It was a private performance at Theatre Republic, the affordable production and rehearsal space, in Lekki Phase One, established in 2016 by Wole Oguntokun, the theatre heir of Wole Soyinka.

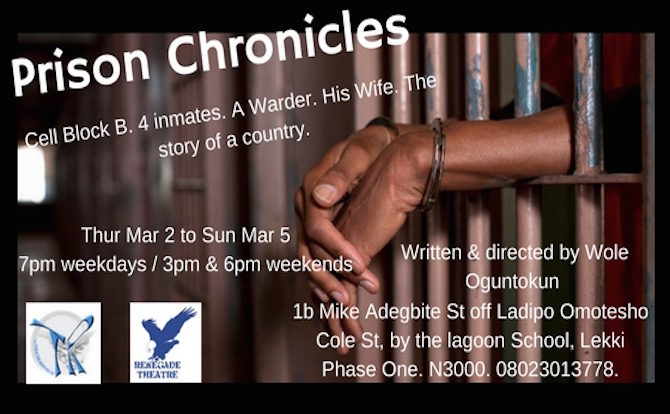

Four prisoners with a sense of gallows humour, a psychotic prison warden, and his conniving wife mirror the play of power, privilege and the politics of our common Nigerian experiences. In the tradition of Soyinka’s Madmen and Specialists and Ken Saro Wiwa’s Prisoners of Jeb, Wole Oguntokun revived his March 2004 premiered play, Prison Chronicles, for an audience of the British Council / International Association of Theatre Critics “Young Critics Programme”; Professor Octavian Saiu, Adjunct Secretary General of IATC and Chair of Conferences, Sibiu International Theatre Festival; Professor Ivan Medenica, Director of Conferences, IATC and Artistic Director/Curator, Belgrade International Theatre Festival; and Professor Femi Osofisan, Nigerian theatre treasure and 2016 winner of the Thalia Prize of the International Association of Theatre Critics. It was an audition for greatness, and both the yam and the knife were in the hands of Oguntokun.

The light goes off and the show begins without warning . . . the subdued song of white-clad prisoners illuminated by a solo floodlight hushes the audience and commands our attention. The traditional Yoruba call-and-answer songs banish boredom from the mundane prison scenes. The psychosis of incarceration, an exhibition of criminal authority, the dialogues of loss and injustice, and the satirical performances of the actors trick the audience into believing in the beauty of poverty, the humour of death and the dignity of hardship.

The sparse stage, the size of a Nigerian prison cell, is furnished with hungry prisoners, empty bowls, dead newspapers, blind faith, mad hope and the hypocrisy of victims. The toilet is a mat-covered bucket . . . less was more than imagined . . . minimalism is the imprisonment of luxury.

Oguntokun and his four law degrees perform the role of the prison warden. His booming voice is out of court and lives on stage. His legal practice, extinguished by his love for drama, the theatrics of language and the law, dies in all who love the arts. The dialogue of his play pays homage to Soyinka; his prolific productions remind us of Soyinka; his name, Wole, testifies of Soyinka . . . and the man can sing and act like his literary father. Does the man die in those who embody other men? Is your voice loud if you echo another voice? What are the boundaries of influence and reincarnation?

The legacies of Oguntokun: his former boys are theatre festival directors; his mentees are now professional colleagues; and his private stage, Theatre Republic, is training ground for the next generation of Nigerian dramatists and theatre practitioners. In these dying days of Nigerian theatre, Wole Oguntokun attracts the patronage of Lagos, and he imprisons our attention.

At the end of his play, the audience is led to a cliff and left wondering whether they have fallen or remain hanging when the lights suddenly come on and the actors take a bow.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Amatesiro Dore.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.