luke Clancy of the Evening Herald (Dublin) determined that: ‘The mood of the evening lands – sometimes uncomfortably – between Under Milk Wood and Tom Waits in one of his fistfight-in-the-junkyard phases’, while Fintan O’Toole of The Irish Times, was equally unimpressed, finding the concert-like presentation disruptive and the addition of a jazzy score to O’Kelly’s already musical writing, ‘excessive’ and ‘almost formulaic’. Perhaps O’Kelly was ahead of his time, or maybe the Dublin Festival was the wrong context for his innovation, however, something symptomatic does emerge out of this example. Gig theatre, especially in its more contemporary manifestation, does seem to be contextually linked to festivals, and most notably, in the UK, Edinburgh Fringe and Latitude Festival.

Cora Bissett’s What Girls Are Made Of. Press photo

In the run-up to the Edinburgh Fringe 2016, both The Stage and the Skinny ran features on the newly emerged trend, by then commonly referred to as ‘gig theatre’. Holly Williams in The Stage listed a number of previous Edinburgh hits as defining of it: Kieran Hurley’s Beats (2012), Lucy Ellinson, Chris Thorpe and Steve Lawson’s Torycore (2013), Brigitte Aphrodite’s My Beautiful Black Dog and Middle Child’s Weekend Rockstars (both 2015). She also acknowledged the significance of Latitude Festival whose dedicated theatre stage became a ‘major platform for gig theatre’. It is important to note that Latitude was founded in 2006 by the parent company of Glastonbury and Leeds and Reading Festivals. It was another music festival but with a bit of theatre thrown in, and this particular ecology seems to be an important factor in the inception of the genre.

The few existing journalistic overviews of the genre, based on interviews with relevant artists, crystallize a number of the form’s other significant features: namely, artistic collaboration and transdisciplinarity at the point of inception, the importance of accessibility and a relaxed non-bourgeois code of behaviour at the point of reception, as well as liveness and the associated value of community-building which distinguishes gig theatre from other dominant forms of cultural consumption mostly taking place via screens or mobile phones.

These characteristics are certainly to be found in some of the classic examples of the genre listed above, but possibly nowhere more explicitly so than in Electrolyte by Wildcard Theatre, which I caught up with this year at the Pleasance Courtyard on its return after the sell-out run of 2018. Wildcard Collective was founded by a number of graduates from Oxford Stage School in 2015, and the adrenaline-inducing effect of live music informed even their inaugural production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 2016. They are blessed to have an extraordinary musician/composer/performer Maimuna Memon in their midst as well as a number of gifted writers. Electrolyte is an original verse drama by joint Artistic Director James Meteyard who also has a character part and plays in the onstage band.

The distinguishing feature of gig theatre is that it is made by theatre ensembles whose membership consists of multi-tasking artists, and its key performers are often equally skilled as both musicians and actors, shape-shifting and stepping in and out of each role seamlessly as required. In gig theatre everyone is a star, or as Electrolyte repeatedly claims, ‘we are all made of stardust and dreams.’ Part adventure story, part socially-engaged drama, Electrolyte is a piece about the crucial and redeeming importance of friendship in our lives, especially at the time of increased alienation via digital media. It speaks to audiences in a very direct, powerful and effortlessly inclusive way and, unsurprisingly, it keeps selling out once again.

Another extended run confirming its show’s classic gig theatre status and granting access to those of us who could not get a ticket last year is given to Cora Bissett’s What Girls Are Made Of. Transferring from the Traverse Theatre to Assembly Hall on the Mound, Bissett’s piece is mostly a memoir in a music-theatre form focusing on Bissett’s teenage rock stardom as part of the Fife-based band Darling Heart in the early 1990s. This piece too carries a secret community-building power in its heart but does so on a number of different, often unrelated levels, simultaneously. It speaks to the original fans who remember the music and are back for more, it speaks to the intricacies of being Scottish, it has a deeply touching thematic thread obliquely suggested by its title which is about family heritage and reproduction, it speaks to those who are, like Bissett, in their middle age remembering the post-punk, indie, grunge bands of their youth, and above all it speaks to women and girls of all ages – and to their fathers – whatever their own trials and tribulations, rites of passage and rituals of adulthood might have been. Bissett might at one time have been named ‘a phony record company contrivance’ by NME, but hers is, by all means, a story of triumph over adversity – and packaged into a rock concert, so what more could one want!

Rachael Young’s Nightclubbing. Press photo

Gig theatre is not a matter of rock’n’roll exclusively though. Electrolyte has a techno vibe to it, while hip-hop and grime have also spawned significant examples of the genre, probably most notably in the work of Kate Tempest and the roof-raising Frankenstein by Conrad Murray and Beatbox Academy, currently also on at Traverse Theatre as part of the festival. Another fascinating boundary-pushing experiment is to be found at Summerhall, courtesy of multidisciplinary artist Rachael Young and inspired by the work of Grace Jones. Under the title of Jones’s first album, Nightclubbing, Young’s new work juxtaposes personal experience of access to popular culture as a person of color and Jones’ foundational significance in it. Consequently, the piece is set to the beats of Jones-inspired musical afro-futurism composed and performed live by Mwen and Leisha Thomas. Young fuses together visceral spoken word, striking stage imagery, contemplative performance style, and live music to shine the light on identity politics and when she eventually allows the material to fuse into a couple of full-on gig theatre numbers, she certainly leaves the audience wishing for more.

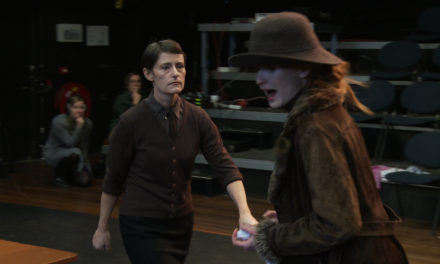

Middle Child’s The Canary and the Crow. Press photo

A similar theme is explored in more narrative terms in Middle Child’s new piece The Canary and the Crow, made in collaboration with writer-performer Daniel Ward and rapper Nigel Taylor (a.k.a Prez 96). This is a semi-autobiographical story told by Ward about his childhood experience as a black working-class boy unable to find a sense of belonging between his estate and the elite boys’ school which he attends on a scholarship. The story is smartly structured as a series of school/life lessons and performed with the help of versatile musician-actors Rachel Barnes, Laurie Jamieson and co-composer Prez 96 himself. Excellent sense of timing in among the ensemble produces exhilarating music, comedy and moments of deeply felt emotion. It is a complete experience in so many ways, not least because the audience is also so much more obviously diverse than ever before at the Edinburgh Fringe. Middle Child and gig theatre’s commitment to accessibility is therefore manifested here in a way so much more honest and believable than was ever the case with any kind of racial inclusion policy tick box exercises of the previous decades, and as the audience members watch each other watch the difficult representation of their own society, being ‘woke’ finally becomes a true shared experience rather than just a trend.

The Canary and the Crow is performed in the Roundabout at Summerhall arts center, a touring tent belonging to the Paines Plough new writing theatre company. This venue has been instrumental in the development and promotion of gig theatre, ever since its first appearance at Edinburgh Summerhall courtyard some five years ago. Its in-the-round set up has landed itself well to the sharing nature of both participatory dramatic works such as Duncan Macmillan and Jonny Donahoe’s Every Brilliant Thing and gig theatre such as With a Little Bit of Luck by Sabrina Mahfouz and Middle Child’s 2017 hit All We Ever Wanted Was Everything.

This year, another one of the gig theatre pioneers, punk poet Brigitte Aphrodite, also has a new show at the Roundabout under the title of Parakeet. Developed with and inspired by her socially engaged theatre work with the young people and refugees in Kent, Parakeet is a piece of colorful idealism rendered through a new kind of punk – ‘punk with empathy’. Finding one’s voice with a help of a gang of exotic birds, saving a tree from being cut even if only for as long as six hours, standing up to authorities of all kinds, Parakeet is an often funny and rousing, poetic and whimsical piece, which also incorporates the voice of Sir David Attenborough into its soundscape, otherwise composed by Aphrodite’s regular collaborator Quiet Boy. Aphrodite and Quiet Boy also perform the score live, and occasionally, Aphrodite steps in to play the piece’s antagonist, a sleazy stepdad. The most watchable and endearing aspect of this gig theatre piece though is the care and love with which the dazzling diva that is Aphrodite tries to blend herself into the background in order to support and watch the younger ones fly.

Defying any generic moulds, gig theatre appears in many variations. As I leave Edinburgh I read about the Maltese show MARA, an electro-acoustic ensemble piece about women through time. It does not call itself gig theatre but its descriptions testify to the raw and angry, rousing and immersive, DIY aesthetic that characterizes this particular art form. Elsewhere in Edinburgh, Tricky Second Album, a piece inspired by KLF’s act of burning one million pounds in 1994, is anti-establishment, anti-theatre, anti-Fringe piece of gig theatre which includes a performer in the eighth month of pregnancy, and has had to be cancelled due to health and safety reasons on at least one occasion. These are some of the other boundary-moving works I will have to try and catch next year if they happen to come back. But if they don’t, I’m pretty sure some other gig theatre will as it certainly feels like a trend that has some more life left in it.

Camille O’Sullivan in Cave.

Finally, a few words about another Irish outlier. This year marks singer Camille O’Sullivan’s fifteenth anniversary at the Edinburgh Fringe where she has been wowing audiences year on year with a pretty regular cabaret repertoire of Weill and Brel and a bit of Piaf peppered with occasional outings into the work of Tom Waits, Nick Cave, and Dillie Keane. This year though she has ditched the iconic velvet, satin and high heels for an all-out Nick Cave tribute act, complete with a black skinny trouser suit and glittery boots. This is not gig theatre nor is it trying to be theatre of any kind – the evening consists of a straightforward succession of musical numbers alone and some regular ad-libbing in between. However, Cave’s songs often do carry the intricate narrative and deep drama in them, and Camille O’Sullivan’s staggering rendition of them certainly unlocks new levels of appreciation for this material. Besides, O’Sullivan’s clear move away from conventional cabaret towards something more explicitly post-punk, and so exquisitely poised between heaven and hell, does seem to point to a larger trend and the spirit of the moment that all these works share.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.